By Allison Campbell-Jensen

In 1948, Hubert H. Humphrey captured national attention with a galvanizing speech on civil rights at the Democratic National Convention. Many accounts of his career begin with this event. But Samuel G. Freedman, a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism, wants the book he is writing to end with it.

In covering Humphrey’s early life and career, Freedman is focusing on his leadership of anti-racism and antisemitism efforts during and right after World War II. His book will also delve into the experiences of Black and Jewish communities in Minneapolis at that time. “That is what led me to want to burrow into 18 years’ worth of American Jewish World, from 1930 to 1948,” Freedman says.

Now the Minneapolis-based newspaper is being digitized by the Upper Midwest Jewish Archives at the Libraries. Archivist Kate Dietrick says that having it “available online for people across the Midwest, indeed across the world, to page through or even keyword search from the comfort of their own homes — this is where back issues of a community newspaper should live.”

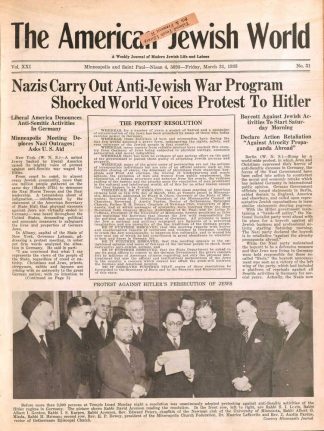

American Jewish World is a community newspaper that also embodies the World in its name, with images such as a group of religious leaders in 1933 protesting Hitler’s persecution of European Jewry.

Dietrick’s project ultimately will digitize issues from 1915 to 2007; currently, they have 1915-1933 and 1948-1958 digitized and available in UMedia.

Valuable point of view

“To get a really granular sense of what Jewish life was in Minneapolis back in the ’30s and ’40s, which is the period I’m focused on, you can’t depend on the Star and the Tribune, and the Pioneer Press,” Freedman says. “Minority communities of all sorts barely got covered. To be able to read in incredible detail the doings of the Jewish community in Minneapolis, I can’t think of a better resource than the American Jewish World.” With it, Freedman can track information he can’t get anywhere else, such as which Jewish groups Humphrey was speaking to, how many ads he bought, and how he was regarded as an ally, “to use the current term.”

American Jewish World also was essential in researching the 2017 exhibit “A Campus Divided: Progressives, Anticommunists, Racism and Antisemitism at the University of Minnesota 1930-1942,” says Professor Emeritus Riv-Ellen Prell. Before the exhibit, she had to visit the newspaper office to peruse back issues.

“We were committed to telling the story from as many perspectives as we could. It was difficult to find the perspectives of the African American community and the Jewish community beyond the campus about what was happening at the University of Minnesota — only their newspapers [the American Jewish World and the Spokesman] offered that.”

In 1935, the Nazi ambassador to the United States was invited to campus by the German Department. Prell learned some of the story from the Minnesota Daily — and the untold story from American Jewish World.

“Every Friday for weeks, the paper covered what happened on campus, in both Minneapolis and St. Paul, who was involved in the protest, and the feelings of vulnerability and anxiety expressed by the journalists who covered the story,” who knew what was happening to Jewish people in Europe, Prell says. “I was riveted by every issue, but I was also covered in shreds of newsprint and dust from volumes that were 80 years old.”

Donations that led to digitization

“To get a really granular sense of what Jewish life was in Minneapolis back in the ’30s and ’40s … you can’t depend on the Star and the Tribune, and the Pioneer Press,”

—Samuel J. Freedman, professor, Columbia School of Journalism

Mordecai Specktor is the editor of the American Jewish World, which is still publishing in print and online. He is a partner, along with Joel Kramer, former editor and publisher of the Minneapolis Star Tribune, and Steven Greenberg, who wrote the song “Funkytown,” in its owner, Minnesota Jewish Media, LLC.

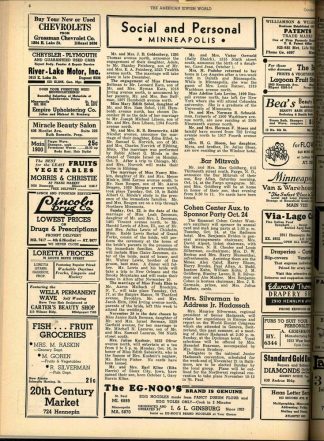

Specktor notes that in American Jewish World, researchers also can find family history and social news in birth announcements, reports of whose relatives were visiting from Duluth, or the names of those gathered for a bridge luncheon. “It’s the hyperlocal approach, which has come back to community journalism,” Specktor says.

That hyperlocal approach allows Freedman to track the doings of Sam Scheiner, a lawyer barred from white-shoe law firms because he was Jewish, who became a “one-man anti-defamation office” and was very influential with Humphrey. From playing jazz piano to support himself, to the letters he wrote back from the Pacific theater in World War II, to keeping tabs on the Silver Shirts and their antisemitic activities, Scheiner was covered in the newspaper — and so fills out Freedman’s characterization of Humphrey.

Specktor recognized the value of past issues of American Jewish World — and that some were deteriorating. A couple of years ago, he decided to donate a set of bound volumes, which he and Dietrick loaded up in her car to take to the University.

Once the volumes were in-house, Dietrick began seeking ways to fund their digitization. Some of the paper is very fragile, she says, but fortunately the Libraries have expertise in conservation. Initially, she turned to crowd-sourcing the funding. After informing her advisory board and having word of mouth carry the news, donors gave generously before the campaign even took off. She had thought it would take a year to raise the amount needed. Instead, it took a month.

One donor is Katherine Tane, former executive director of the Jewish Historical Society of the Upper Midwest. When their society created exhibits, made a film about the North Side, or answered queries from authors, scholars, or family genealogists, “the American Jewish World was one of the first places you’d go.”

The newspaper has so much rich material, Tane says. “This was a group of people who needed to communicate with each other — who’s marrying who — and also understand the news of what was going on in the community and around the world and how it relates back to themselves. It was a chronicle of what was on people’s minds.” To preserve this resource and make it available, she donated to support the digitization in honor of Linda and Len Schloff’s wedding year. Linda Schloff was instrumental in the early years of the archives that now reside at the University.

“Maybe in the wider world, ending up in the New York Times is a big deal,” Tane says. “Around here, you end up in the American Jewish World, it’s a big deal.”

Prell notes: “The fact that I can search this invaluable source anywhere I am in the world is great news. It will now be available, as it has not been before, to be used by scholars all over the world.”