By Allison Campbell-Jensen

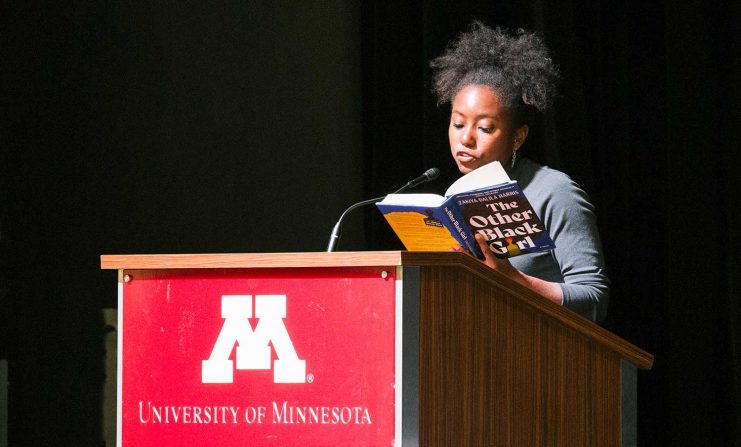

Best-selling author Zakiya Dalila Harris reads from her book, “The Other Black Girl,” at the April 27 NOMMO event.

Inquiring minds wanted to know more about author Zakiya Dalila Harris and her writing process at the recent Archie Givens Jr. NOMMO African American Speakers event, made possible by a grant from the Minneapolis Foundation.

The more than 175 people in the audience on April 27 — who had heard her read selections from her best-selling book, “The Other Black Girl” — wanted to know: How long did the book take to write? Did she feel exposed to the world, as much of the book is based upon her personal experiences in the New York publishing arena? What books would she recommend?

One audience member said she recognized herself, after a recent promotion at the U, as “The Other Black Girl” in her new office, which provoked rueful laughter from the people gathered for this University of Minnesota Libraries event on April 27. This was the latest in the NOMMO series amplifying Black authors and one of the first in-person events held by the Libraries in a couple of years. (Amiri Baraka, Angela Davis, and Roxane Gay are among the past speakers at NOMMO gatherings.)

Former head of the U of M Alumni Association Archie Givens, Jr., who is with his family a prime mover behind NOMMO, also was honored. The main attraction, however, was the vivacious Harris.

The author spoke at length with Lissa Jones-Lofgren, host of the Black Market Reads podcast, and then talked with people in the audience. Excerpts from the conversations follow.

Eavesdropping on conversations

Much of Zakiya Harris’s personal life is reflected in “The Other Black Girl.” Yes, she worked in a mainly white publishing house in New York City. She also grew up in what was then a small town in Connecticut.

“My dad wanted us to go to the best school in our town,” she told Jones-Lofgren. “It happened to be the whitest school. … My Dad, who integrated an elementary school in the 1960s, was very much like ‘Education, public education: This is the way.’”

Because the school was majority white, her friends in school were white, she says. In her teen years, she even wanted to “relax” her hair, a la Beyoncé. As a youngster, she was assigned the role of Phillis Wheatley, the first Black poet published in America — and also an enslaved person. Other Black kids in her class also were assigned Black roles in that school history play.

The audience listened intently to the reading by author Zakiya Dalila Harris at the Coffman Memorial Union Great Hall.

She began to take a second look at these childhood experiences only after she was enrolled in her Masters of Fine Art program in nonfiction writing at The New School in New York City.

“I had my own racial awakening in my early 20s, when I was living in New York, being around all these Black people,” she told Jones-Lofgren. “All these voices, and then the people I was reading.” She dived into pieces by James Baldwin, different from those assigned in high school, and works by authors such as Gordon Parks, who wrote “A Choice of Weapons.”

“My mind was blown open,” Harris said.

She moved from writing essays about her experiences to writing a novel in January 2019 — and completed it in October 2019. Even now, her Dad will sometimes call her Nella, the name of the protagonist in the novel.

“Do you feel vulnerable?” asked Jones-Lofgren.

“Totally,” Harris said. “People think I’m an Oreo: [that] I’m not Black enough. It is something that I am always aware of.”

Yet, as she has been talking with other Black and brown people who have been working in and moving within spaces dominated by white people and white-dominant culture, she finds they also “often feel like they have a double consciousness, like they have to police themselves.”

Beacons for Harris

A first-year undergraduate student asked Harris: “When did you see that fight and having to tone down our Blackness to succeed in this overwhelmingly white [dominated] country?”

“I had been really thinking about all the different ways that Black writers write about being Black, and talking with my parents about their experiences,” Harris said, noting that her dad’s dad founded the NAACP chapter in his town of Waukegan, Illinois, while her Mom’s dad didn’t have that same outwardly activist streak.

Her grandfathers were very different, with different upbringings, but both have been “kind of beacons for me,” Harris says. “Knowing that there is no right answer. Everyone has a different approach to how they are helping the cause.”

Another student, whose friends have lent him “The Other Black Girl,” said: “This is currently like the first PoC book that I’ll be reading.”

He asked: “You got any more book recommendations?”

“Whew!” Harris smiled hugely at the thought of naming just a few. “One book that I always say goes very well with this book — a wine pairing, if you will — is ‘Black Buck’ by Mateo Askaripour. After my book deal was announced, he reached out and said, ‘Our books are book siblings,’ … and they actually are.”

She also mentioned “The Final Revival of Opal & Nev” by Dawnie Walton, a novel about a fictional Black American musician and a white British musician who are a duo, for a time, in the latter part of the 20th century. “It’s a really fun representation,” she said, “in a way that is different.”

Although she clearly could offer more titles, lastly she mentioned “The Spook Who Sat by the Door” by Sam Greenlee. “I’m still processing this book; it’s so good,” she said. “It’s very subversive, a satire but not really, and also discusses tokenism and the ways that Black people have been used as pawns.” She didn’t want to give away too much to the audience; she did say she is looking forward to finally watching the 1973 movie adapted from “Spook.”

And we in the audience are looking forward to hearing more from her, as she tours with the paperback version of “The Other Black Girl,” releases a new short story — in the horror genre — and continues to develop her craft and refine her voice.

thank you Zakiya Harris, Archie Givens, Jr., Lissa Jones-Lofgren, and all the other splendorous spirits whose luminosity made this the cacAophony that smelled so soulfulfilling. perhaps this is an event signaling many brighter new beginnings.

xo