By Emily Beck

It turns out that a potluck is a perfect way for ending a semester of discussion on the history of premodern food.

The Premodern Food Laboratory — a part of the Consortium for the Study of the Premodern World — visited the Wangensteen Historical Library to examine handwritten recipe books and share homemade historical recipes.

The participants spent the semester discussing everything from Anglo Saxon dairy practices to ancient manioc farming in El Salvador. They then celebrated by sharing dishes like butter salted with seaweed flakes from a medieval Irish recipe and vegetarian soup from a mid-19th century German American recipe.

The Libraries are a home for food historians

The University Libraries is an ideal home for this kind of cross-disciplinary, interactive research.

The resources about food and cooking at the James Ford Bell Library, the Kirschner Collection, and the Wangensteen Historical Library — among others — form a large collection of material about food waiting to be uncovered.

Enjoy our photo diary showcasing the treats cooked up by the Premodern Food Lab this December!

Potluck photo diary

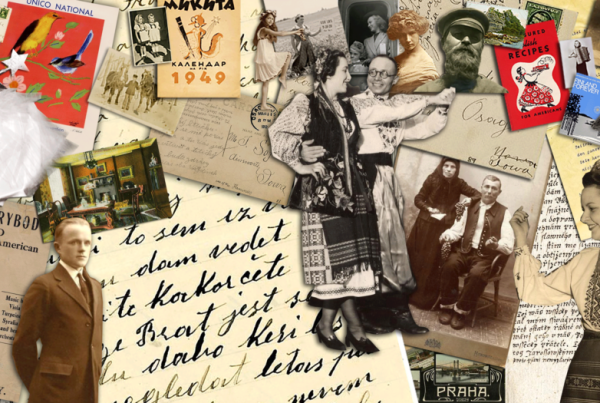

Participants examine handwritten recipes in the Wangensteen Historical Library collection, which holds over thirty handwritten recipe books that cover topics such as food, medicine, animal care, and the production of household goods like ink and soap.

This fresh cheese was made from an early mediterranean recipe. The original instructions called for the milk to be stirred with a fig branch, which would have caused the heated milk to separate into curds and whey. Author and University of Minnesota staff member Gayla Marty rolled the formed cheese in dried hyssop.

This bread was made from a recipe that archaeologists wrote after reverse engineering a loaf of carbonized bread found in Herculaneum, a city near Pompeii that was also destroyed when Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD. Like modern sourdough, this bread began with a soured starter, or biga acida.

This platter includes two different kinds of fresh butter made from a Medieval Irish recipe, and cheese straws, made from a mid-19th century recipe. The yellow butter was made with extra salt since the Irish tended to use lots of salt in their cooking. The paler, spotted butter was salted with seaweed flakes. In years when there was not much or any salt being imported to Ireland, dried seaweed could be used to salt – and thereby improving the flavor and preserving the butter. Erin Crowley, graduate student in the Anthropology Department, made the butter and reported to the group that there are other medieval Irish recipes that include seaweeds – such as a dessert of boiled milk, seaweed, and honey.

James Ford Bell Library Curator Marguerite Ragnow made this medieval English onion and cheese pie. Since the recipe called for “green” (or, young) cheese, Marguerite used ricotta to make this savory pie. The recipe comes from a medieval manuscript that was printed and published in England much later. The University Libraries has a copy of the volume that was printed in 1780!

Archaeologist Lydia Garver made this mid-19th century German-American soup from a manuscript recipe book. She determined that this plain but filling soup made that was made with homemade noodles and potatoes was probably meant to be served to people recovering from illness. If you want to learn more about German-American cooking in the 19th century, check out season 8, episode 3 of A Taste of History, featuring Lydia.

This delicious spread was made from a Babylonian recipe for the Jewish Passover food haroset. Made from dates, tahini (sesame paste), and balsamic vinegar, this haroset recipe is still eaten today. History department graduate student Noam Sienna wrote about the history of haroset and this specific recipe in this article in Forward.

Researchers contemplating some of the challenges of cooking accurately from historical recipes: how have ingredients changed over time? What do you do with a recipe when it doesn’t tell you ingredient amounts, or the length of time it takes to cook the food? How do you adjust an historical bread recipe for a modern oven when people in the past used brick ovens?