By Carissa Hansen

Project Archivist, Upper Midwest Literary Archives

In my previous article, I explored Minnesota poet Bill Holm’s use of boxelder bugs and pigs in his writing. Now, I turn my attention to two other elements that are key to understanding Holm’s work — Walt Whitman and the concept of “failure.”

Holm’s papers include material for several of unpublished anthologies and manuscripts, including early compilations of work that would later become some of his most well-known collections of poetry such as The Dead Get By With Everything (1990) and Playing the Black Piano (2004). One such unpublished work is titled Night, Sleep, Death and the Stars and contains 60 short poems by Walt Whitman selected by Holm circa 2003. In the introduction to the anthology, Holm writes about his first experience reading Whitman’s poetry at age 11 (circa 1954) while on a trip with his mother to a department store:

“I was good for the rest of the trip, sitting in a corner of the better dress department, fingering leaves of this Bible-sized book signed not by God, but by Walt, not Walter, a banker’s name, but Walt – a farmer’s handle. I imagined a comparable book in 50 years – Sheaves of Wheat, Stalks of Corn or some similar title signed on the cover by Bill (not William) Holm.”

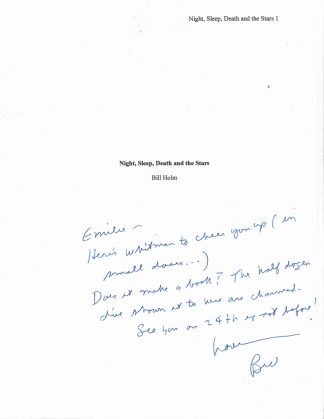

Title page of Bill Holm’s manuscript for his anthology of Walt Whitman poems titled Night, Sleep, Death, and the Stars. The page includes a note to Milkweed Editions Editor Emilie Buchwald. Holm asks her, “Does it make a book?

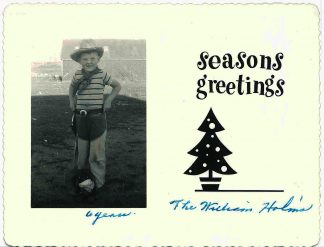

Photograph of Bill Holm, age 6, presumably outside his family’s farm near Minneota, MN.

Holm and Whitman were kindred spirits of sorts. Both rejected formality in poetic expression, Whitman in his use of free verse and Holm in his subject matter, full of gritty depictions of small-town life. Having grown up on a farm in Minneota, Minnesota, far removed from the literary hub of the East Coast, Holm appreciated the informality of Whitman’s writing and persona. Whitman gave him permission to be Bill, not William, the poet.

Whitman’s poetry continued to shape Holm’s writing for the rest of his career, including Holm’s writing about failure. In Holm’s book The Heart Can Be Filled Anywhere on Earth (1996), he references Whitman’s work while examining the connection between place and failure. In a section titled “Another idea from Walt Whitman that no one wants to hear,” Holm writes:

“At fifteen, I could define failure fast: to die in Minneota, Minnesota. Substitute any small town in Pennsylvania, or Nebraska, or Bulgaria, and the definition held. To be an American meant to move, rise out of a mean life, make yourself new.”

Holm then goes on to quote Whitman: “Vivas to those who have fail’d!” Both poets sought to subvert commonplace definitions failure. For Holm, this meant pushing against the notion that small-town life and success are incompatible.

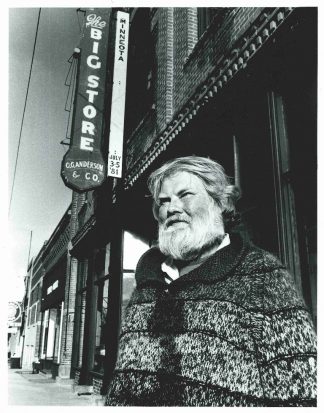

Photograph of Bill Holm in Minneota, MN in the 1990s.

In The Heart Can Be Filled, Holm alludes to feeling like a failure as he entered his 40s. By the late 1970s, he hadn’t yet published a major book of prose or poetry, and he had returned to home to Minnesota after teaching in Virginia for several years. In a piece titled “Icelanders, box elders, soybeans and poets” published in Minnesota Monthly in August 1977, Holm writes:

“I do not mean here to write my own autobiography, but rather to use myself as an example, duplicated many times in southwestern Minnesota, of the attempted escape from these bleak prairies, and of the discovery, usually after a passage of years, that you love a place, and belong there, and grow out of its black ground like a cornstalk.”

This sentence could be considered a central thesis of Holm’s writing, as so much of his work offers autobiographical and observational contemplations of place. He wanted readers to not only accept life on the prairie, but embrace it, and to accomplish that, he had to write about his own life.

Thanks for following along as I’ve explored boxelder bugs, pigs, Walt Whitman, and the concept of “failure” in Bill Holm’s manuscripts and writing! These are just a sampling of the symbols and concepts in Holm’s work, but they encapsulate the struggles and beauty of being a writer of the prairie. In processing Holm’s papers, I’m not only documenting the life and work of an important literary figure, but also a segment of life in rural Minnesota. I think often about how this “documenting” didn’t start with work in the archives, but instead, it started with Holm’s writing and the lenses through which he helps us view small-town life – such as boxelder bugs, pigs, and Whitman.

—

Funding for Prairie Poets and Press

Prairie Poets and Press has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. The Minnesota Historical and Cultural Grants Program has been made possible by the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the vote of Minnesotans on November 4, 2008. The Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund raises millions of dollars each year to support the artists and cultural heritage institutions (such as historical societies, libraries, and museums) that keep our state great, our citizens thoughtful, and our community thriving.

– Carissa Hansen is a project archivist for the Upper Midwest Literary Archives. To learn more about the Upper Midwest Literary Archives, please visit www.lib.umn.edu/mss.

The materials featured in this article are from the Bill Holm papers in the Upper Midwest Literary Archives at the University of Minnesota.