By Allison Campbell-Jensen

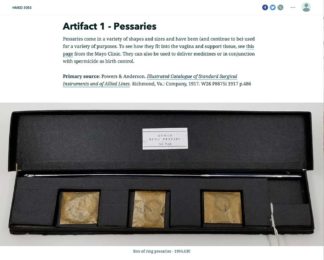

Forceps? “These are so big, so heavy.” A sanitary sponge, used historically for female-controlled contraception: “How is that sanitary?” Pessaries and other health-related tools for women: “Wow, this was inside someone, and I’m touching it!”

Forceps? “These are so big, so heavy.” A sanitary sponge, used historically for female-controlled contraception: “How is that sanitary?” Pessaries and other health-related tools for women: “Wow, this was inside someone, and I’m touching it!”

The artifacts from the Wangensteen Historical Library elicit immediate, visceral reactions among the students in Dominique Tobbell’s Women, Health, and History course.

Well, they typically have in the past decade, when students have had the opportunity to handle these artifacts. Not this spring! The team of Tobbell and teaching collaborators Emily Beck and Lois Hendrickson of the Wangensteen Historical Library had to take a different approach, as HMED 3055, like all the instruction at the U of M, moved online to help stem the threat of COVID-19 infection. Fortunately, experience in teaching sections of the course and a good dose of planning eased the transition.

Experience behind a quick turnaround

With just a couple of days warning prior to the shutdown of library buildings, Beck created a History of Contraceptives story map for the 44 students enrolled in the course. She outlined the story map’s concept and there were still a couple of students around to help with the materials. Then a friend of the Wangensteen Library came in to videotape Beck.

“The story map was such a great activity,” Tobbell says. “The students seemed to respond really well to it. And it came as close as possible to replicating the in-person hands-on experience the students usually get with their time with artifacts from the Wangensteen.”

Gender and equity issues arise

Dismay and shock that women used borax, Lysol, and other chemicals for spermicides, she adds, helps the students better empathize how it was to be a woman attempting to control conception in an earlier era. Tobbell says late 19th-century manuscripts also reveal that physicians “actually thought if women didn’t marry, that would cause pathology. As treatment, they recommended marriage, having children, and avoiding strenuous intellectual and physical activities such as education and paid work.”

So these primary source materials from the Wangensteen reinforce the learning goals, which include issues of gender and equity, Tobbell says, while creating new avenues for thinking. Many are eye-opening ideas for the students, most of whom are young and haven’t previously encountered such concepts.

To facilitate student discussion, Beck built interactions into the story map. Creating a story map, says Hendrickson, requires creativity to develop the arc of the story. The choice of items to highlight was helped, she says, because “in the past we’ve done really good assessments of students’ use of this material.” In addition to the artifacts, students were asked to contextualize them using digitized selections from historical rare books from the Wangensteen collection. “What makes this a unique active learning situation,” Hendrickson says, “is the combination of objects and rare books.”

Enrichment from primary sources

Over the 10 years or so that Beck and Hendrickson have worked with Tobbell, they have responded to her regular updating of the course. Tobbell is, for example, moving away from narratives focused on the history of white women. “I was talking about nurses and centered on black nurses,” she says, “and Emily and Lois found new materials from and about black nurses in the Wangensteen collection.”

Along with Tobbell, who is Director of the History of Medicine department, Beck and Hendrickson also collaborate with faculty who teach such subjects as French, rhetoric, design, and art history.

“I feel like we are really innovative in what we doing,” Hendrickson says, in primary source teaching. And both appreciate Tobbell for investing time and effort in their teaching partnership.

The feeling is mutual. Talking about the story map, Tobbell says: “I’m so grateful to Emily for creating such an opportunity for the students!”

View the Story Map resource