By Allison Campbell-Jensen

The Minneapolis’s City Hall clock tower contains more than clock works. For decades, it was home to the Municipal Information Library, a branch of the former Minneapolis Public Library. When this branch library’s doors closed, much of the materials including maps and atlases simply stayed behind them.

Recently rescuing some of the maps and atlases, in coordination with City Clerk staff, became a project for Ryan Mattke, Head of the John R. Borchert Map Library, and Ted Hathaway, Manager of Special Collections, Preservation, and Digitization for the Hennepin County Library. And that is just a start to returning the maps to usefulness.

Locating the maps

The Municipal Information Library was located in the clock tower largely for the benefit of city staff, although ordinary citizens could use it. It was a fairly active place at one time, Hathaway says. After the Hennepin County Government Center was completed in the mid-1970s, the Hennepin County Courts documents were moved from the clock tower to there. When in 2002 the Minneapolis City Council decided to close the Municipal Information Library, some collections went to the Central Library. In 2008, the Minneapolis Public Library system merged with Hennepin County Library.

“Much of that space went into stasis, which is kind of a fancy way of saying it was ignored,” Hathaway says. After a project to add the City’s aerial photographs to the University Libraries, the question of the remaining materials arose.

Says Mattke: “What else is in the clock tower archive that might be of interest to the map library?”

There were Sanborn Fire Insurance Company Atlases, richly colored guides which relayed a great deal about building materials and locations in large-scale maps.

“For Minneapolis, 1912 was the first comprehensive look at the city. The city had two sets of atlases, one they did not change — they did not paste any updates into it, it’s pristine — and one they did update through 1929 or even the early 1930s,” Mattke says of the works he rescued to be digitized. “Each set is eight volumes and came to the U in June.”

In addition, the City Clerk’s office made decisions based on their own records retention schedule, says Jessica Velie, City Records Manager for Minneapolis.

“We had identified a set of maps that were historically important and deserved long-term preservation,” she says. Her predecessor and her supervisor already had developed relationships with Mattke and Hathaway; both University Libraries and the Hennepin County Library digitize maps, making them more widely available and ensuring their long lives.

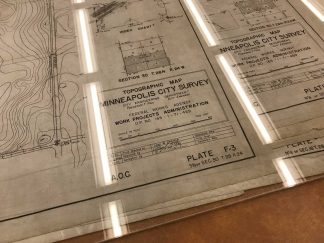

“The maps preserved in the clock tower, many of them are manuscript maps, produced by the engineering department, hand-drawn and hand-colored for zoning, density of population, location of streetlights,” and other details, Mattke says. He and Hathaway met in the clock tower a couple of years ago to divide up these maps, based on the scope of their collections.

Mattke and Hathaway spent a few days sorting through maps. “That worked out fairly well because Ryan was mainly interested in things that were citywide or metro-wide, which we already had a lot of. We were more interested in the things at the community level, like a neighborhood project or a street or a railroad going through an area,” Hathaway says.

“We’d literally unroll a map and say, ‘I’ll take this one’ or ‘You take that one.’”

Because these maps are official city records, the City Clerk’s office had to put forward a petition to the City Council to approve their transfer. “Our Council approved it, as did the City Clerk, then it went before the state archives and was approved by the State Archivist,” Velie says. “So everyone involved knew where the records were going and how they would be protected.”

The process began around 2018 and, from this excursion, more than 300 maps came to the University Libraries, Mattke says, and the preservation of those maps is almost complete.

Preservation

“The University of Minnesota has such an amazing library program in general and then the Map Library in particular is just topnotch. We know that the records, the atlases and maps, will be in a great repository, where they are looked after, where they have good preservation techniques.”

—Jessica Velie, City Records Manager for Minneapolis

Velie and colleague Christian Rummelhoff trundled the maps into a car and drove them over to the West Bank loading dock, where Mattke met them. The bulky rolls of maps, some in cases, then came under the care of preservation staff at the Libraries. First, they needed to be unrolled. Those on drafting cloth or canvas, says staffer Laurie Jedamus, were unrolled, laid down, put under Plexiglas, and then left for about a month to release their curl.

Paper or blueprint maps can be unrolled with the help of humidity. A bottom layer of plastic is lined with a cloth carefully dampened with distilled water. Then a layer of one-way permeable fabric is added and the rolled map is put on top, held open with weights. A top layer is added to protect it. Then Libraries staff check it several times during the day.

The different materials have personalities, Jedamus says. “It’s funny . … You can listen to the object and it tells you what [treatment] it is looking for.”

Once they are flattened, they can be protected with Mylar sheets — sitting inside an envelope of them, not adhered to them. Typically one side is left open so that maps can be removed. Once they are cataloged, they can be digitized.

Says Velie: “The University of Minnesota has such an amazing library program in general and then the Map Library in particular is just topnotch. We know that the records, the atlases and maps, will be in a great repository, where they are looked after, where they have good preservation techniques.”

Digitization

After cataloging, many of the maps will be digitized, making them more accessible to people, which is an important goal, Velie says.

“We’ve been pretty adamant about digitizing everything we can, especially in our Minnesota collection,” Mattke says. “A lot of times, we are the only institution that has those maps, the only one that has the resources to do the digitization.”

The digitized maps, held in U Media, can save those doing research a great deal of time. Someone doing research on a family farm in western Minnesota, Mattke says, may be very excited to find that maps from the late 1800s and early 1900s already are digitized.

“It’s the same for students, researchers, faculty, even on campus,” Mattke says. “When someone sends us a question or calls us or even stops by and says these are the resources I need, it’s great to be able to say, these seven are already digitized, here are the links, and we’ll get the other two scanned for you.” The opportunity is there to bring resources to a much broader audience.

So what was stored in a city branch library, rescued, and transferred to the University Libraries, completes and enlarges the circle of outreach by becoming available to anyone with online access.

“It’s not a competition,” Hathaway says. “It’s a collaboration and a desire to achieve a common goal: Preserving those things from the past that should be preserved and providing access to them.”

The Municipal Information Library (MIL) was the ‘brain child’ of Ervin Gaines, Director of the Mpls. Public Library and Tommy Thompson, City Coordinator, City of Minneapolis. A prototype existed in the City of Philadelphia; Mpls. staff visited that site and returned with recommendations. Under the supervision of Lyall Schwartzkopf, City Clerk, and the Minneapolis Building Commission, the bell tower was selected as the location. It was central, dormant and expandable. Library shelving was installed on each of three (possibly four) floors of the tower, office equipment was provided, elevator access was updated, original iron fixtures and brass work were retained. The collection was staffed by MPL personnel who reported to the City Clerk and to MPL while retaining MPL employee status.

The concept was ‘a hard sell’ at first, city employees questioned the need for a central reference collection re municipal government. Larry Irwin, Head of the Minneapolis Planning Department, was the first department head to agree to relinquish long held planning documents to the collection, thus setting the precedent. Other departments soon followed and city employees began to turn to the staff and collection for assistance.

Administratively, MIL was part of Special Services Department within the Minneapolis Public Library.

If memory serves me correctly, Ted Hathaway began his library career in that department!