By Anne Good, Assistant Curator

When James Ford Bell provided the core collection of books to found this library back in 1953, his main interest was trade. He wrote, “Trade, to me, is an expression of the world’s economy of living. … Trade itself is basically a selfish interest. Trade knows no border, no kin, no breed, no loyalty of patriotism, or sentiment. Trade goes on regardless of wars, riots, and commotions. Trade seeks avenues of advantage even as between enemies. Always it searches for that which serves its interests best.” [In James Ford Bell and His Books (1993), 47.]

Walter Bigges, A summarie and true discourse of Sir Frances Drakes VVest Indian voyage (Bell # 1589 Bi); one of the first books purchased by Mr. Bell for the library.

This fascinating characterization of trade as an impersonal force would be questioned by many historians today. Indeed, the kind of economic and political historical research that was representative of scholarly practice in the mid-twentieth century is rarely carried out now. Works of social, cultural, and intellectual history are much more common, perhaps expressing the changing interests of the wider public in the twenty-first century.

But Mr. Bell’s books, and the major collection that grew from the seed he planted, continue to be relevant and exciting in this cultural shift. Materials that were once mined for the purposes of purely economic history are now reconsidered to yield new perspectives on life in the premodern world.

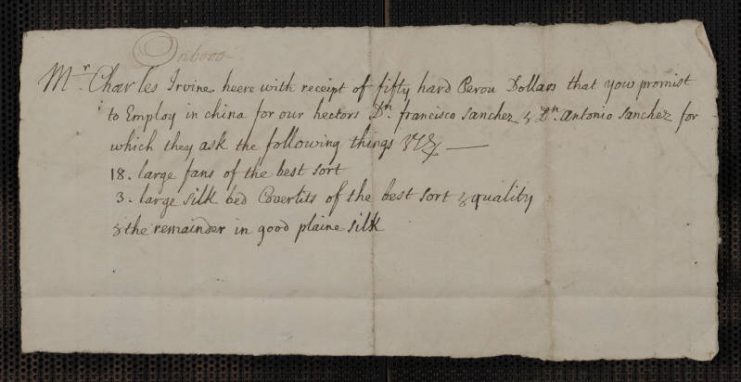

Instructions for cloth purchases in the records of Charles Irvine, a Scottish merchant working for the Swedish East India Company in the 18th century.

In recent months, as I have been learning the collection and thinking about changes in historical research practices, I have been intrigued by various items on cloth that I have discovered. Cloth was, of course, a major trade commodity in the early modern world. Cloth was traded across the world, and different types of textiles were produced by different cultures around the world as well. Cloth manufacturing became one of the engines of the revolutionary industrial developments of the eighteenth century. Cloth or textiles are certainly necessary to create clothes, and clothing can be a peculiar crux of personal and corporate identity. Finally, cloth is particularly tactile, and the Bell’s collection has several items for the emerging field of sensory history.

First, consider that the European ships of various sizes that began traveling the world’s oceans with increasing volume and frequency from the 1450s onwards used yards upon yards of cloth for sails.

A ship in full sail, included on one of the maps of Jan Huyghen van Linschoten’s travels (Bell # 1638 fLi).

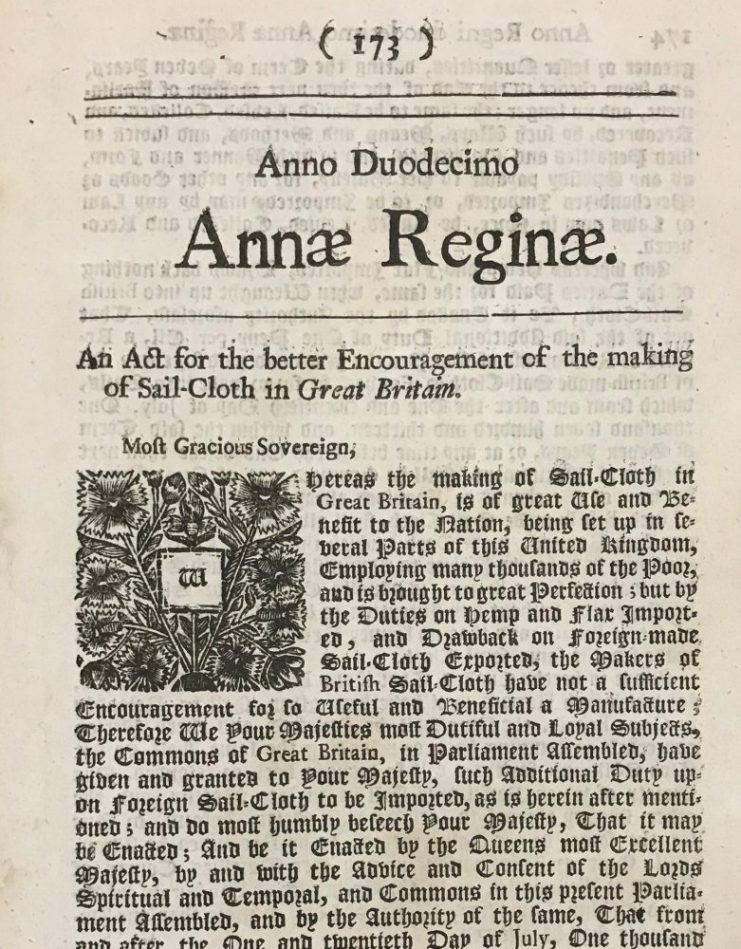

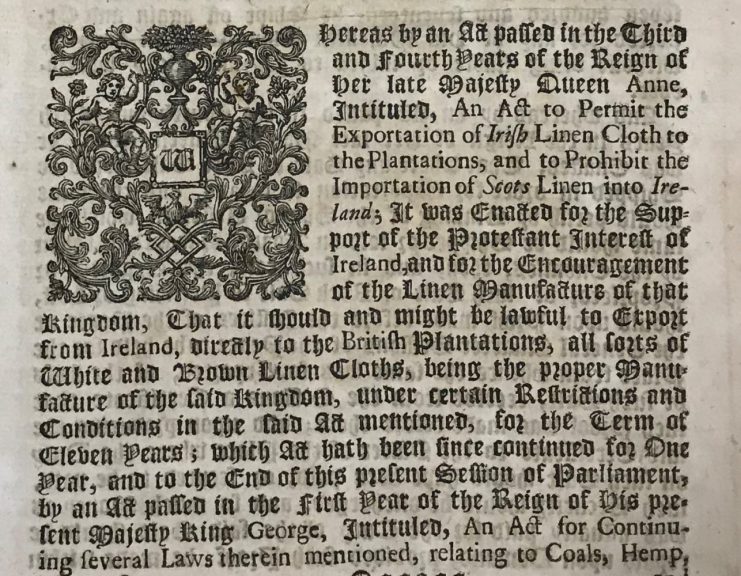

And because cloth was so important, both for ships and people, governments made laws all the time to try to protect both manufacturing and selling this product to gain the greatest benefits for their own nations. Representative examples are the two laws below proclaimed and published in Britain under Queen Anne (1702-14) and King George I (1714-25), respectively.

Under Queen Anne, “An Act for the better Encouragement of the making of Sail-Cloth in Great Britain” – published in 1713 (Call # 1713 G.B. 3) – called for an increased duty on canvas imported from abroad, usually called “Hollands Duck or Vitry Canvas.” And, at the same time, the act offered a monetary reward for manufacturers of sail cloth in Great Britain or Ireland.

“An Act for the better Encouragement of the making of Sail-Cloth in Great Britain” (Bell # 1713 G.B. 3).

Under King George I, in 1717, “An Act for Continuing the Liberty of Exporting Irish Linen-Cloth to the British Plantations in America, Duty-free; and for the more effectual Discovery of and Prosecuting such as shall unlawfully Export Wooll and Woollen Manufacture from Ireland…” (Call # 1717 G.B. 1) is focused on encouraging the Irish production of white and brown linen cloth for export to the British colonies abroad, while at the same time essentially forcing them to sell their woolen cloth only domestically or to England and Wales.

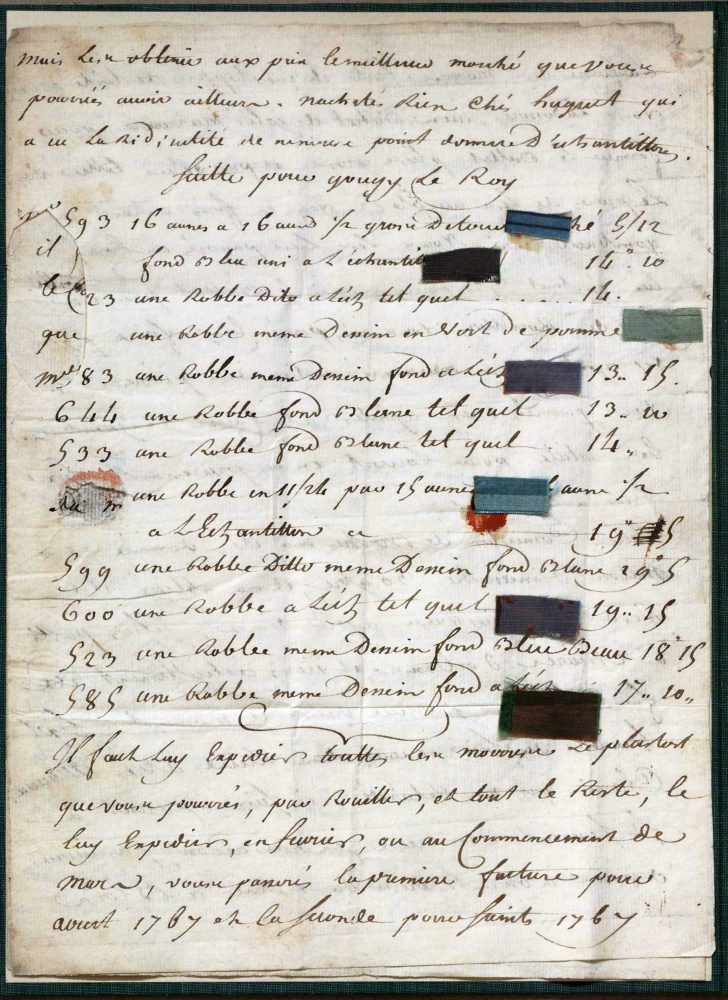

Numerous merchant records in the Bell’s collection also refer to the cloth trade. Most beautiful among these records are those that include cloth samples. The merchants were interested in evaluating quality and choosing patterns, and because these records still exist, we have the pleasure of a tactile connection with history. The first example below is a letter between two French merchants in 1766, one in Orleans and the other in Lyon, discussing prices and fabric dimensions, and including seven very small silk samples.

Silk samples in a letter from Mr. Carrel in Orleans to Mr. Carrel et Cie in Lyon in 1766 (Bell # 1766 Car).

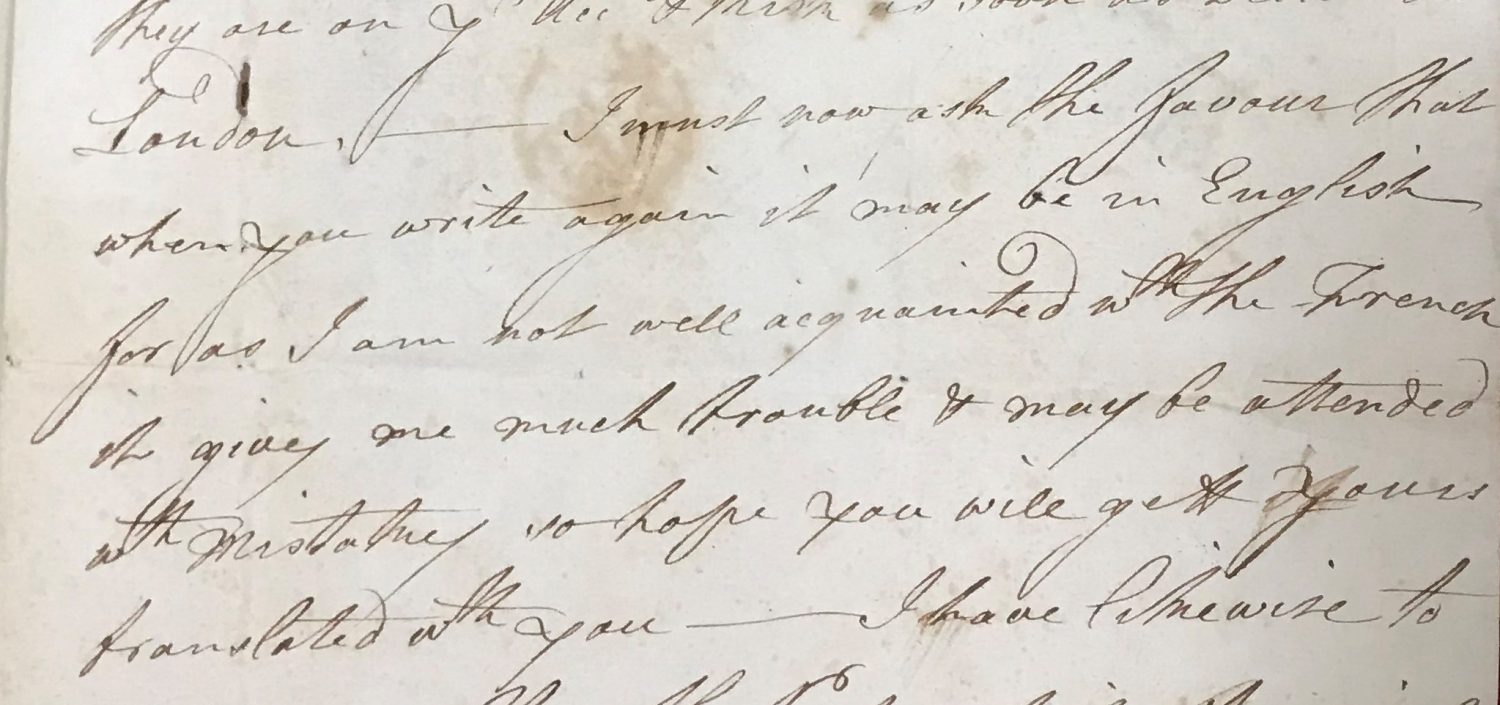

The second example is also from 1766, between William Carpenter, a woolens manufacturer in Salisbury (Sarum), England, and John DeWolf, a buyer in Antwerp. Included in this letter are 18 samples, with possibly two more now missing. They range in color: mostly gray, mixed-gray, and white, but also including stripes and vibrant red and dark green. Mr. Carpenter also notes that the prices he includes are for payment with “ready Money.”

Somewhat humorously, Mr. Carpenter also has this request for Mr. DeWolf: “I must now ask the favour that when you write again it may be in English for as I am not well acquainted with the French it gives me much trouble and may be attended with mistakes so hope you will gett yours translated with you.”

Europeans encountered new types of textiles in the wider world, and they commented extensively on the clothes worn in other cultures, following the lead of Herodotus. While animal hides provided the materials for clothing in several cultures, weaving was not peculiar to Europe and the different fibers used were of great interest.

Greenlandic Inuit in sealskin suits and a Dutchman in chaps juxtaposed on a Hendrick Doncker map (Bell # 1661 oDo).

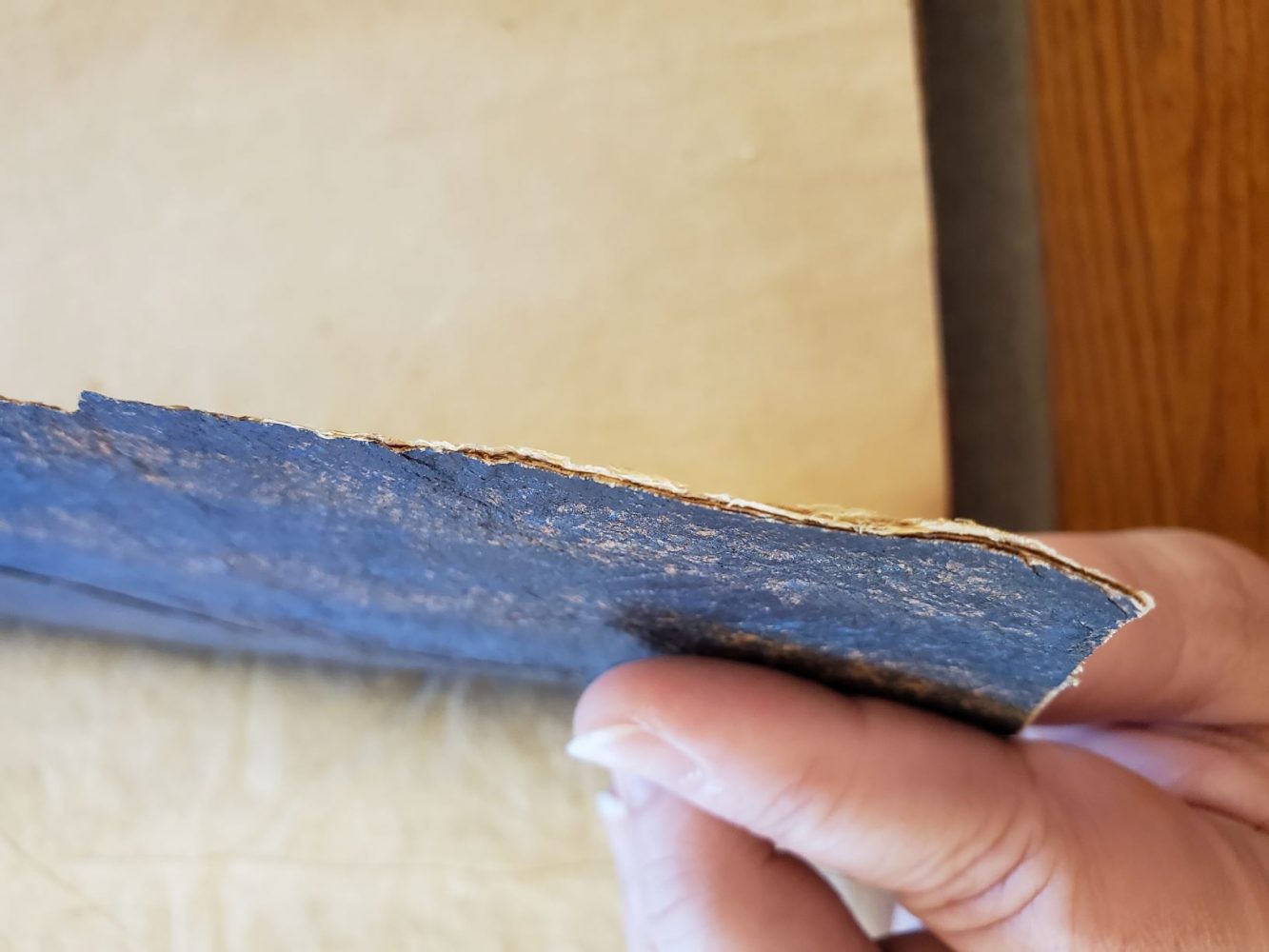

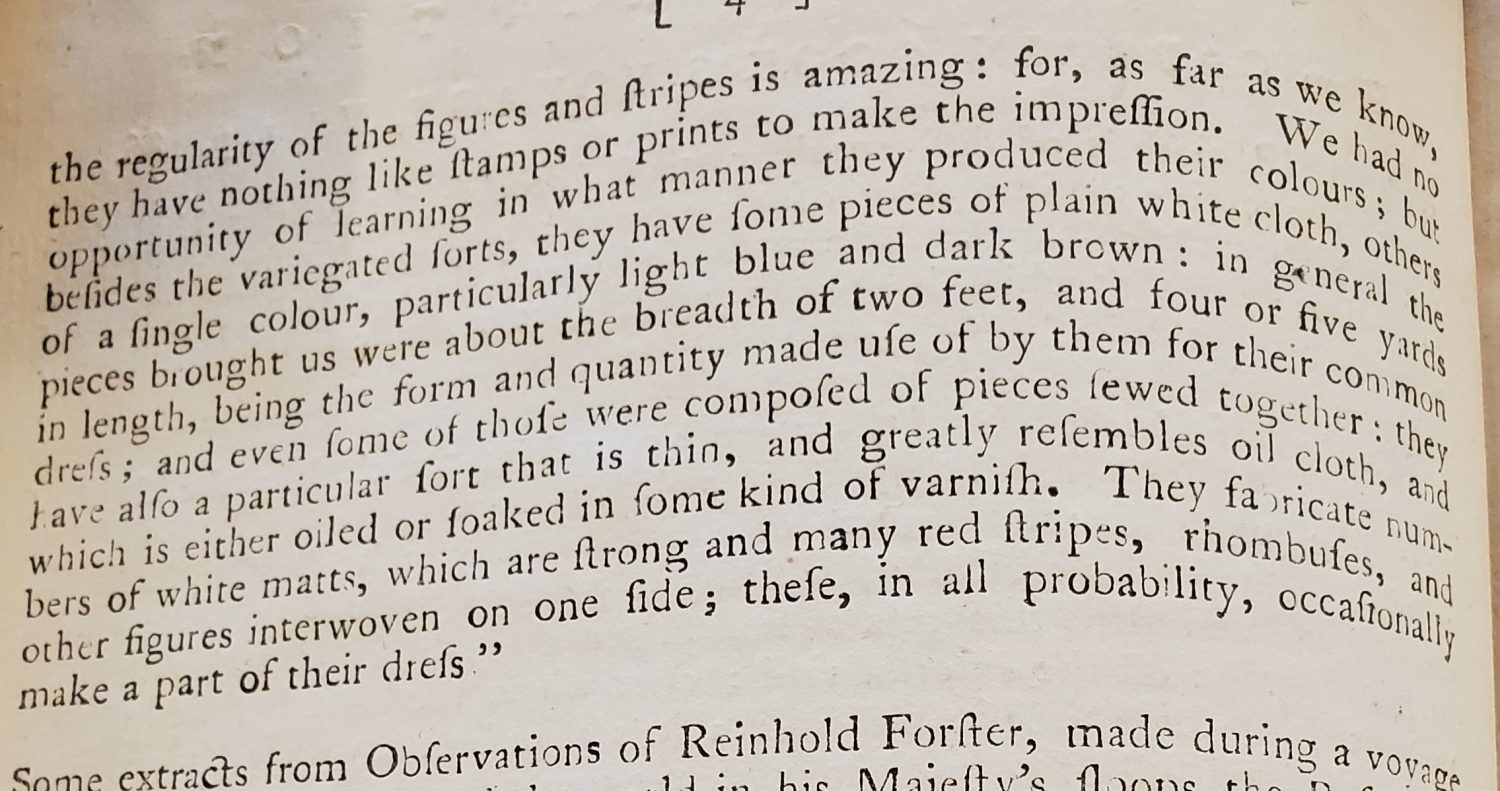

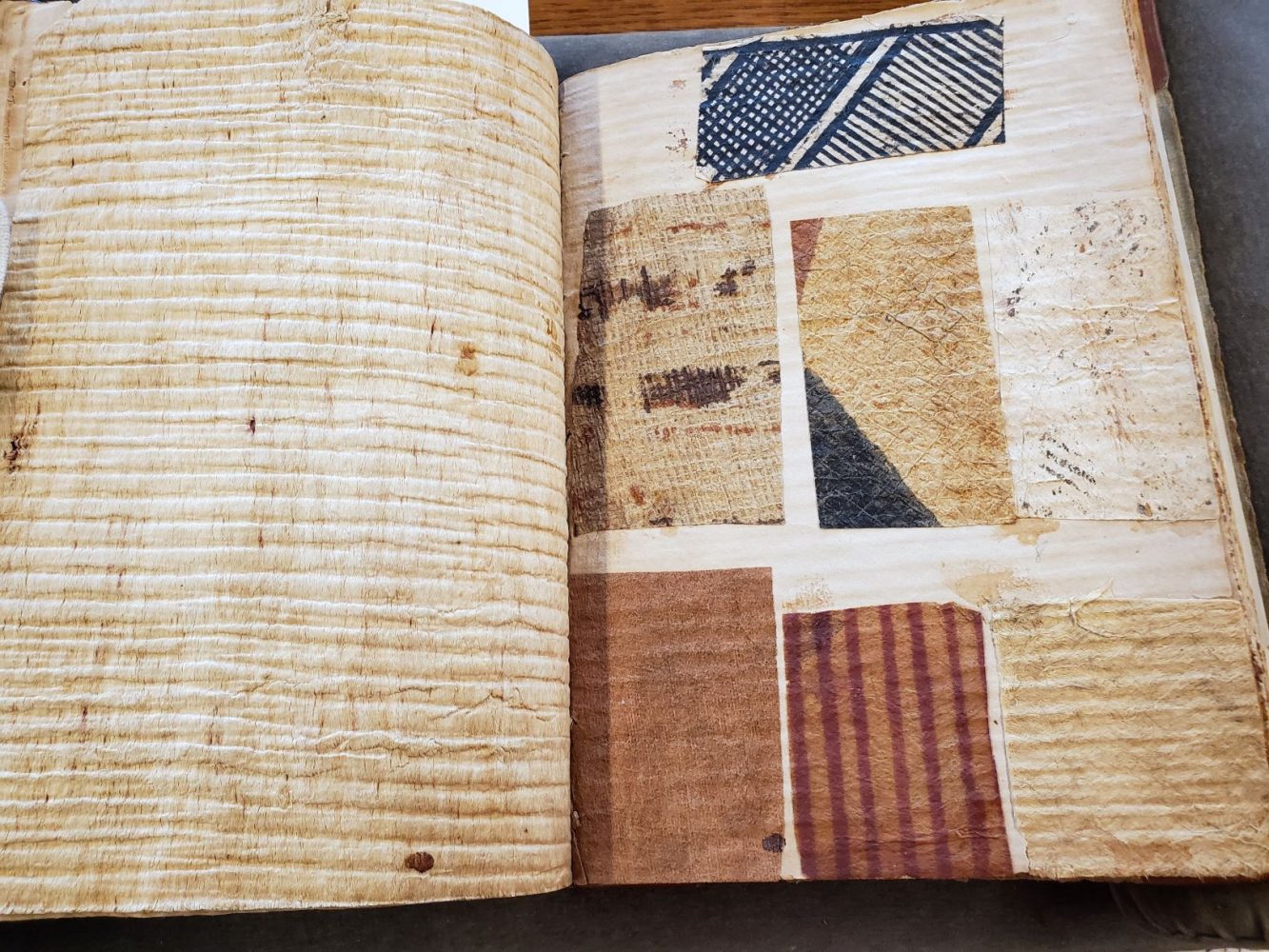

Surely one of the most fascinating items in the Bell’s collection is a book of textile samples – mainly bark cloth – gathered in the South Pacific during the voyages of Captain Cook. The textiles are accompanied by descriptive accounts of how the cloth was made or acquired, gathered by the compiler from various unnamed seamen, as well as the more famous published writings of Reinhold Forster. Although the book bears some resemblance to pattern books displayed by merchants, from which customers could make purchases, these items were not being offered for sale, or at least not on a large scale. Instead, they seem to be offered as tangible evidence for the eyewitness accounts.

Bark cloth from “A catalogue of the different specimens of cloth collected in the three voyages of Captain Cook, to the Southern Hemisphere” (Bell # 1787 Ca).

Though bark cloth remained a mainly local commodity, other textiles were indeed becoming increasingly important trade goods worldwide in the 18th century. One of the trade relations of that era that had far-reaching consequences was that between India and England. Textiles made from silk, cotton and jute were manufactured in India and exported to England throughout the 18th century. It was only in the 19th century that the British turned to mostly extracting raw materials from India, manufacturing the cloth in England, and then selling the finished products cheaply, but in great quantities, back in India. This virtually destroyed cloth manufacturing in India.

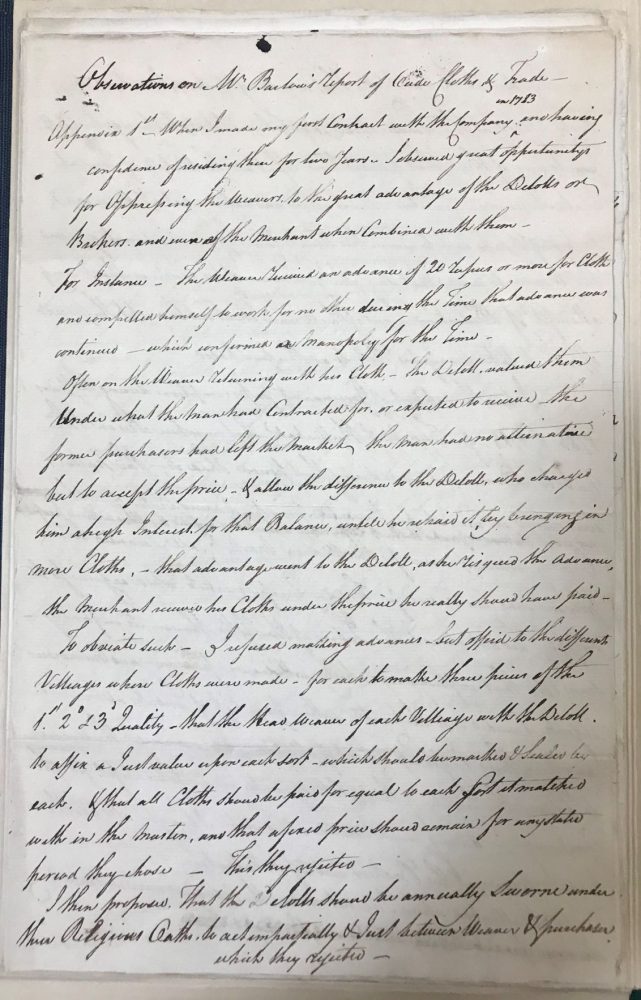

The letter below is from an agent of the East India Company, John Pinred Scott, dated to 1788, but referring to events about four years earlier. Scott was active in the rich province of Awadh (historically spelled Oude or Oudh), where the East India Company was already deeply entrenched and interfering with the policies of local rulers. Scott discusses plans he tried to implement that he claims would have given the weavers more freedom in how they sold their cloths, which the elites strongly resisted. Scott also defends actions he took to have cloth prepared for European markets, rather than just for local consumers. It is unclear here if he is responding to accusations of lessening Company profits, or causing shortages in Oude – he denies both.

British East India Company Agent discusses attempts to change the flow of transactions between weavers and their backers in the region of Oude. (Bell # 1788 fEa)

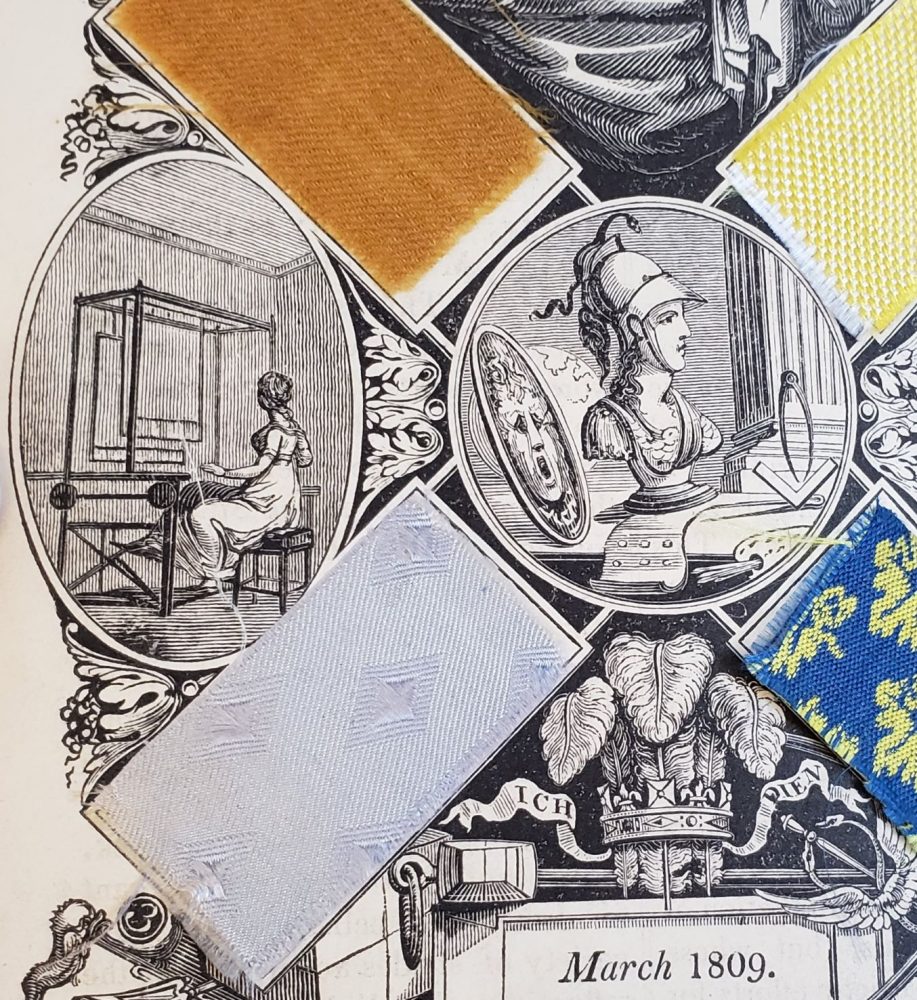

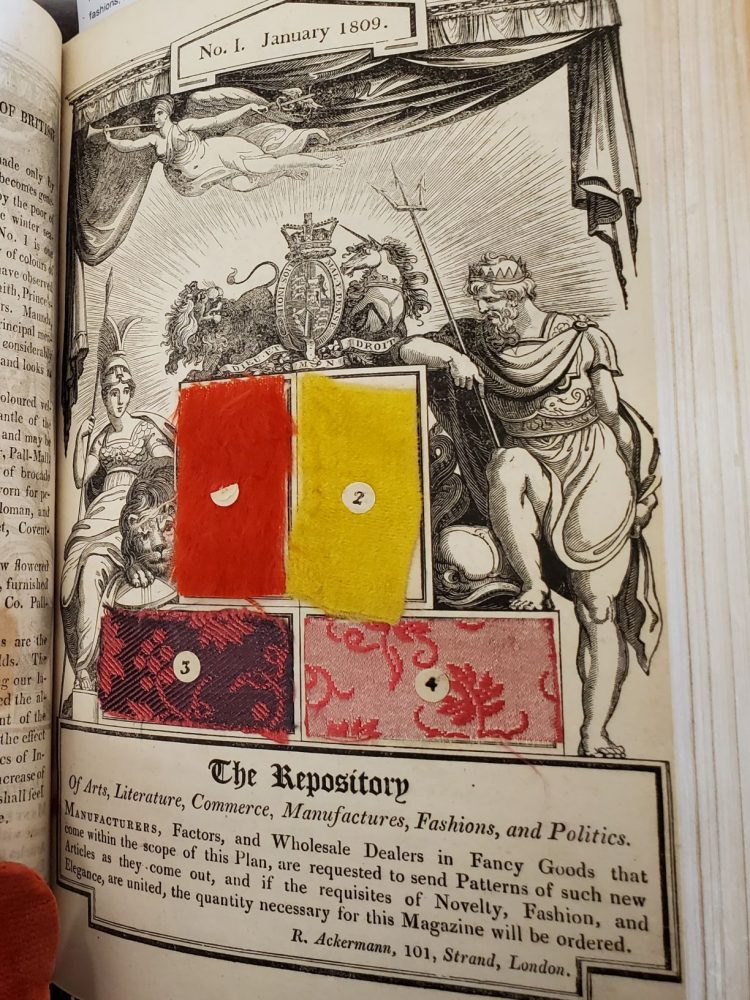

My final selections come from The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, Etc. (1809-1814), a British publication that showcased consumer goods and reflected on arts and literature for the leisure time of well-to-do, but not necessarily noble people. Each issue included fashion plates, as well actual cloth samples, and details of where the fabrics might be found and purchased.

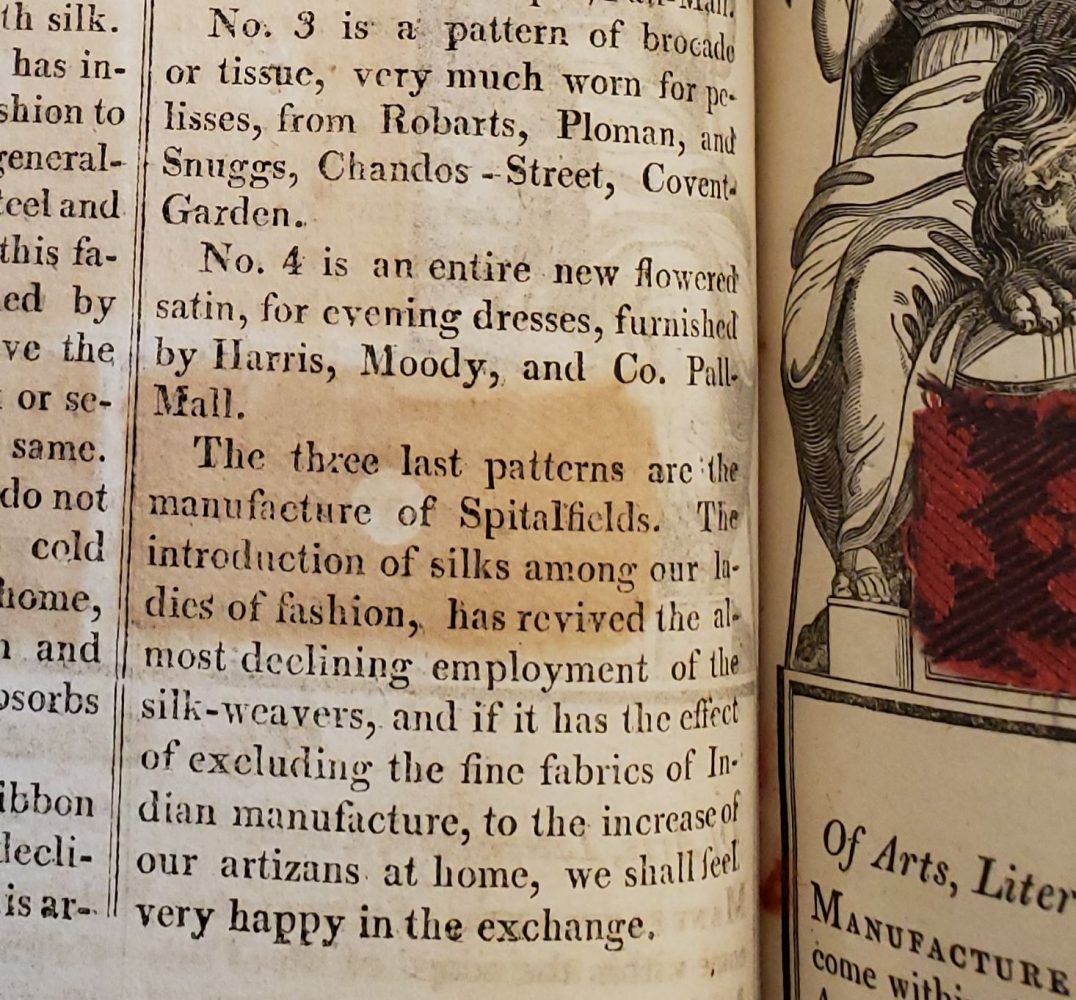

In his explanation of these samples, editor R. Ackermann seems to be reflecting anxieties about globalization in his own day. From his perspective, Indian or Persian textiles were competition for British products. He mentions that, though the cloth industry has declined greatly in Coventry, manufacture of sample number one (the flame-colored material in the second set of swatches) will keep the poor employed through the winter season. Likewise, in several issues he mentions the plight of silk weavers in Spitalfields.

Here the last three swatches come from silks to be made in Spitalfields, where silk-weavers are out of work. The editor expresses hope that the quality of these silks will push Indian textiles out of the market

How to wear British-made cloth. Ackermann’s Repository may be found in the Rare Books Collection at Call # 050 R299.

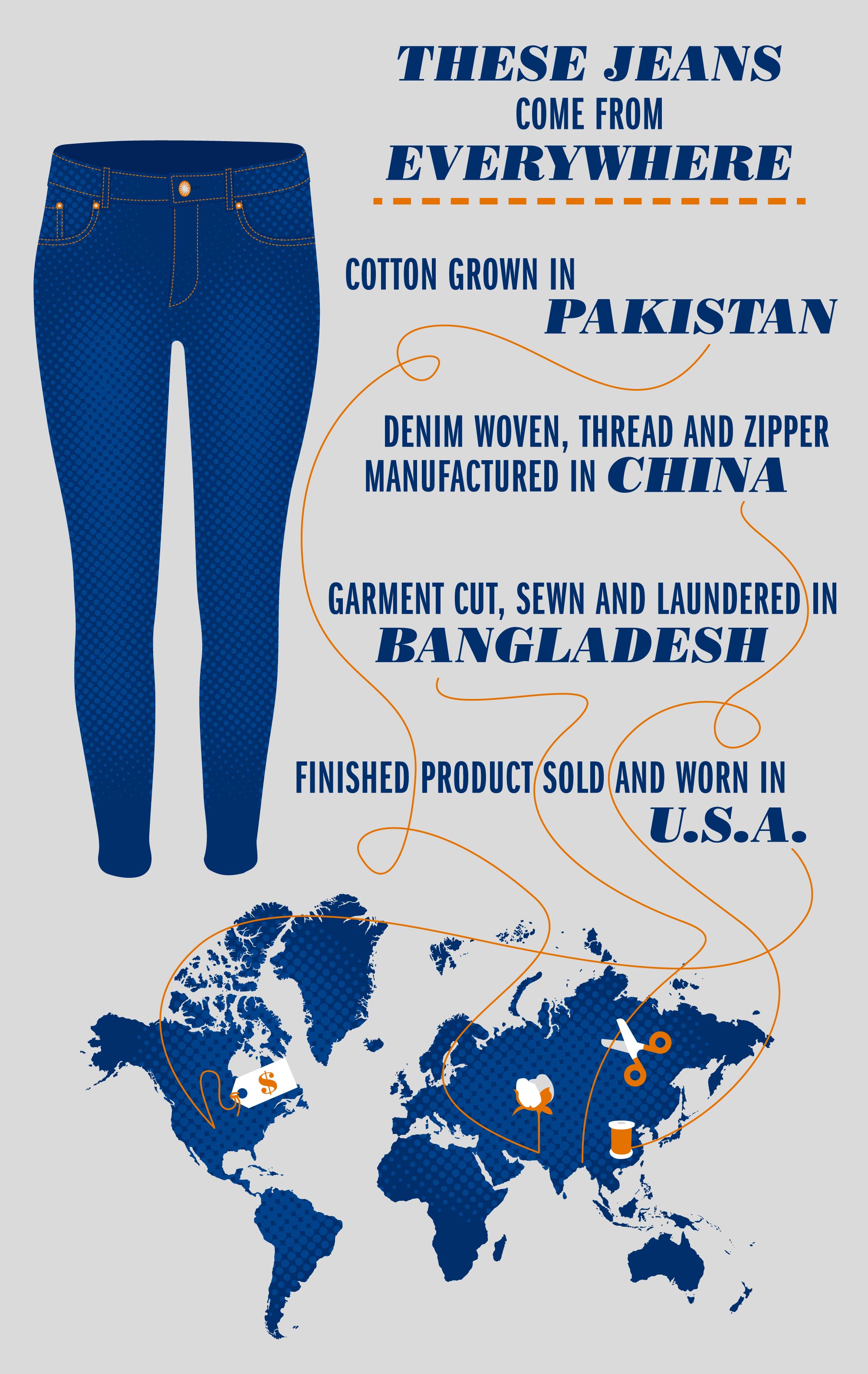

Textile production and clothing manufacturing have become increasingly huge businesses in the modern world. Today, these industries are fully globalized. When I taught World Geography at Reinhardt University, I had my students read Where Am I Wearing? A Global Tour to the Countries, Factories, and People that Make Our Clothes by journalist Kelsey Timmerman. One of the exercises Timmerman proposes is to make a spreadsheet of all the clothing items in your closet and where they were made. This in itself can be pretty fascinating, but Timmerman’s reporting on the lives of garment workers in Honduras, Bangladesh, China and Vietnam is incredibly eye-opening. In Bangladesh, for example, jobs in the textile industry that North Americans would consider exhausting, not worth the pay, and indeed unsafe, may well be fueling a revolution in the status of women.

Image from: https://shenglufashion.com/2018/09/04/textile-and-apparel-made-in-the-world/

Such an interesting read Anne, thank you!

The Costume Society of America will have their 2022 convention in Minneapolis. Your research would be a fantastic presentation.