Guest Blog by Gayle K. Brunelle, Professor Emeritus, California State University, Fullerton

The title page of the Dutch translation of Sir Walter Raleigh’s account of Guyana. Bell #1617 Ra.

The Guyanas, the coast of which has often been dubbed the “Wild Coast” since Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1595 visit to the Venezuelan region of the Guyanas, is the area of South America demarcated by the Orinoco River to the North, the Amazon to the South, and a series of massive mountain chains to the west. The Equator runs through the southern part of the region, which is tropical in climate and home to a huge chunk of the Amazon rain forest as well as some of the famous ancient flat-topped mountains known as tepui.

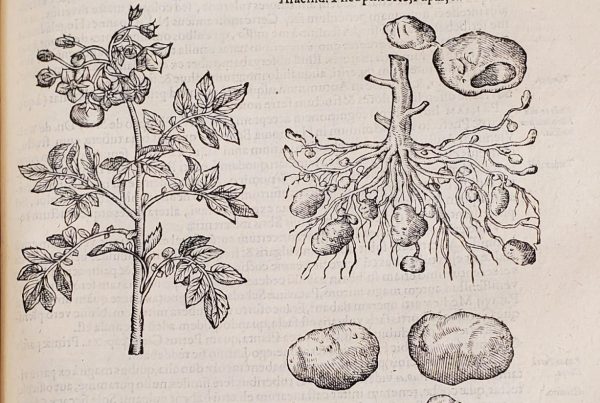

The Guyanas are now divided among Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and the French overseas department known as French Guiana. Sir Walter Raleigh sought to find El Dorado in the Venezuelan section of the Guyanas, but most Europeans who went there in the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries sought either to trade with the Native peoples or to establish plantations where they could cultivate sugar, tobacco, brazilwood and other tropical products in high demand in Europe.

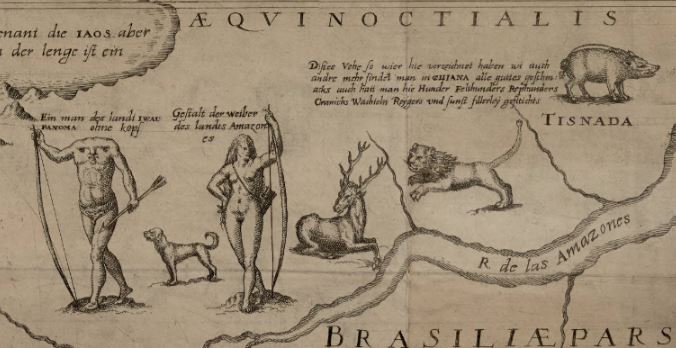

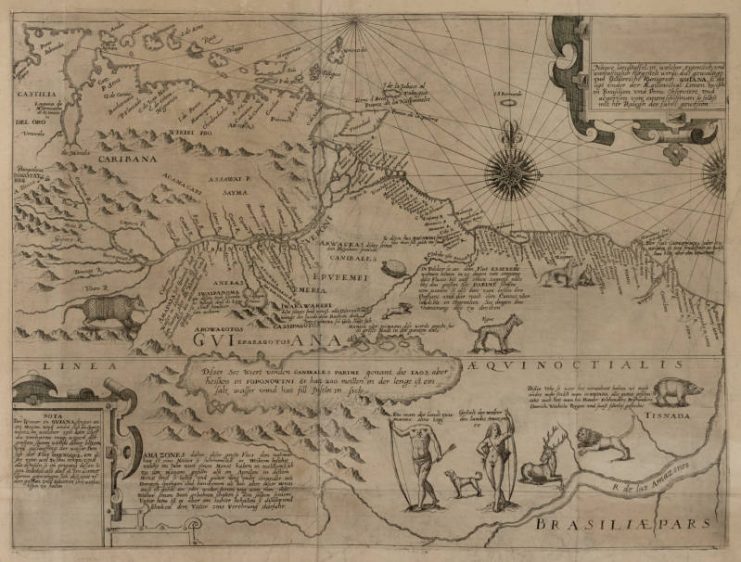

As the map below demonstrates, initially, in the minds of most Europeans, such as Sir Walter Raleigh, or the German creator of this map, Guyana denoted an exotic land filled with strange peoples and animals, a mélange of monstrous beings straight out of medieval bestiaries and actual observations of the flora, fauna, and inhabitants of the New World.

Map of Guyana in Theodor de Bry’s, Reisen im Occidentalischen Indien, vol. 3 (1590).

The coast was much better understood than the interior, primarily because it was a place of encounter, much more than settlement, until the close of the seventeenth century. Dutch, English and French explorers, traders, and planters came to the Guyanas, in large part because the rest of South America was under Spanish or Portuguese control. The “Wild Coast” was the only place where non-Iberians could trade with the Native Arawak and Carib peoples with little interference. These peoples, while willing to trade, were decidedly less enthusiastic about the establishment of plantations, however, and the European presence in the Guyanas remained tenuous for the first century of contact.

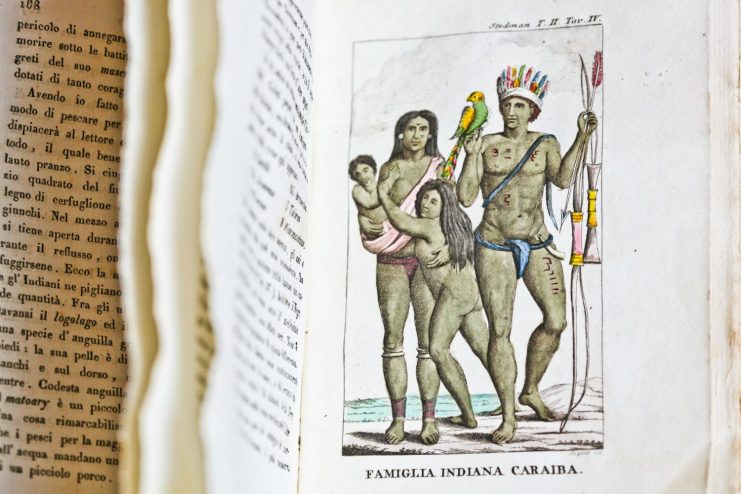

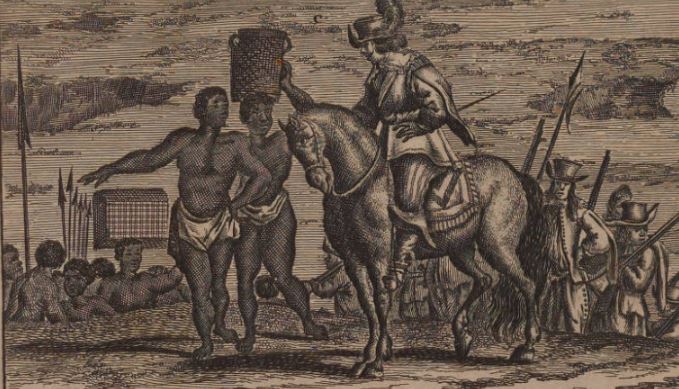

From the Italian translation of John Gabriel Stedman’s description of the “Indians” of Guiana. Bell # 1818 St (b). Photo by Natasha D’Schommer.

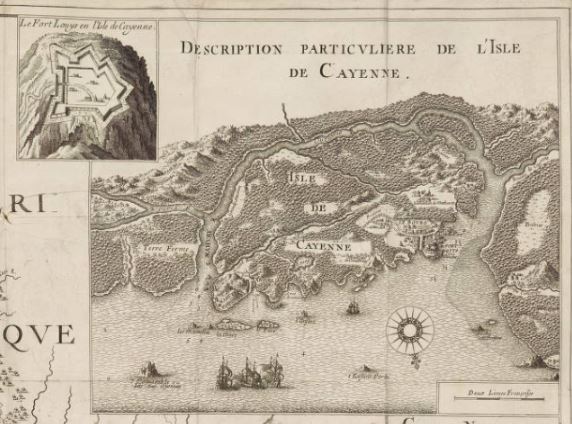

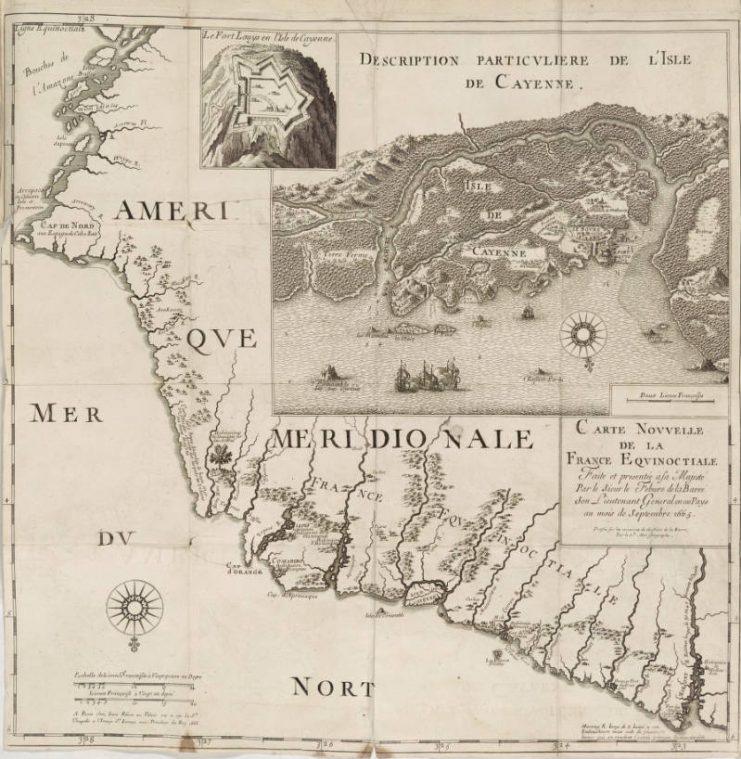

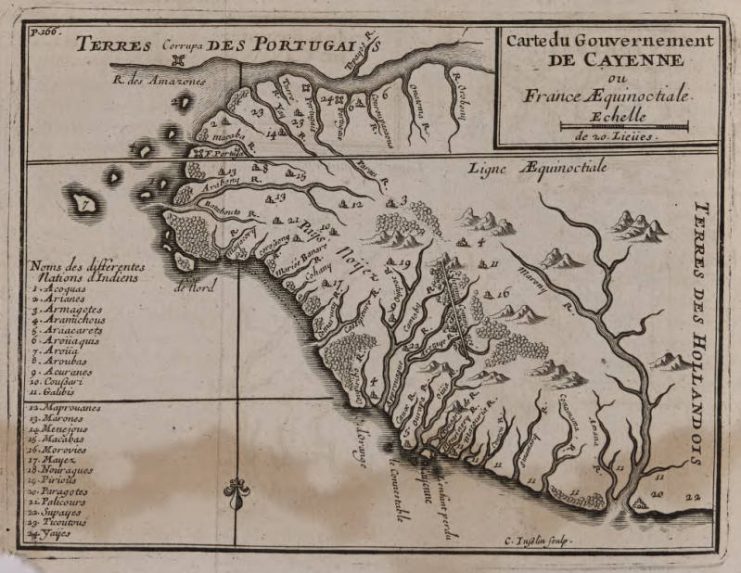

The French staked their claim on the “island” of Cayenne, because it had a small highland where a defensible fort could be constructed and was cut off from the mainland by a series of waterways (long since drained). Cayenne changed hands several times in the seventeenth century, as the French struggled to establish a permanent settlement in the face of the hostility of the Native Galibí people, as well as the Dutch and the English who had small colonies in Suriname. When the map below was created, the French had established a commercial company to sponsor a colony in “la France équinoctiale.” As happened several times before, the company went bankrupt and the French colonists mostly fled to Suriname or the Antilles.

Joseph-Antoine Lefebvre de la Barre, Carte Nouvelle de la France Equinoctiale (Paris, 1666).

The French persisted, however, and created, on paper at least, a “gouvernement” at Cayenne, designated the seat of France’s claims in the Guyanas. It was actually the Jesuits who in 1652 founded a mission, Loyola, and the first permanent and successful French plantation in la Guyane française, at Rémire rather than Cayenne. Despite the struggles of the French to maintain their colonies in Guyana, by the second half of the seventeenth century they imagined the region, or at least the coast, as a place for settled colonies resembling those in the Antilles, rather than simply as a place for trade.

François Froger, Relation d’un voyage fait en 1695, 1696, & 1697 (Paris, 1700). Bell # 1700 Fr.

In this respect, the Guyanas, in the French imagination, followed a trajectory not unlike that of their settlements in Québec. In French Guiana, however, the French colonists followed a plantation model and imported increasing numbers of African slaves rather than, as in Canada, using European indentured servants for their labor force.

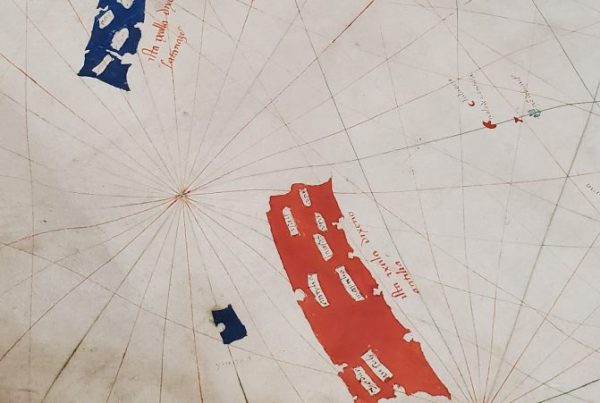

Excerpt from a scene near a fort at the Amazon delta in an account by Arnoldus Montanus. Bell #1673 fMo.

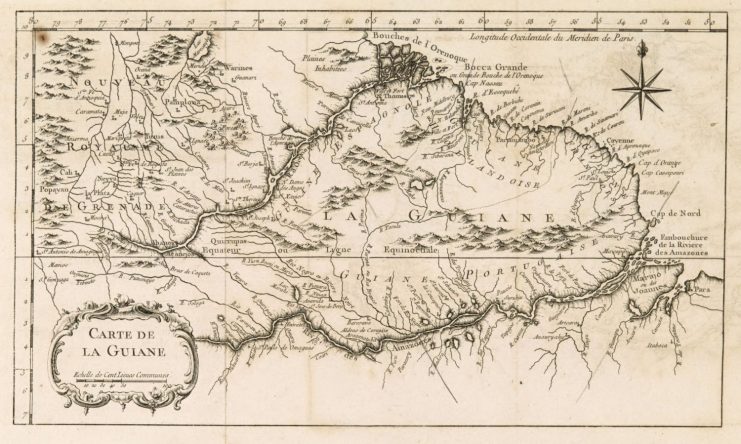

Thus, as our final map shows, by the opening of the 18th century, Europeans had explored the region sufficiently to understand better its geography. Gone are the imaginary creatures, and the French fort and settlement at Cayenne are clearly marked. Moreover, the French have staked their claim to the territory north of the Amazon and south of the Maroni, after which Dutch-controlled Suriname began. But if we compare the first and last maps here, we can also see that the essential geographical unity of the region remained consistent – bounded by the Orinoco and Amazon, and separated by mountains from the rest of the interior.

Jacques Nicolas Bellin, Carte de la Guiane (Paris, 1763). Bell #1763 Be.