By Allison Campbell-Jensen

Commemorating the centennial of women gaining the right to vote was her first idea, says Kate Dietrick, Archivist of the Upper Midwest Jewish Archives. But then she realized she had nothing in her collection to mark that milestone. Yet her collection and others at the Libraries have a wealth of materials on women at work, defined broadly.

When she suggested the topic of women and work to her colleagues in Archives & Special Collections, two offered to join her: Linnea Anderson, Archivist of the Social Welfare History Archives, and Caitlin Marineau, Assistant Curator for the Children’s Literature Research Collections.

“A Woman’s Place: Women and Work” opened Nov. 11, 2019 in Elmer L. Andersen Library and closed March 6, 2020.

Dietrick, Anderson, and Marineau decided at the start of this labor-intensive project that they wanted it to have a second life as an online exhibit. After it was taken down, they didn’t return all the materials immediately but instead had a student worker scan them all. To fully accomplish the online presence, however, they needed one more piece.

First steps

But assembling the exhibit came first. The trio of exhibit co-curators could have taken years to mine the special collections, Dietrick says; instead, they went to those in charge of collections to find out which materials about women and work were outstanding. They asked, she says: “What is the first thing that pops to your mind?”

Once materials had been pulled from collections, they had the mental effort of organizing them into categories, each of which would have its own display area. Childcare was one.

“If you have women in the workforce and these women have children and historically, women have been in charge of the children, what happens then?” Dietrick says.

The Social Welfare History Archives had a brochure about setting up a suitable childcare center, for instance. The University Archives held the history of setting up the U’s Child Development Center, Dietrick says, “and how contentious that was.” And the conversations about whether to shut it down continue, she says.

Reflecting heat

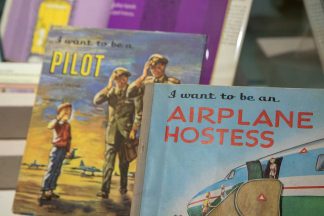

Marineau found a heated exchange of letters in the papers of author Carla Greene. She wrote books for children from the 1950s through the 1970s, among them “I Want to be a Pilot” and “I Want to be an Airline Hostess.”

In 1973, Greene received a letter from an 18-year-old college student, Leslie Austin, who was interested in child psychology. Austin wrote about the pilot and airline hostess books: “I was appalled. The stereotyping and blatant sexism … were unbelievable … the boy can learn about engines, radios, and weather, whereas the girl learns about how the pilot flies, and how to care for sick people, serve food, and help feed babies.”

In her response, Greene clearly was appalled by Austin’s “audacity.” She responded that she had based the books on government statistics of which gender held these jobs. And women who had done so-called men’s work during World War II were glad to “go back to their household chores.” She did note that in a more recent book about cowboys, she had included a cowgirl and a woman television director: “So you see I have not been waiting for you to enlighten me.”

In the physical exhibit, if students didn’t read Greene’s name in the descriptive placard or on Austin’s letter, they often assumed it was a man answering the student, Marineau says.

Women and volunteering

A favorite part of the exhibit for Dietrick concerns the volunteer efforts of women, about which she has a lot of materials.

“I’m fascinated because I want to know why they are volunteering,” she says. “Did they think of it as work? Did they think of it as social, as fun, as being an activist?” Materials from the American Council of Jewish Women showed that some of them were raising significant amounts of money for their causes.

At the exhibit, Dietrick met a woman who didn’t understand why her mother had been such a dedicated volunteer.

“Seeing it in that context of work, and how much work it was to volunteer, that it was an avenue for women who didn’t necessarily need a paycheck, but still wanted to exercise their minds, exercise their rights, and be socially active and activist — this woman thanked us,” Dietrick says. “‘I never really thought of my mom volunteering as doing something remarkable.’” Dietrick says she loved that realization which arose from viewing Unpaid & Unrecognized.

Eye-catching

A film from the University Archives, “University Secretary,” shown in Andersen captured people’s attention. “It essentially juxtaposes what a bad secretary would do — her hair would be loose, she’d be chewing gum, her desk would be messy — versus a good secretary,” Dietrick says, “whose hair is up, whose outfit is professional, who is not chewing gum, who organizes her desk and files.”

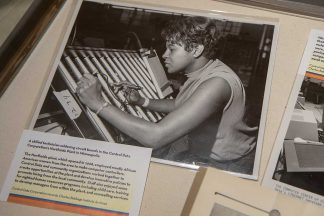

In the exhibit, the curators strove to include a diversity of voices. “Because women in the workforce cross all sorts of races, ethnicities, abilities, and socio-economic backgrounds,” Dietrick says. The exhibit includes memories from a formerly enslaved person, for instance, as well as materials about women working in factories, reports on sex work, and a list of female firsts.

Moving online

A skilled technician soldering circuit boards in the Control Data Corporation’s Northside Plant in Minneapolis, 1968.Charles Babbage Institute Archives.

From creative outlets to war work, children’s books to activism, “A Woman’s Place” covers a span of women’s experiences from the recent past. The final piece to moving all this online was Ashley Walker, a student in the M.L.I.S. program at the University of St. Catherine.

She had seen the exhibit before it came down, Dietrick says. “She essentially re-created our physical exhibit online,” she says. “It’s something we really wanted to do, to breathe life into this exhibit.” And to allow more people to see these perspectives on the world of women and work.