Students in Dominique Tobbell’s Technology and Medicine in Modern America class had a unique opportunity to place contemporary issues in medicine and health care in their historical context.

After adopting an artifact from the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine, students dove into the research process using both present-day and primary source materials to discover how their artifact was used in the past and how it has shaped contemporary practice.

At the end of the course, students wrote a blog post about their artifact. Along the way, they developed research and communication skills while sharing historical insights in ways that are accessible and useful to the public.

This is the second in a series of three articles showcasing the work of Tobbell’s students. In this post, U of M College of Biological Sciences student Sarah Copeland explores the history of artificial eyes.

Artificial eyes: Porcelain past, programmable future

By Sarah Copeland

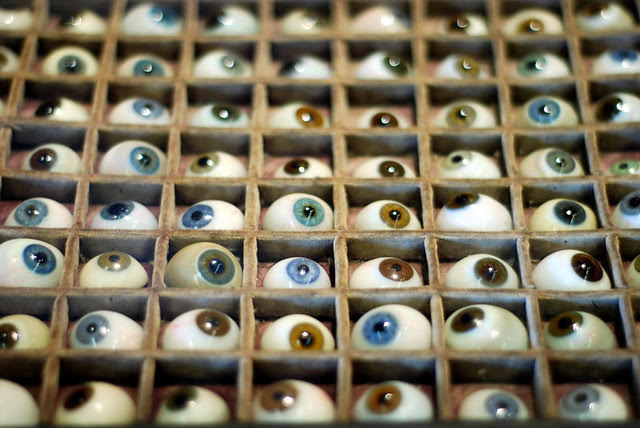

It’s a scene straight out of a Halloween movie. Rows upon rows of glass eyes, staring out at the world with an eerie vacancy that’s usually reserved for porcelain dolls. Their irises are hand-painted with exceeding care, marbled with various shades of blue and brown. The lacquer covering them makes them feel almost alive. But this case of eyes represents over a century of innovation in the field of ocular implants and prosthetics. From gold balls to bionic implants, eye implants and prosthetics have progressed rapidly in the past century and a half.

A case full of glass artificial eyes of various colors from the Wangensteen Historical Library (1).

Methods and materials

Artificial eyes began to see widespread use after the end of the Civil War. Many soldiers returned home with wounds to their face and limbs, prompting the development of the prosthetic field. Prosthetics saw a boom of usage during the Reconstruction era, and this expanded use saw the process of fitting and using an artificial eye become much more streamlined than it was in the past (2).

After the damaged eye was surgically removed, a gold ball would be inserted into the empty socket and attached to a stump of remaining tissue. This ball serves as a point of attachment for the artificial eye. The eye would then be ordered from a medical supply company, where color and size could be specified. Once the artificial eye arrived, it was ground down with a grindstone to fit comfortably into the socket (3).

These eyes were historically made of glass and porcelain, but with the advent of plastic, most eyes were made with plastic. The plastic was painted to mimic a sclera and iris, and the plastic shell was coated with an acrylic lacquer to make it seem more life-like. Due to this hand painting process, the eyes could be customized to match the patient’s remaining eye. Plastic is more lightweight than traditional glass and is less irritating to a patient’s tissue, making it a more suitable substance for artificial eyes (3).

Pioneering surgery

Traditionally, these artificial eyes were immobile, remaining stationary in a patient’s socket. But in the 1940s, a new technique was pioneered that allowed an artificial eye to move in its socket. The eye was attached to the remaining muscle in the eye socket and stitched into place, allowing for the patient to move the fake eye along with the remaining real one. While purely cosmetic, this technique shows the advancements that were being made in ophthalmic surgery regarding eye implants (4).

Another breakthrough in surgery regarding ocular implants involves the eye socket itself. Rarely, genetic disorders may cause someone to be born without an eye socket. New techniques regarding reconstructive surgery in the 1930s allowed surgeons to construct an eye socket out of tissue from other parts of the body. While the function of sight was not gained through this surgery, this new technique was pioneering in the field of reconstructive surgery, as well as therapeutic for the patient (5).

Fitting in

Most of the devices and surgeries described above provided no clear-cut medical benefit to the patient. Indeed, it may have been easier and cheaper in most cases to let the wound heal and wear some sort of covering over the socket, like an eyepatch. But while there was no primary physical benefit to these procedures, the psychological benefit for the patient was well worth the ordeal.

Losing an eye is a very traumatic thing. Going from binocular to monocular vision takes a lot of adjustment, and the disfigurement can cause psychological trauma for the patient. Having a glass eye provides some sense of familiarity to the patient and allows them to not feel as much like they’ve permanently lost a part of themselves. The eye can also help prevent ridicule from peers by helping the patient blend back into normal society.

The future

While artificial eyes are still relatively common in the world of ocular implants, new advancements in computers have led to advancements in ocular surgery. New bionic implants rewire the nerves in the eye, circumventing damaged parts of the eye and sending signals straight to the brain. This advancement, with further work, could eventually lead to a new and better treatment for blindness (6).

The future of artificial eyes and ocular implants seems more and more rooted in the fields of robotics and computers, but it is still important to learn where these advancements originally started. From porcelain to nano-wiring, ocular devices have come quite a long way.

About the author

About the author

My name is Sarah Copeland. I am a sophomore in the U of M College of Biological Sciences studying Biochemistry and hoping to go to veterinary school. I took this course because I was very interested in studying how medicine has changed throughout America’s history.

Works cited

- Gwendolyn True, Monsieur Faurie’s glass eye collection. Source: Gwendolyn True, New Mexico-Taos. 2007, Digital Image. Available from: Flickr, https://www.flickr.com/photos/25748965@N00/2138683334/in/photostream/ (accessed December 09, 2019).

- Mills, L. “Ocular Prosthesis.” Archives of Ophthalmology 37, no. 5 (January 1947): 700–700. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1947.00890220717019.

- Gougelmann, Pierre. “The Fitting Of Artificial Eyes.” Archives of Ophthalmology 2, no. 1 (January 1929): 76. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1929.00810020081008.

- “ NEW ARTIFICIAL EYE STITCHED IN PLACE AND MOVES.” Los Angeles Times, September 17, 1946.

- “Eye socket is made where none existed: Surgeon soon to operate to install an artificial eye for 3-year-old girl.” New York Times, July 10, 1937.

- Servick, Kelly, Jeffrey Mervis, David Malakoff, Richard Stone, and Eva Frederick. “New Technologies Promise Sharper Artificial Vision for Blind People.” Science, October 31, 2019. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/10/new-technologies-promise-sharper-artificial-vision-blind-people.