By Annie Hoffman

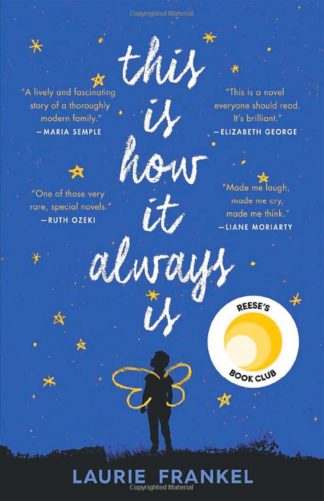

Laurie Frankel’s third novel, This Is How It Always Is, tackles the sprawling quotidian reality of an upper middle class family of seven. Parents Rosie and Penn are an ER doctor and a writer, respectively.

Laurie Frankel’s third novel, This Is How It Always Is, tackles the sprawling quotidian reality of an upper middle class family of seven. Parents Rosie and Penn are an ER doctor and a writer, respectively.

The book’s third-person limited narration offers both parents’ thoughts, positioning the two collectively as the protagonist. Together they take on Halloween costumes and shifts in the ER and a never-ending bedtime story.

The novel’s focus, however, settles upon the couple’s youngest child. This child starts out named Claude and goes on to be named Poppy, which sends Rosie and Penn Walsh-Adams on a desperate search for the best way to raise their gender nonconforming child.

The plot

The novel begins at Claude’s conception. The couple already has four boys. Rosie isn’t superstitious, but she still follows a German folkloric suggestion to conceive a girl by sticking a wooden spoon under the bed before sex. Still and all, she gets Claude. This fourth son is only three when he begins saying that he wants to be a girl when he grows up.

Rosie and Penn read books, consult a “multi-degreed social-working therapist-magician,” and talk to Claude’s teachers. They are eager to support their child but unsure how best to do so.

Claude becomes Poppy, and it’s wonderful but not always easy. As Poppy starts drawing herself smaller and smaller in the family portraits she makes, her parents worry that a cruel world will make their child disappear entirely. Treating a trans ER patient who was brutally beaten when her transness was discovered crystalizes Rosie’s fears. She moves her family from Madison, Wisconsin, to Seattle, Washington. Things are “gayer” there, and she believes her child can be safe.

Not a ‘woe is me’ story

This book could quite easily become a “woe is me” story, situating Poppy’s parents as victims of difficult circumstances and thus perpetuating notions of transness as deviant or inconvenient. But Frankel sidesteps this pitfall.

For Rosie and Penn, standing by their child is not a burden but merely a parental responsibility. The problem is not their child — it’s the world.

The book’s title is drawn from a conversation in which the parents acknowledge to one another that parenting any child is impossible and necessary. It is never easy. This is how it always is, they say to each other, and then they move across the country.

On to Seattle

In Seattle, the fact that Poppy was born Claude sort-of accidentally becomes a secret. But the secret grows heavier, and eventually sneaks out. This sends Poppy into her room to shave her head and put on her baggiest sweatpants and come out insisting miserably that she has to be Claude again.

Here, the story engages unflinchingly with the toxic and bewildering ways that gender norms and transphobia operate in our society. Rosie and Penn talk in circles about what constitutes a boy or a girl. They wonder how and when to offer puberty blockers or surgeries.

As they struggle to help their suffering child, we wonder how Claude/Poppy will make space for themselves in the hostile world. In due course Frankel offers us her answer, but I won’t spoil that discovery.

An alternative construction of gender and transness

In the final section of the book, Rosie and Claude/Poppy embark on a journey, encountering people who offer an alternative construction of gender and transness. This section is also characterized by a structural shift: The narration broadens to allow us to see things directly from Claude/Poppy’s perspective. While this loss of specificity distracts from the narrative intensity at the climax, Frankel’s facility in shifting seamlessly between perspectives carries us through.

This Is How It Always Is tells a lot of story using a lot of words, rewarding a reader’s commitment by delivering hilarious dialogue and brewing characters who get stronger over time. It demonstrates that caring so much that it hurts will always be enough, even when it isn’t. It is a portrait of familial love in a world that isn’t changing fast enough.

This is the second in a series of reading picks by current and former UMN student employees at the University Libraries. The books are found in the Robert and Virginia McCollister Collection for Contemporary Literature at Wilson Library.

The collection provides access to many of the Libraries’ most page-turning popular books. Annie Hoffman is an undergraduate in the UMN Dance program and a student journalist with the Libraries Communications office.