By Mark Engebretson

When University of Minnesota graduate student Ernesto Razuri had the opportunity to see and interact with 300-year-old entomology books in person, he was a bit awestruck.

“Getting to touch them, it was like, ‘Oh, this is what you get to see in a museum!’ That was really nice,” Razuri said.

The occasion was a mini field trip for Razuri and his classmates in Professor Ralph Holzenthal’s class, Entomology 5051: Scientific Illustration of Insects. It took place last spring in the U’s Natural Resources Library at the suggestion of library staff Shannon Farrell and Amy Gmur.

“We really wanted to get our rare collection out there and used,” said Gmur. “We thought that this collection would work well in Ralph’s class.”

“It’s much better than seeing them online,” Farrell said. “In person, you see the age of the book and you can even smell it. It’s a very tactile experience.”

Learning opportunity for students

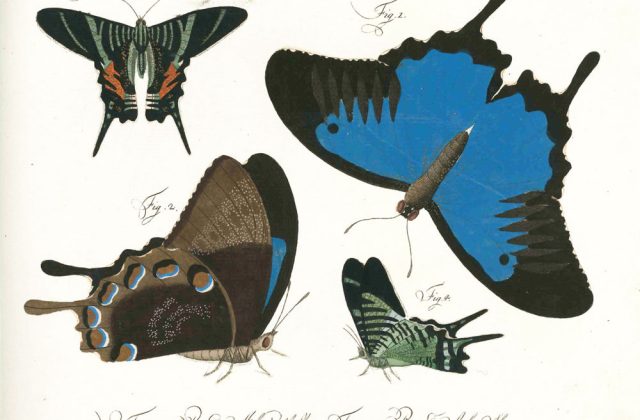

For Holzenthal, it was an opportunity to impress on his entomology students the importance of accuracy in scientific drawings, but also for them to appreciate the skill of these pioneering entomologists and the sheer beauty of their drawings.

“The quality is amazing considering what they had to work with back then,” he said, adding: “The foundation of our knowledge of insects started in those works.”

In Entomology 5051, Holzenthal teaches students how to draw insects. It’s easier today, he notes, thanks to tools like Adobe Illustrator and Adobe Photoshop. But it’s still a challenge. For one thing, artistic license, so to speak, is not allowed.

“The purpose is to be scientifically and technically accurate,” Holzenthal said. That’s because the drawings are used in research papers to illustrate how scientists are describing new species or revising and redescribing old species.

“If one little vein is out of place, it makes a dragonfly or butterfly a different genus almost,” Holzenthal said.

Drawing skill critical for future entomologists

While all of the students learn valuable skills in the class, it’s especially important for those studying to become entomologists as they will need to provide illustrations in their research papers. And most researchers can’t afford to hire out the work, Holzenthal said.

And the research they’ll be doing is important to our future, whether you are looking at it philosophically or pragmatically, Holzenthal said.

“If we understand other living things, we can appreciate them more and see our place in the world and hopefully protect it — and it helps us understand the complexity of evolution and how things evolve,” Holzenthal said, while adding that there are many practical reasons for this kind of work, too.

“My department does a lot of applied research — how to control insects that are agricultural or human pests, for example,” he said. “For that you need to understand their lifecycle, what they eat, where they are distributed, how do they grow, what stage in the lifecycle are they most vulnerable.”

Rare books represent ‘fundamental knowledge’ of insects

Then Holzenthal circled back to the importance of the rare and historical entomological books at the Natural Resources Library.

“And all of that fundamental knowledge first accumulated in these works published by these early entomologists.”

He said he expects to draw on this collection for future classes, which is welcome news for Farrell and Gmur.

“I just want people to know they exist and are available here,” Farrell said. “Because I think when people hear ‘rare books’ they think they’re available in just one library on campus.”

The centuries old entomology books included:

- “Natursystem aller bekannten in- und ausländischen insekten, als eine fortsezzung der von Büffonschen naturgeschichte” by Karl Gustav Jablonsky. Book is from 1785.

- “Beschouwing der wonderen Gods : |b in de mintsgeachte schepzelen of nederlandsche insecten … naar ‘t leven naauwkeurig getekent, in ‘t koper gebracht wn gekleurd” by Jan Christian Sepp. Book is from 1762.

- “The entomology of Australia, in a series of monographs” by George Robert Gray. Book is from 1833.