By Allison Campbell-Jensen

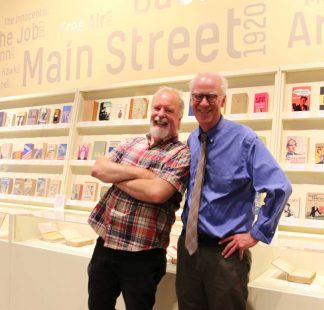

The power of partnership, the depth of one of the University of Minnesota Libraries’ collections, and the impact of a well-wrought exhibition were all demonstrated by a recent visit to “Sinclair Lewis: 100 Years of ‘Main Street’” at the Minnesota History Center. Tim Johnson, Curator of Special Collections and Rare Books, was invited to tour the exhibit with its curator Pat Coleman.

This is Coleman’s final exhibition before he retires from his position as Acquisitions Librarian at the Minnesota Historical Society in early August.

“It’s his capstone,” Johnson says.

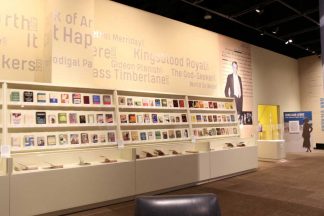

Outstanding among the displays — which include Lewis’s Nobel Prize medal on loan from Yale University, clips from movies based on his books, and correspondence with his editor — is a wall of books.

Among those books are 133 that the Libraries lent from its Rare Books collection to this exhibit.

Partners in history

In an interview following the tour, Johnson noted that the University Libraries and the Historical Society enjoy a collaborative relationship — a partnership. “There’s been a long-standing agreement, for instance, that the Minnesota Historical Society will have first option on anything related to Minnesota literature, Minnesota history, any aspect related to the state of Minnesota,” Johnson says. “And in that regard, they are the principal library and archive of record, and we’re there to backstop them.”

As a result, the Libraries and the Historical Society are “two pillars of cultural memory” in the state, Johnson says. When Coleman was researching the exhibit, prior to the pandemic, he came to the Elmer L. Andersen Library’s reading room in the Wallin Center to explore the Sinclair Lewis Collection. “He was totally engaged with the material,” Johnson says, going through book after book, making notes, and taking photographs.

“It was wonderful for me to retrace Pat’s steps after he had made the selections and see those book jackets myself. They are really amazing.” He has known Coleman for a quarter-century and appreciates how the exhibit reflects Coleman’s knowledge of Sinclair Lewis, as well as his love for books and book arts.

Strength of the collection

“One of the things that marks this as a wonderful exhibit is that it makes me want to read more by and about Lewis. It extends that invitation.”

—Tim Johnson

The many editions of Lewis’s works on display include translations into other languages, as well as from different time periods, which can be revealing.

“You’ve got the artistic expressions, the jackets, but you’ve also got subtle clues or hints of how Lewis’s work is received and understood in other countries and what gets emphasized in the story,” Johnson says.

For the strength of the Sinclair Lewis collection, Johnson credits Raymond Shove, a professor in the U of M Library School. He acquired most of the first editions, as well as biographical and critical material in 1945, according to a catalog from a Lewis centenary exhibition in 1985.

“Shove corresponded with Lewis, who at that time was living in Duluth,” Johnson said. “Lewis sent numerous volumes to help build the collection, mostly foreign language translations.” Shove invited Lewis to the University Library to write in each novel something about its background and his current thoughts about them, but he replied he was too busy. “[B]ut in January 1946 he made an unexpected visit to the library ‘to write in the books.’” This likely resulted in some of the inscriptions exhibit visitors can see.

One of Johnson’s favorite parts of the book display is the section of editions of “It Can’t Happen Here,” a Lewis novel warning of the dangers of fascism in the United States. The cover of a Dutch edition features a large swastika; another pops the title in white type from a red banner; a recent version uses two strands of barbed wire. “It was re-published [in recent years] and became a best seller again,” he says. “I thought that in itself was an interesting phenomenon, to have a book published decades earlier resurface and speak to readers in such a powerful and contemporary way.”

Most resonant and meaningful, however, were the horizontally arrayed editions that had been inscribed by Lewis. Seeing so many of them with the University of Minnesota Libraries book plate, Sinclair Lewis Collection, made Johnson’s chest swell with a feeling akin to pride.

“That brought home to me how strong our collection is,” he says, “and why Pat reached out to us to partner with him on this Historical Society exhibition.”

Personal impact

Johnson noted that many people have seen Lewis as an angry man who disdained Minnesota or Midwestern small towns. “That gets blown out of the water entirely by this exhibition,” he says. “It’s clear how much Lewis appreciated growing up in that kind of setting in Sauk Centre.”

Another aspect of the exhibit that impressed Johnson was the evidence of how Lewis dominated American literature in the 1920s. Sales of “Main Street” were unexpectedly phenomenal and that success was followed by others. Several of his books were made into movies.

Thwarted twice from receiving the Pulitzer Prize, he turned it down the third time. When he received a phone call from a member of the Nobel Prize committee, Coleman related, Lewis said, “That’s not how you do a Swedish accent,” and proceeded to mimic how the person should sound — until he realized it was not a prank call.

Johnson exited the exhibition with a thirst to know more. “One of the things that marks this as a wonderful exhibit is that it makes me want to read more by and about Lewis. It extends that invitation.”