By Allison Campbell-Jensen

In seeking rare materials, size matters less than the folding of a book’s pages and arrangement of leaves within the book’s structure. Two scholars of the early modern period came to use our special collections at the Libraries in February 2020. They noted that it was difficult to find information about the bibliographic format of hand-press materials — and that it would be helpful for scholars to have. So, they talked with our catalogers about it, and one of them, kalan Knudson Davis, came up with a solution.

The creative act of cataloging

Knudson Davis calls cataloging a courageous act. It’s the hard, creative work of description to make items findable.

“Cataloging is an active process, it’s a collaborative process, and it’s something that happens on a massively, globally, and diverse scale, by this highly distributed network of highly trained individuals,” she says.“Cataloging is the process of creating opportunities for intellectual discovery.”

As with other skills, such as doing yoga, or playing a musical instrument, cataloging is something that a person gets better at with practice. The resulting library catalog is a living record that is constantly being maintained, updated, and added to over the course of time. These library catalog records typically contain such information as a work’s author, publisher, contributors, and subject, as well as physical description.

Rare materials cataloging must go further than this, because the materials are not simply texts but also objects or artifacts. When Knudson Davis catalogs rare materials, she also considers their provenance (who owned them), distinctive features or imperfections, and descriptions of bespoke bindings. The bibliographic format of hand-press book, typically produced from about 1500 to 1800, previously had been included in the same cataloging field as the overall physical dimensions of the work, making it difficult to pull out.

“Cataloging is the process of creating opportunities for intellectual discovery.”

—kalan Knudson Davis

To illustrate, she explains that folding the paper for printing can result in more pages, albeit at a smaller size. If one folds a piece of paper once, one has a folio; fold it twice, a quarto; fold it again, and one has an octavo-sized page. By carefully examining the watermarks and chain-lines within the hand-press pages, one can determine how the book was constructed. This is the information the scholars were seeking.

“Around the same time as we were having these conversations with these early modern scholars who were using our collections,” Knudson Davis says, “the MARC standard just so happened to develop to a point where it had a field where this information could go.”

Weaving a path from MARC 300 to MARC 340

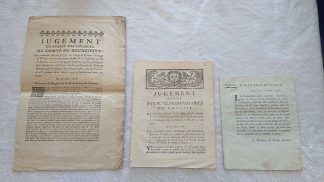

In this image, the title on the left is issued in Folio (a hand-pressed sheet folded once), but the center and right are both issued in Quarto (a hand-pressed sheet folded twice). Of the latter two, the original folded-sheets of hand-press paper were different sizes resulting in one Quarto being much smaller than the other Quarto. Nevertheless, they are both considered Quarto.

MARC (MAchine Readable Cataloging) is the language that catalogers use so that they can share information about their libraries’ holdings. With the addition of the MARC 340 subfield m, information about rare materials’ pages bibliographical format and the imposition of sheets going through the press could be moved from MARC 300 subfield c.

It was about a decade ago that Knudson Davis started preparing for moving the information when she took her first computer programming class. Initially, she felt somewhat intimidated about programming; then, with success, she felt exhilarated. She later learned that some of Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace’s first designs for the analytical machines that evolved into computers were based on the Jacquard machine used in complex weaving.

The hand weaving artistry that Knudson Davis practices (as did her grandmother before her) informs her computer programming, she says.

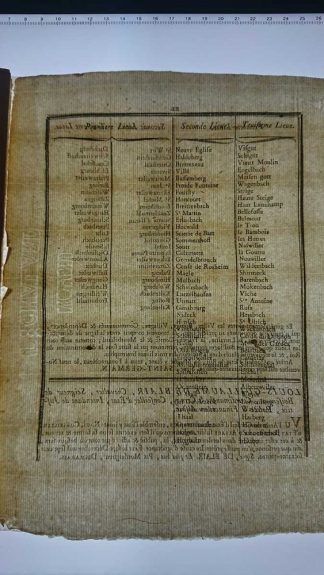

In this image, the hand-pressed paper has horizontal chain lines with a distinctively clear watermark located in the middle of the spine confirming the bibliographic format as Quarto (4to, quarto, 4°).

“Hand weaving on a loom and programming share common characteristics: Loops (blocks), syntax (drafts), and positive (weft-facing) and negative (warp-facing) binaries.”

And the Python language she uses to manipulate library metadata is even easier than weaving, she jokes, because there is an “undo” button.

In collaboration with Stephen Hearn, Metadata Strategist, and with Christine-DeZelar Tiedman, Metadata and Emerging Technologies Librarian, Knudson Davis discussed the scholars’ suggested changes, what would be needed to existing cataloging policy and what the data outputs should look like. Creating a script with Python to capture this information, Knudson Davis looped it through 118,358 records using an automated batch process. She ended up enhancing 1,891 rare materials records with bibliographic format information, “while also adding aspects to align our legacy data more closely with the library data standards of tomorrow.”

This successful pilot is the springboard for her next project: To create a platoon of rare materials catalogers who know Python and could use the script she created to get the same or similar results at their own libraries.

The more, the better, for cataloging for the future.

I am delighted that the details of page preparation and binding will be available to users of the prints and books. This is vital information. In my own work, a manuscript volume (chansonnier) whose contents seemed to be without plan or purpose found its first solid clue in the fact that its gatherings were made in groups of six leaves. That was sufficient to identify it as a product of the city of Naples, opening a view into a complex and wonderful world of ideas in that city, at the end of the fifteenth century. Now, this important signpost will guide us through the world of books.