By Allison Campbell-Jensen

The Cast from “Ain’t Misbehavin,” Penumbra Theatre, 1986-87. Creator: Maltby, Richard, Jr., 1937-; Horwitz, Murray; Penumbra Theatre Company Records, University of Minnesota Libraries, Archie Givens, Sr. Collection of African American Literature.

What began in the early part of the 20th century as a week dedicated to studying the history of Black people in America by the 1960s was expanding to a month. Starting in the mid-1970s, U.S. Presidents have annually proclaimed February to be Black History Month.

Yet people can explore Black history any month, taking online avenues through primary source materials and special collections available through the Libraries.

Umbra Search African American History

Umbra Search African American History (umbrasearch.org), a free database of hundreds of thousands of primary source materials, had its start at the U. The Libraries partnered with the St. Paul-based Penumbra Theatre, whose papers are in the Givens Collection of African American Literature, “to understand specifically how African American theaters were thinking about their archives … and thinking about legacy and memory and history,” says Cecily Marcus, Givens Collection curator.

During 2012, the partners brought together two forums of African American theaters’ founding, managing, and artistic directors from all over the United States.

“One of the things that came out of those discussions,” Marcus says, “is that none of us are born knowing history, let alone African American history. Many aspects of African American history are not taught systematically in schools, not necessarily even in universities.”

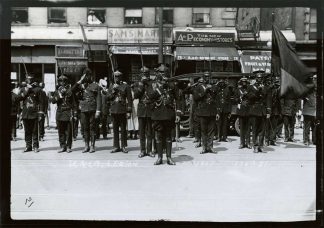

Universal Negro Improvement Association Legion, 1924, 135th St. Creator: VanDerZee, James. From the University of Minnesota Libraries, Archie Givens, Sr. Collection of African American Literature.

Without newspaper stories, photographs, and manuscripts, how could playwrights fruitfully do research? And how could they be connected to materials being digitized not only in the Givens Collection but also in collections throughout the country?

The response was to develop Umbra Search African American History, an aggregator of digitized primary source materials from the University and more than a thousand institutions around the country.

“When it’s harder to go to libraries physically, this is an incredible resource that can be accessed any time from any place,” Marcus says.

Moreover, the Libraries has gone beyond materials labeled “African American” to find other relevant items.

“If we believe, as we do, that there would be no American history without African American history, it would follow that all of our collections, not just African American collections, would speak to this history and this legacy,” Marcus says.

Thus materials from the Tretter Collection of LGBT studies, the YMCA archives, and the Social Welfare History Archive have been mined, digitized, and described with greater specificity so that they can be more easily discovered online.

The Archie Givens, Sr. Collection of African American Literature

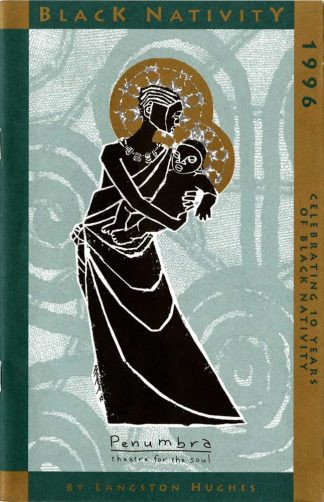

Playbill for Black Nativity, 1996, Penumbra Theatre. Creator: Hughes, Langston (Writer); Whitlock, Lewis (Director, Choreographer). From University of Minnesota Libraries, Archie Givens, Sr. Collection of African American Literature.

From the 1985 purchase of what would become the Givens Collection, it has doubled in items to more than 10,000.

“We have books, magazines, scripts, posters, a whole beautiful assortment of objects that relate to Black literature and Black history,” says Pearl McClintock, Collections Assistant for the Givens Collection and three additional collecting areas (the Performing Arts Archives, the Upper Midwest Literary Archives, and the Northwest Architectural Archives).

McClintock points out a few highlights of the collection, including a script by Eartha Kitt, and clippings about the National Negro Opera Company, which they scanned and emailed to a researcher during the pandemic. Wax Poetics magazine and the Minnesota Hip-Hop Collection are newer.

“People wouldn’t expect a hip-hop collection to be in the library,” McClintock says, “even though it is very deserving of being archived and being publicly accessible and exalted as something that is worthy of research and preservation.”

One of the most used collections in the Givens Collection is the Penumbra Theatre Company records, Marcus says, which have all been collected by the theater since its founding in 1976. It includes documentation and photographs of August Wilson plays, for instance — some of which had their premieres at Penumbra. Penumbra’s production records are digitized and online at UMedia and in Umbra Search.

The collection originated with a white playwright in New York City. Professor John Wright — now Emeritus, of the African and African American Studies and English departments — heard about the collection catalog from a student working in the Libraries.

“Dr. Wright contacted then-University President Ken Keller and Archie Givens Jr., a Twin Cities businessman and cultural leader, president of Givens Foundation of African American Literature,” Marcus says. “With the support of 10 African American families in the Twin Cities who generously supported the creation of this collection, they were able to raise money to fund the initial acquisition.” It was named in honor of Archie Givens Sr., the first Black millionaire in Minnesota, an entrepreneur, and a community leader.

Reflections on Black History Month and beyond

“This is a resource that contains important foundational history for this country that should be probed and taught and understood and interpreted every month of the year — not just Black History Month.”

—Cecily Marcus

“This is a resource that contains important foundational history for this country that should be probed and taught and understood and interpreted every month of the year — not just Black History Month,” Marcus says. It also documents racism and white supremacy. “If we want to understand the impact of hundreds of years of prejudice, this is one of the resources that will help us do that.”

At the same time — and now matter how large the Givens Collection is or becomes — the collection also represents a loss, Marcus says.

“For hundreds of years it was illegal to teach Black people to read and write in the United States,” she says. “There are more individuals than we can count who should have been writers and poets and playwrights and theologians and chemists and all of the things that might have landed their papers in an archive. Instead, they were enslaved.”

McClintock says she didn’t know much about her history until she came to work in the Givens Collection. For her, February is a time to reflect on Black history but also “a month of reprieve” after being “inundated with racism all the time.” She will strive to decompress, to practice self care, and to look for inspiring moments in Black poetry and art.