The Performing Arts Archives and Penumbra Theatre are collaborating on an innovative project to ensure performances—and their off-stage settings—live on after the curtain closes.

The story would by now seem apocryphal, if it wasn’t true. Years ago, a Twin Cities performing arts organization began pouring the contents of its file cabinets and closets—correspondence, memos, press materials, even set pieces—out an office window, down a chute and into a dumpster. Someone in the building, horrified at the potential loss of important historical artifacts, rescued the material. Then they phoned the Performing Arts Archives at the University of Minnesota, which gladly accepted the discards.

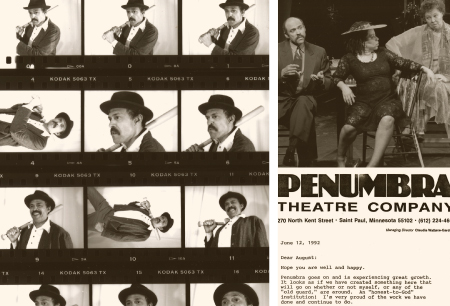

Created in 1971, the Performing Arts Archives accept, organize, preserve, and provide access to the written and audio-visual records of theater, music, and dance companies in the region—before such items reach the dumpster. For many large organizations, such as the Guthrie Theater and Minnesota Orchestra, scheduled deposits of documents and other artifacts occur on a regular basis. But as the aforementioned incident indicates, smaller performing arts organizations often face challenges in recognizing the value of and preserving their inimitable history.

A small staff working with limited resources may not have the time, funding, or even storage space to keep archival materials. They may not realize the value of a letter, rehearsal videotape, or costume rendering to a future scholar looking for insights into the company’s development. Moreover, performing arts organizations are always looking ahead to the next performance, leaving documentation of last season’s creative process on a shelf or in a bin to gather dust.

“Many performing arts organizations don’t begin compiling and safeguarding their archival material until there’s a need for some kind of commemorative event or anniversary,” says Dr. Cecily Marcus, curator of the Performing Arts Archives.

“It’s a problem endemic to the performing arts in general, but the challenges are amplified for companies of color.”

Which is why the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) awarded the Performing Arts Archives a $99,500 grant to work on this problem with the preeminent Penumbra Theatre—one of only three professional African American theaters in the nation to offer a full season of performances. Penumbra and the Archive’s groundbreaking, 12-month planning project, “Preserving the Ephemeral: An Archival Program for Theater and Performing Arts,” will assess interest in and barriers to the preservation of a theater’s full range of activities, with special emphasis on theaters of color and using Penumbra as the case study.

“If this investigation and exploration is successful,” says Chris Widdess, Penumbra’s Managing Director-External Relations, “it will further the archival efforts of all performing arts organizations of color, and allow different voices to be heard, appreciated, and respected.”

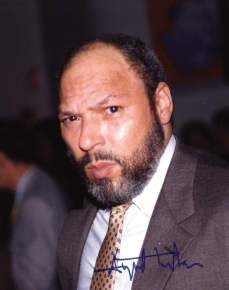

Penumbra has long recognized the value of its heritage. The theater was born out of the Black Arts Movement and founded in 1976 by Lou Bellamy, whom Hoda Kotb called “a legend in the world of American theater” on a recent edition of the television news magazine Rock Center. Bellamy’s goal was to stage the plays of African American writers and portray the lives of African American people.

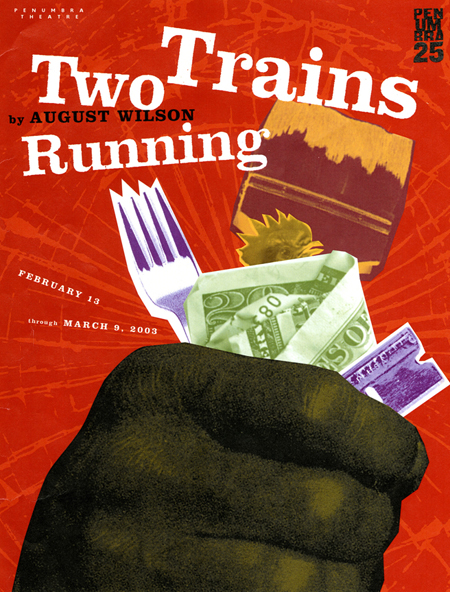

In its 36-year history, Penumbra has become the largest African American theater in the country and has produced 23 world premieres. Many of those were of works by playwright August Wilson, who earned two Pulitzer Prizes for the plays Fences and The Piano Lesson. Penumbra’s archives—including play scripts, performance videos, production notes, and costume renderings—are currently housed in the University Libraries’ Givens Collection of African American Literature.

One day Widdess realized those archival efforts weren’t sufficient. Such material, while important, didn’t represent the depth or breadth of Penumbra’s real work. “Our mission is to stimulate dialogue around issues of racism and social justice from the African American perspective,” she explains. “In addition to staging plays on the African American experience, we surround the performances with community discussions, and written, audio-visual, and web-based educational tools on themes and history.”

“If you go to our archives and look at the plays, there isn’t any material that provides a cultural context for the work,” she continues. “In our current archives, you see the content, but not the context for the content. There isn’t any context for appreciating or understanding what we did and why we did it; for how we activated and articulated our mission through the plays.”

After contacting the Institute of Museum and Library Services about funding a project that would address such contextual issues, Widdess contacted Marcus about collaborating on the Leadership grant. “The Twin Cities is unique in its concentration of performing arts, particularly with theaters of color—of which Penumbra is particularly exemplary,” Marcus says. “But the challenges of building an archive that fully addresses a theater of color’s history isn’t unique to the Twin Cities.”

“So we became interested in talking with other theaters of color around the country confronting the same questions Chris and I have, and developing a system that could be shared,” Marcus continues. “If we could provide resources helpful to performing arts organizations regardless of size or location, that would be valuable.” In addition, the Friends of the Libraries had articulated a desire to focus its energies on the Performing Arts Archives. And Marcus was eager to build upon the archives Penumbra had already accumulated.

Using the framework in place for maintaining the archives of the Minnesota Orchestra, Penumbra and the Performing Arts Archive will work with such regional theaters as the Guthrie, and national partners including the American Theater Archiving Project, Theatre Library Association, and Apollo Theatre Project, to understand the barriers to creating a comprehensive theater archive. The collaborators will also identify processes that can be adapted by theaters of different sizes and configurations, to ensure long-term preservation of and access to their archives.

After the planning year, the collaborators will have devised a national model for a sustainable archival process, including how to locate and acquire scattered records from past productions—materials that costume designers, set designers, or directors often take with them after a production. They will also create a framework for community-based audio-visual preservation and recommend best practices for union contract agreements surrounding the use of performance video recordings.

The innovative proposal was one of 48 selected from 210 applications. “The peer review panel thought highly of the project,” says Robert Horton, Associate Deputy Director of the IMLS Office of Library Services (and formerly library director at the Minnesota Historical Society). “The panel mentioned that the proposal demonstrated a clear need for a set of guidelines, standards, or methodologies to document theater, and that Black Arts Theaters in particular presented a documentary need that hasn’t been met. They also noted that Minnesota has the talent to examine these needs and make recommendations. The end result could well serve as a model for theaters of all sizes and types, and conceivably inform other archiving and documentation projects as well.” Horton adds, “It’s a planning grant, so implementation will be an even bigger challenge. But as the proposal explained, now is the time to get a handle on the variety of formats being used to produce content, from digital to email, and recommend and improve ways to move to more sustainable archiving.”

As Marcus explains, “Every library in the country is struggling to figure out what to do with electronic records. So much correspondence, so many conversations are now happening via email. We’re still encouraging people to print out important emails, but that’s neither practical nor complete. The grant provides us with funding to work on this urgent problem.”

Susannah Engstrom is a Chicago-based scholar who will benefit from the findings of the planning grant. She’s currently doing research in the Performing Arts Archives for her Ph.D. thesis, “The Potentials of Performance: Professionalism and Cultural Democracy in the Twin Cities.” Her research focuses on theater development in the Twin Cities from 1950 to 1975, a time period that encompasses the Black Arts Movement.

“One of the issues I’m looking at is the decentralization of professional theater outside of the New York City,” she says. “The archives provide me with information and insights I couldn’t get anywhere else.” Her research thus far has been focused on the Guthrie Theater. But Engstrom looks forward to examining the origins of Penumbra Theatre, and including the contextual information for which the planning grant provides a archival framework.

The Givens Collection, in which Penumbra’s archives currently reside, “is broader than African American theater and the arts,” explains Widdess. The processes explored and material archived as a result of the planning grant will “allow us to tap into and compliment the existing collection.” Added materials such as study guides, scholarly papers, and other resources will help researchers “understand what Black Americans were dealing with socially and culturally at the time a play was written,” she explains, “or to learn the meaning behind the numerology in Wilson’s Two Trains Running.”

That Penumbra and the Performing Arts Archives could ensure preservation of archival materials for theaters of color around the globe is “a game changer,” according to Widdess. “People of color need to feel proud of who they are and how their identity is reflected in their artistic heritage,” she adds. “A deeper, richer archive will help to make that happen.”

Camille LeFevre is a Twin Cities arts journalist. She teaches arts journalism at the University of Minnesota.