By Emily Beck, Associate Curator of the Wangensteen Historical Library, and Karen Marsalek, Professor of English, St Olaf College

It’s almost Halloween, our favorite holiday in the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine (WHL), so we’re busy thinking about all the spooky things in our collections. Since much of our material focuses on the histories of pharmacy (making medicines) and nutrition (making food), many of these books are full of recipes. The WHL’s recipe books, dating from the 1430s-to the 1900s, contain both mundane and creepy recipes for cures and comestibles.

Shakespeare’s Macbeth, originally written around 1606, features a particularly spooky recipe wherein three witches fill their cauldron with bits of real and mythical animals, plants, and even people. We’ve wondered which books in the WHL might shed some light on what these witches were up to…

FIRST WITCH

Round about the cauldron go,

In the poisoned entrails throw.

Toad that under cold stone

Days and nights has thirty-one

Sweltered venom sleeping got,

Boil thou first i’th’ charm’d pot.

ALL WITCHES

Double, double, toil and trouble,

Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

SECOND WITCH

Fillet of a fenny snake

In the cauldron boil and bake,

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork and blind-worm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg and owlet’s wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth, boil and bubble.

ALL WITCHES

Double, double, toil and trouble,

Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

THIRD WITCH

Scale of dragon, tooth of wolf,

Witch’s mummy, maw and gulf

Of the ravined salt-sea shark,

Root of hemlock digged i’th’ dark…

ALL WITCH

Double, double, toil and trouble

Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

(Macbeth, Act 4, Scene 1, Lines 12-25, 35-36)

Many books in the WHL and other rare book collections confirm that early modern women and men used similar ingredients to make medicines, and even cast spells.

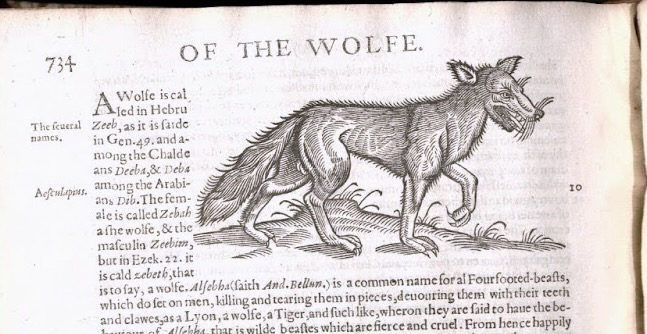

For example, the witches’ “tooth of wolf” and “eye of newt” would be familiar to readers of English books about animals. In his book, The history of four-footed beasts (1607) Edward Topsell noted that the eye of a lizard was part of a remedy for fever, and the teeth of a wolf, “being rubbed vpon the gums of young infants, doth open them, whereby the teeth may the easier come forth.” (Topsell, 1607, p. 752) Topsell also said that “The (Magi) or wisemen say, that the right eie of a greene liuing Lizard, being taken out and his hedforthwith strok off and put in a goats skin is of a great force against quartan Agues.” (Topsell, 1607, p. 251)

Woodcut illustration of a wolf. Topsell, E., Gessner, C., Moffett, T., & Rowland, J. (1658). The history of four-footed beasts and serpents (The whole revised, corrected, and inlarged with the addition of two useful physical tables / by J. R.). Printed by E. Cotes, for G. Sawbridge. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. Folio 590 T629hi 1658

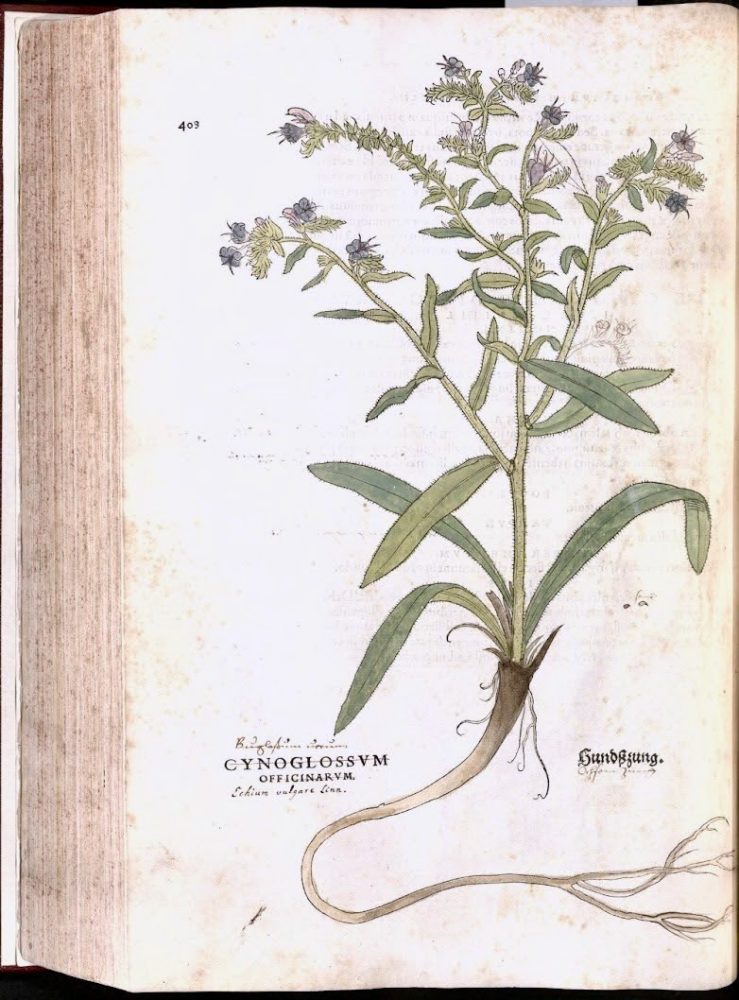

On the other hand, some of the witches’ ingredients might also refer to plants. For example, the herbalist John Gerard recommended the plant hound’s tongue for various ailments, including hair loss, saying that “the leaves stamped with old swines grease, are good against the falling away of the hair of the head”! (Gerard, 660)

Hand painted woodcut illustration of the plant houndstooth. Fuchs, L. (1542). De historia stirpium commentarii insignes : maximis impensis et vigiliis elaborati, adiectis earundem vivis plusquam quingentis imaginibus. In officina Isingriniana. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN Folio 580.01 F95.

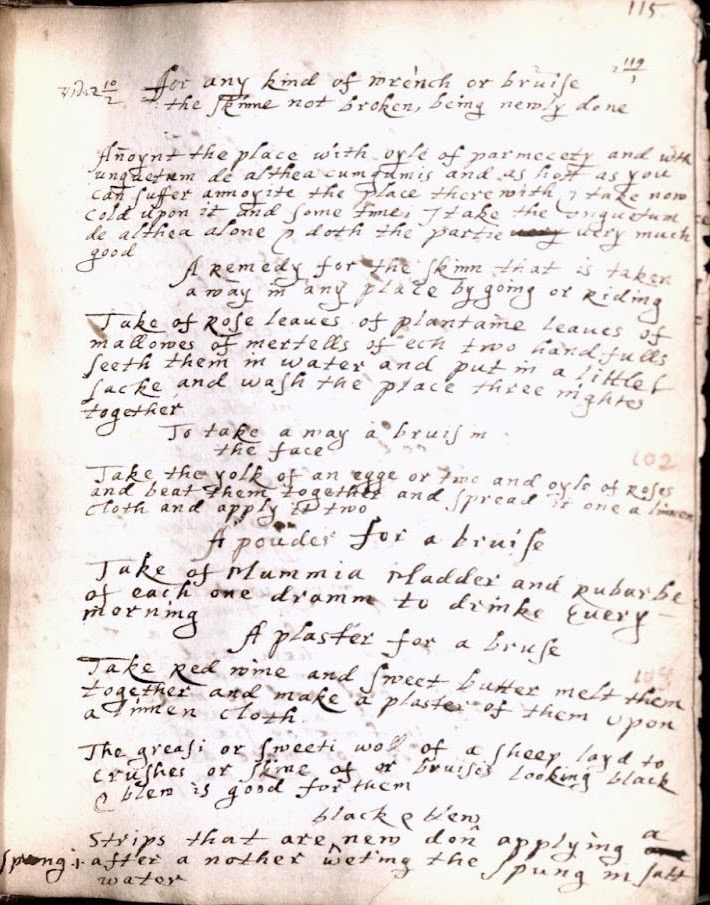

Even the more mythical-sounding ingredients, like the witches’ mummy and dragons appear in early remedies. Both are recorded in seventeenth-century recipe collections. One of the WHL’s handwritten (manuscript) recipe books, written by a woman named Mary Pewe in England in the 1600s, includes a recipe to treat bruises that includes mummy, or “mummia.” This ingredient was a resinous fluid derived from real mummies, and it was sold by English apothecaries. Instead of the local drugstore filling your prescription, the apothecary could sell you mummy for you to make your own medicines.

The recipe titled “A pouder for a bruise” toward the middle of this page includes mummia among its ingredients. Mary Pewe & Rawdon, M. (1637). Medical receipts, circa 1637-circa 1661: manuscript. 15v. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. WZ250 M489 1637

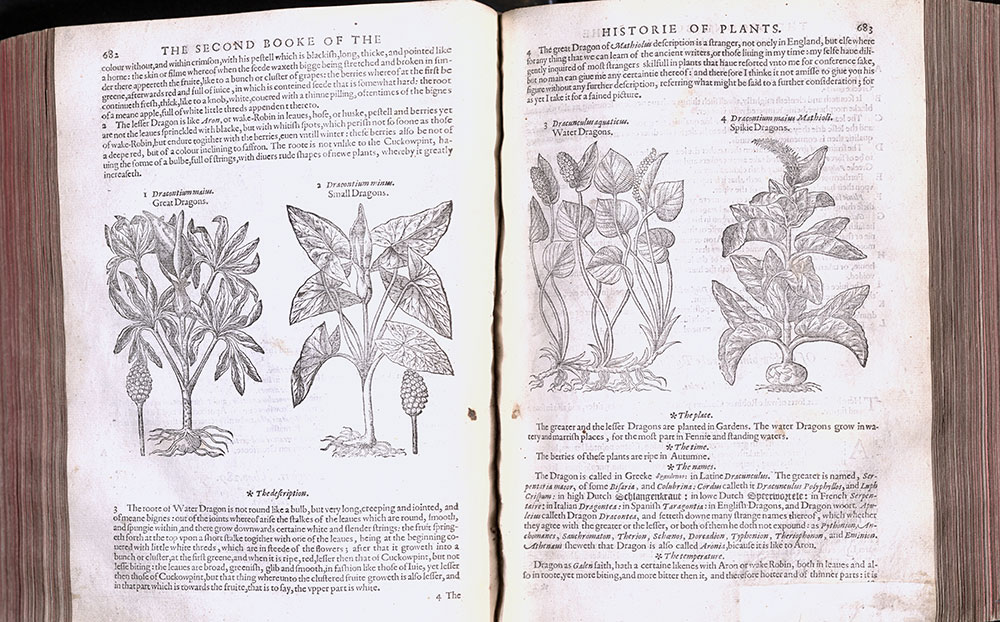

When these recipes require “dragon” they probably refer to a plant that we now call dragon lily or voodoo lily. In the seventeenth century it was used in treatments for ulcers, growths, and phlegm in the lungs. (Gerard, 684)

These pages from John Gerard’s 1607 herbal show four different kinds of plants called “dragon”: Great Dragons, Small Dragons, Water Dragons, and Spikie Dragons.” John Gerard. (1597). The Herball : Or Generall Historie of Plantes. 682-683. By John Norton. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. Folio 580.01 G31

Though early modern men and women did use “unusual” ingredients in their homemade medicines, they also followed recipes that were more sinister and supernatural, just like Macbeth’s witches. A genre known as “Books of Secrets” featured alchemical and mystical directions like those in the play. For example, the “secrets” of the medieval saint Albertus Magnus, published in the sixteenth century, describe the magical benefits of various ingredients. While herbalists recommended it as a cure for dog bites, Magnus gives a more magical application. He advises putting this plant under your toe in order to prevent dogs from barking. (Magnus, 5v.) The witches use an owlet’s wing, and Magnus said that putting the heart and right foot of a screech owl on a sleeping man will make him agree to do whatever you ask of him. (Magnus 33v)

Later in the scene, one of the witches also adds “gall of goat” to their brew. Albertus Magnus makes a potion with goat’s blood, fennel juice, and vinegar. If you annointed a man’s face with it, he would see “mervailous and horrible thinges…, and it shall seme to ym that he must dye.” (Magnus 34r-v) Similarly, when Macbeth meets the witches around their cauldron he sees horrible visions, including prophesies of his death.

The Wangensteen Historical Library is open to the public and is ready to help you with all of your historical recipes research, whether or not it’s spooky! Visit us online to learn more about the collection at z.umn.edu/whl.

For further reading

Leonhart Fuchs. De historia stirpium commentarii insignes : maximis impensis et vigiliis elaborati, adiectis earundem vivis plusquam quingentis imaginibus. 1542. In officina Isingriniana. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN Folio 580.01 F95.

Edward Topsell, & Gessner, C. The historie of foure-footed beastes ; describing the true and lively figure of every beast, with a discourse of their severall names, conditions, kindes, vertues (both naturall and medicinall). Countries of their breed, their love and hate to mankinde, and the wonderfull worke of God in their creation, preservation, and destruction. Necessary and profitable to all sortes of men, collected out of divine scriptures, fathers, phylosophers, physitians, and poets, amplified with sundry accidentall histories, hierogliphicks, epigrams, emblems and epigrams and other good histories, collected out of all the volumes of Conradus Gesner, and all other writers to this present day. Printed by William Iaggard. 1607. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. Folio 590 T629.

Gerard, J. (1597). The Herball : Or Generall Historie of Plantes. By Iohn Norton. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. Folio 580.01 G31.

Mary Pewe & Rawdon, M. Medical receipts, circa 1637-circa 1661: manuscript. 1637. Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. WZ250 M489 1637.

Albertus Magnus. The Booke of Secretes of Albertus Magnus of the Vertues of Herbes, Stones and Certayne Beastes. also a Booke of the Same Author of the Maruaylous Thinges of the World, and of Certayn Effectes Caused of Certayne Beastes. 1565.

Geraldo De Sousa, “Cookery and Witchcraft in Macbeth,” Macbeth: The State of Play, edited by Ann Thompson, Bloomsbury 2014, 161-182.

Wendy Wall, Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern Kitchen, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Can I please ask for some clarification on this? There appear to be no sources that provide ‘eye of newt’ as an alternative name for ‘mustard seed’ prior to the 21st Century. Indeed, the whole idea that the ingredients of the witches’ cauldron are merely herbs and plants (rather than the gruesome items they appear to be) originates with Wiccan author Scott Cunningham writing in 1985. At the time, many modern pagans were concerned to reinvent the negative images of witches found in folklore, and claiming ‘eye of newt’ was a harmless herb was part of that.

The proposal that Shakespeare’s witches were really only using herbs doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. While it might be possible to argue that, for example, ‘tongue of dog’ was really the herb houndstongue, there is no way that ‘finger of birth-strangled babe / ditch-deliver’d by a drab’ refers to anything but what it says; and the less said about the human liver, the better. Shakespeare was writing to please James I, who was afraid of witches. His weird sisters were meant to be evil, ghoulishly and exaggeratedly so.

Moreover, the use of animal parts in historical magic is, as I’m sure you’re already aware, well documented. Agrippa provides plenty of examples. The motivation behind trying to reinterpret Shakespeare’s malefic witches as harmless herbalists was part of the movement in the 1980s and 90s to reclaim witches in general for benevolent Wiccan purposes.

Contrarily, Shakespeare’s works are known to be playful and full of double entendre. It’s notable that the “”liver of blaspheming Jew,” is exactly what one would call liver which has been prepared to be eaten… by a jewish butcher, who were the common folk who ate them (as they were seen, culturally, as tasty, while others were weirded out by them; many people despise liver and onions today who didn’t grow up with it). So even in that there are parallels. (All jews are blasphemers, as they don’t believe in the catholic church, under the commons of the story).

Given further the context of the ambiguous things the witches give after this scene, if many of these things *were* given to be ambiguous themselves, that would certainly fit in with these themes, aye?

I’d love to know your source that Scott Cunningham made it up? Or that is originates with Cunningham at all. I own Cunningham’s Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs. There is no mention of Eye of Newt in it that I have seen. Adder’s Mouth and Tongue of Dog are mentioned but not Wool of Bat, Eye of Newt or Toe of Frog. I think it is fair to ask which book apparently has this as you are accusing a man of having lack of integrity and making things up.

Cunningham in his books generally include information on source material and did his research. So if you have a source that Cunningham is the origin of Eye of Newt = Black Mustard Seed then I’d love to know. I would also point out that 1985 is the 20th century and prior to the 21st century. I realize that isn’t want you mean. You mean before 1950. Under Mustard there is no Mention of Eye of Newt nor is their any listing for it as an alternative name for Mustard seed.

Are you referring to the Roman Agrippa or Heinrich Agrippa? Either way, both of them were biased, in somewhat opposite directions, and we should be skeptical of their reports. While I have no doubt that animal parts were used in occult practices and folk medicine, many plants and their parts were referred to using names easy to memorize. “Heart” referred to the seed, “toe” to the leaf, “guts” to the roots, etc. Here are two citations that might be helpful: Andrew Yang in his work ‘Plant Names in Old and Middle English: Problems and Trends in Taxonomy’ and, more specifically, Oswald Cockayne’s ‘Leechdoms, Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England: The History of Science Before the Norman Conquest.’

Additionally, anyone who knows anything about plant based medicine and poison would rather eat a baby’s toe or a bat wing than boiled yew and wormwood. It’s a good way to join the dead, not raise them. A lot of the herbs mentioned in the verse refer to those that cause hallucinatory experiences, but can also be deadly. In my opinion, the modern “Wicca” movement has destroyed and convoluted much of occult history, as so much of their practices seem arbitrary. Frankly, the stereotypical “witch” didn’t exist outside of religious dogma until Wicca. It was a way for the aristocrats and the churches to wrestle the last bit of control of medical treatment from the peasantry. The innocent people painted as evil “witches” deserve to be stripped of the negative, ridiculous stereotype. They were primarily local “granny women” and midwives with any outcast or rebellious thinker thrown in for good measure. So if they tried to make witches seem harmless, I’m glad. Because they were. It was a genocide in some parts of Europe, and we should remember it as such.