Three denizens of the arts take advantage of materials from the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine to spark their creativity

By Suzy Frisch

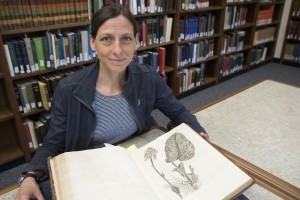

A health sciences library devoted to the history of medicine might not be the first collection that comes to mind for creative pursuits. But in the past year, Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine curator Lois Hendrickson has been pulling items that serve as inspirational fodder for several artists and writers.

From rare books to drawings and documents, the Wangensteen collection of nearly 80,000 volumes from the 15th to 20th centuries fuels their imaginations. Three of these artists share a collective interest in biology and a passion for digging through old material to find just the right image or phrase to influence their creative work.

Here is what they’re reading, viewing, and making thanks to the Wangensteen library.

Ursula Hargens

Ceramic artist and educator at Northern Clay Center in Minneapolis

Ceramic artist Ursula Hargens has always appreciated her medium’s ability to preserve 10,000-year-old history in its very existence. Recently, the role of floral imagery in decoration captured her attention. Hargens started creating work that delves into using floral decorations to address contemporary issues like climate change and invasive species.

Preparing for a show at the Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, Hargens spent many hours in its Andersen Horticultural Library and the Wangensteen. She was most interested in materials that depicted the interaction between humans and plants, and she got enthralled by the collection of old books with vivid illustrations of flora, such as Mary Vaux Walcott’s wildflower watercolors.

Hargens finds many similarities between historic books and ceramics. “With ceramics, you preserve these plants that are endangered in a material that endures. There’s a nice relationships between the fragility of these old books and carefully handling them and ceramics,” she says. “The illustrations also have this luminosity, and we use that word to describe glaze as well. When you see them in person, they are stunning. It was a real treat.”

Hargens obtained a Minnesota State Arts Board grant that supports her fall show, called A Gathering of Flowers: Botanical Art in the Age of Climate Change. She will feature 14 endangered Minnesota plants on ceramic tiles, paired with a reproduction of an image from the Wangensteen and Arboretum libraries.

Jenny Schmid

University associate professor of art and owner of bikini press international in Minneapolis

Jenny Schmid’s fascination with medical illustration and printmaking techniques old and new come together at the Wangensteen, stimulating much of her recent work. Lately she has been poring over anatomical prints from the 1500s and 1600s, intrigued by their form and the function of moving pieces to reveal organs.

“The collection is an amazing resource for looking at etchings and lithographs,” says Schmid, who displays her work nationally and internationally. “The content has been influential for two bodies of work for me that insert new ideas into old printmaking techniques.”

“The collection is an amazing resource for looking at etchings and lithographs.”

—Jenny Schmid

Additionally, Schmid received a University Imagine Fund grant to pursue her Flayed and Displayed printmaking project. She will develop a live animation project of her mezzotints with collaborator Ali Momeni, exploring the artistry and allegory of early anatomical drawings preserved at the Wangensteen while revealing its other medical history treasures.

“There are many images from this era when science was dry and objective. But in terms of the aesthetic of the imagery, there’s a lot of poetry and humor in it,” Schmid says. “I’m responding to the beauty and intensity and the skill of the artist that went into making these displays.”

D. Allen

Artist, poet, and second-year student in the MFA program for creative writing with a visual art minor

Much of D. Allen’s creative writing centers around connections — both biological and interpersonal. So after hearing about the rare medical manuscripts and drawings housed in the Wangensteen, Allen paid a visit and found ample material to power poetry, lyric essays, and a nonfiction research project.

“There is the obvious connection of exploring human relationships that are personal to me across space and time.”

—D. Allen

“There is the obvious connection of exploring human relationships that are personal to me across space and time. One of the most powerful things about using the texts was feeling connected to the people who made the paper and drew the diagrams and set the type, knowing that across several centuries I can still retain a relationship with them,” Allen says. “It’s a powerful reminder of what lasts.”

Allen, who has a connective tissue disorder, also researched the medical histories, descriptive language, and imagery of these diseases. Allen particularly connected with a torso-sized book called Osteographia by 18th century physician William Cheselden and its finely detailed, artful presentation of bones.

Ultimately, the images and language will continually provide inspiration as Allen distills and connects the material to make works of art.

Slideshow of Hargens tile and reference material

Credits

- Floating Marsh-marigold and Purple Loosestrife (Ursula Hargens 2015). Photo by Peter Lee.

- Allioni, Carol (1785). Flora pedemontana: sive enumeratio methodica stirpium indigenarum pedemontii. Plate T.LXVIII.