By Allison Campbell-Jensen

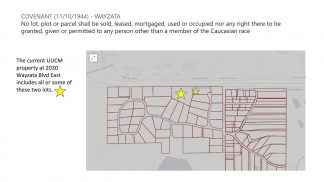

About 10 years ago, the Unitarian Universalist Church of Minnetonka decided to build a new church. The church had been founded about 50 years earlier and wanted to stay in the neighborhood. By choosing to stay close to their original site, however, the church had to purchase a property with a racial covenant on it.

Historically, racial covenants were included in deeds to bar non-whites from owning or even occupying the property.

“We realized it had a racial covenant on it and it was disturbing to us,” says church member Kate Flom, “but we didn’t know what to do about it.”

Revealing structural racism

The Mapping Prejudice Project “really brings home how responsible we all are, that we have been, for segregation in our community and the disadvantages that communities of color suffer in the present day,”

—Kate Flom

But then Flom heard about the Mapping Prejudice project, which has been training volunteers to find racial covenants in Hennepin County deeds. The data then is mapped to visualize the racial discrimination of the past which continues to have repercussions for people of color today. For example, owning a home has been a way for families to build and pass on wealth, but Black people were denied that right or shunted into certain neighborhoods.

“It’s critical to expose these discriminatory practices and help the community understand how they contributed to the structural racism we still see today in housing, education, lending, employment patterns, criminal justice, etc.,” the project team wrote in a statement.

Flom watched the 2019 documentary about the Mapping Prejudice project, “Jim Crow of the North.” She is a member of the church’s Social Justice Ministry, and after the killing of George Floyd in May 2020, the group began talking about doing something with Mapping Prejudice.

Flom watched “Jim Crow of the North” again. “Every time I watch it, I’m appalled,” she says. “And also I realize some new truth about how widespread this discrimination was and how deliberate this discrimination was.”

That the neighborhood around the church is covered with racial covenants — and their own church property has a covenant — makes this a compelling issue for Flom and, she hopes, her fellow church members. (Flom notes that she speaks only for herself, not her church.)

Supporting Mapping Prejudice

In January 2021, the Unitarian Universalist Church of Minnetonka chose Mapping Prejudice to receive their social generosity offering. They also hosted a virtual training in unearthing racial covenants, led by project member Penny Petersen, and heard a presentation from Director Kristen Delegard on Sunday, Jan. 10. The church also has applied to the Just Deeds Project for legal help removing the covenant from their deed.

The Mapping Prejudice Project “really brings home how responsible we all are, that we have been, for segregation in our community and the disadvantages that communities of color suffer in the present day,” Flom says. “I’m hopeful in understanding that long history better, we will be more willing to take action to change the way our community has been divided.”

Delegard praises the church. Even though racial covenants were all over the area, Mapping Prejudice has not been able to engage large numbers of people there in the work.

“They are the first and see the immediate connection to their congregation,” she says. “They are giving time, money, and a commitment to social change to this effort. I hope that they will be recognized as trail blazers.”

The Mapping Prejudice team has expanded the project to Ramsey County and also has federal funding to refine its techniques and digital tools to make it easier for other communities to do this work. Volunteers who reveal the racial covenants are the bedrock of this community-engaged research, which helps all recognize the legacy of racial discrimination in housing and lays the groundwork for a more equitable future.

Donate now to Mapping Prejudice Learn how you can help