By Allison Campbell-Jensen

Skeptical that Christopher Columbus had discovered a route to India, Amerigo Vespucci consulted the journals of Marco Polo, says Gregory Hedberg, donor of a portrait of the explorer to the James Ford Bell Library. The costumes described by Polo and Columbus didn’t match up, so Vespucci sailed from Europe to learn more.

It was he, Hedberg says, who determined that the land now known as South America was new to Europeans.

Vespucci’s connection to the Bell’s Waldseemüller map

Letters purportedly written by Vespucci of his exploration of the coast of what is now Brazil to the South Atlantic inspired German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller and a scholar working with him, Martin Ringmann, to give America its name, according to Marguerite Ragnow, curator of the James Ford Bell Library. The name is on “one of the most important documents in the Bell Library collection,” she says. It is a globe gores — the printed map that gets cut out and pasted on a ball to form a globe — created in 1507 by Waldseemüller.

In addition, Ragnow says, Waldseemüller created a large 12-panel planisphere (a flat table or wall map) to accompany the globe gores, which also used the name America. He and Ringmann published a little book to go with them, ”Cosmographia introductio” (Introduction to Cosmography), to explain their importance and why they attributed the discovery of a new continent to Vespucci — and named it America.

“The Waldseemüller map, the many editions of both the Waldseemüller/Ringman publication and Vespucci letters, and the many publications not only derived from them, but which were based on voyages inspired by them, lie at the heart of the Bell Library’s Americana collection,” Ragnow says. “The discovery of America, for good or ill, changed the world,” she says, and both Vespucci and Waldseemüller played significant roles. She notes: “Adding a close to contemporary portrait of Vespucci to the collection is very fitting and helps us round out the story of the naming of America in a unique way.”

A donor’s story and the Leonardo connection

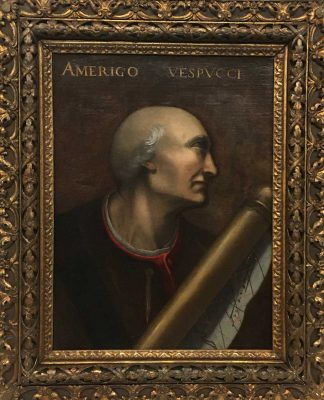

“If you [the U of M Libraries] didn’t have the map, it wouldn’t make much sense” to give the painting, says Hedberg. A native of St. Louis Park who has long lived in New York City, he is a portrait collector who has owned the painting for about 25 years. The 16th-century portrait is attributed to Cristofano di Papi, as is a similar one in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

As described in Hedberg’s documentation of the piece, this portrait is believed to be derived from a charcoal drawing that Leonardo da Vinci made of Amerigo Vespucci, which was described in Giorgio Vasari’s “Lives of the Painters.”

In 1960, the art historian C. Ernest Cooke examined the painting and concluded: “Very characteristic of Leonardo is the style of the present portrait. The treatment of the face and neck closely resembles that in the authentic work of Leonardo, such as the drawing of Savonarola (Albertina, Vienna) and the unfinished painting of St. Jerome (Vatican Gallery, Rome).”

Noting the portrait’s resemblance to the image of St. Jerome, Hedberg writes: “Unlike a typical Renaissance profile portrait which is quite static, Vespucci is depicted with his neck straining upwards which adds a quiet sense of arrested movement and a bit of dynamism to the painting.”

Who commissioned the portrait?

The Vespucci family became very wealthy based on the sale of Amerigo Vespucci’s letters, so they may have commissioned the portrait, writes Hedberg. Another possibility, he says, is that it was commissioned by Paolo Giovio, a historian whose collection of portraits of famous men became one of the first art museums.

There is no concrete documentation, however, that Giovio owned a portrait of Amerigo Vespucci. This painting on linen resembles a portrait on a panel in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Writes Hedberg: “Numerous other portraits of famous men in the Uffizi collection (most copied by Cristofono di Papi from paintings in the Paolo Giovio’s collection) are also the same size with similar inscriptions at the top. If a sitter was particularly famous, like Vespucci, Cristofano di Papi would often do more than one portrait.”

So perhaps that was the origin of this portrait?

The mystery remains but, for the donor, the connection is clear: The Bell Library has the map that named America that connects to this gift, a 16th-century portrait of America’s namesake, Amerigo Vespucci. Adds Hedberg: “I think James Ford Bell would have appreciated this portrait of a famous man.”