By Anne Good, Assistant Curator

We often find names written in the books that make up the Bell collection – inside the front or back covers, on blank leaves at the back of books, and even written across title pages. Most of these names mean nothing to me. When I’m not in a hurry or focused on a particular project, I occasionally pause and think about the person who might have read the book hundreds of years ago and felt strongly enough about it that they wanted to mark it as their own and add their name to the book’s history. I wonder how these books shaped their ideas about the world in which they lived. Below are a range of examples:

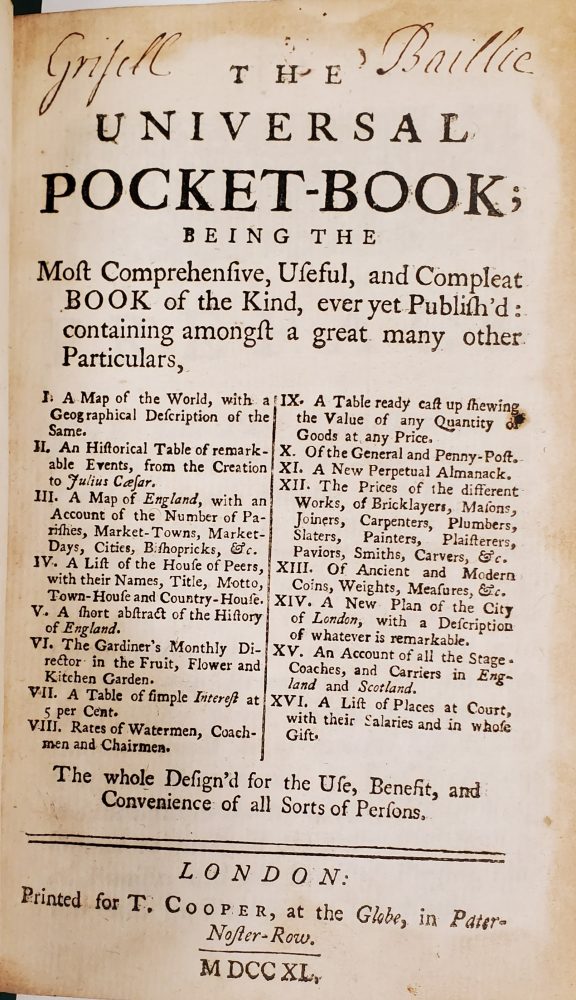

I had a moment of serendipitous coincidence not long ago, when I picked a book off the shelf in the vault: The UNIVERSAL Pocket-Book; being the Most Comprehensive, Useful, and Compleat BOOK of the Kind, ever yet Publish’d (LONDON: Printed for T. Cooper, at the Globe, in Paternoster-Row, MDCCXL [1740]). At the top of this title page, in a tidy, narrow script was written the name Grisell Baillie.

Just a day earlier, I would have flipped past the name, possibly without even reading it, to look for the map of London that was my target. However, one of my current projects is creating a “featured collection” to surface women in the Bell’s collection (more on that in the coming months), and the day before seeing Grisell Baillie’s name, I had been combing Jane Robinson’s Wayward Women: A Guide to Women Travellers (OUP, 1990). Grisell Baillie (1665-1746) is the first entry in chapter 5, “In search of the picturesque.” She kept a very detailed household book for a little over 50 years — a treasure-trove for historians of domestic life and much more. Robinson included Lady Grisell as a woman traveler because the household book “chronicles an epic family visit to the Continent between 1731 and 1733” (107).

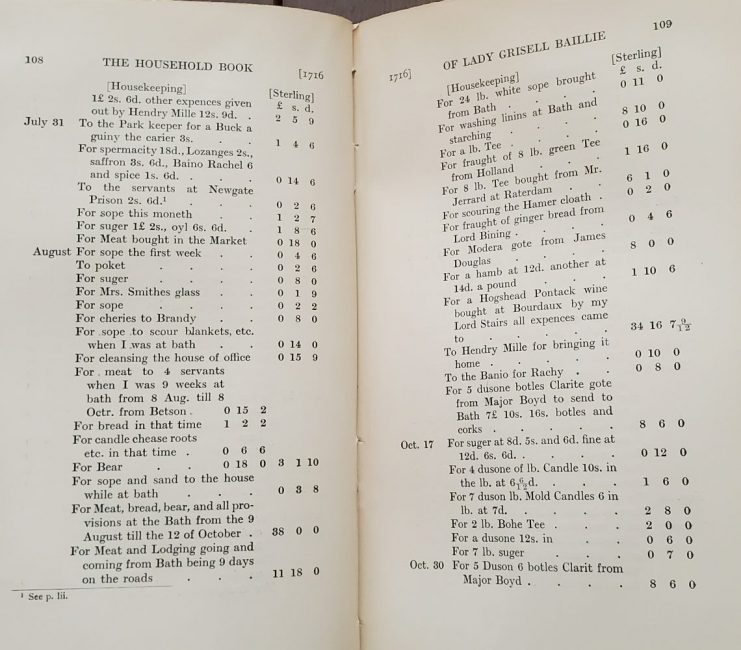

The Bell does not have the household book, unfortunately, but Wilson Library has the portion of the book that was printed in a scholarly edition in 1911: The Household Book of Lady Grisell Baillie, 1692-1733, edited by Robert Scott-Moncrieff, for the Scottish History Society, as Lady Grisell was a Scottish noblewoman. It contains sentences like this:

“So many sketches of Lady Grisell’s life have been published, dealing with her romantic history, her poetic talents, and her charming personality that nothing further need be said upon these points’ (xxx) [my italics]. Really? Perhaps this was so in 1911, but Lady Grisell is overdue for scholarly attention now.

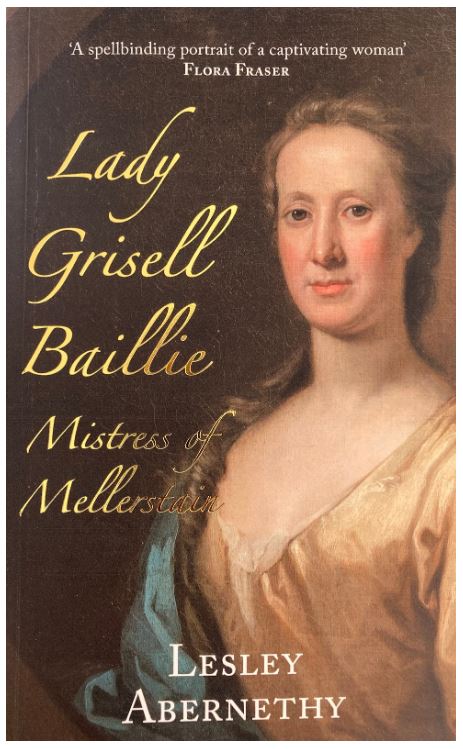

A beginning in this direction is a book published in 2020 by Lesley Abernethy, a guide at Mellerstain, the estate of the Baillie family. Lady Grisell’s future father-in-law, Robert Baillie, was implicated in a plot to assassinate Charles II, and horribly executed for treason. Grisell’s own family, the Humes, fled to the Netherlands, but returned to Scotland at the time of the Glorious Revolution. They became major political players, as did Grisell’s husband, George Baillie. They lived wonderful, comfortable lives, reflected fascinatingly in the household books.

Lady Grisell’s future father-in-law, Robert Baillie, was implicated in a plot to assassinate Charles II, and horribly executed for treason. Grisell’s own family, the Humes, fled to the Netherlands, but returned to Scotland at the time of the Glorious Revolution. They became major political players, as did Grisell’s husband, George Baillie. They lived wonderful, comfortable lives, reflected fascinatingly in the household books.

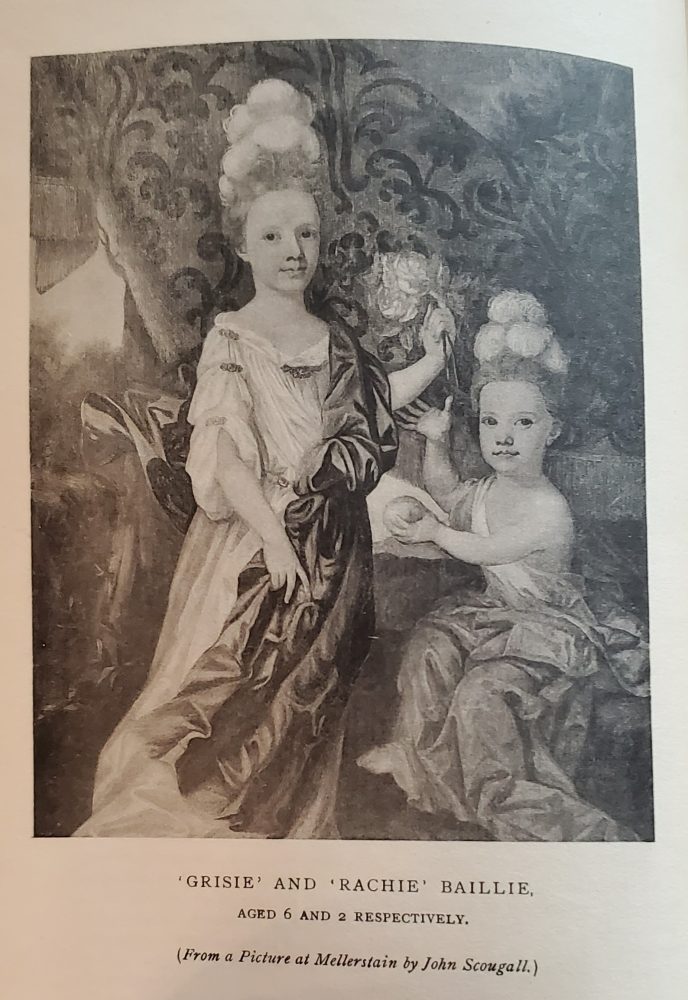

Grisell and George had two daughters: Grisell and Rachel. This inherited name, Grisell, makes it a bit difficult for someone not familiar with the family to follow which lady is doing what! The younger Grisell married unhappily; so much so, that her husband (Alexander Murray of Stanhope) was exiled from his family to protect his wife. Rachel, on the other hand, made an advantageous match and had a large and lively family. The younger Grisell, however, wrote a memoire of her mother’s life and was the one who preserved the account books. She was a friend of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, an intrepid traveler, and witty writer. Because of these connections, I would like to think that The Universal Pocket-Book passed through this Grisell’s hands on its way into the Bell Collection.

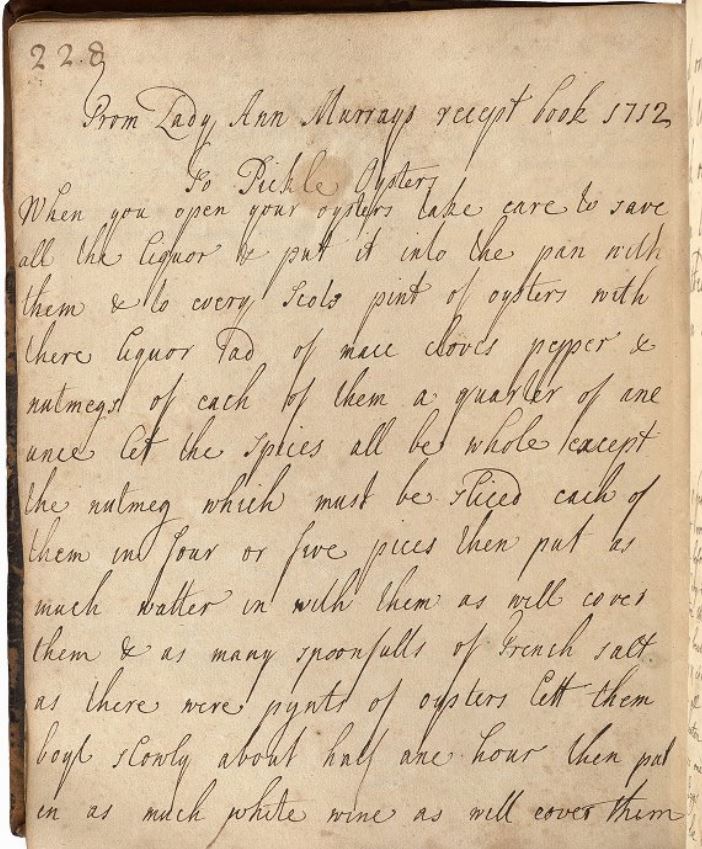

While looking around on the internet to see what else I might be able to find out about Lady Grisell, I discovered that a recipe book, The Accomplish’d Ladies Delight (1686), with her name written in it was sold by Sotheby’s recently for an amazing 10,000 British Pounds, though it’s originally estimated value was just £600 to £900! The success of this particular book at auction may be because a recipe book kept by Grisell Baillie and including recipes by numerous friends and acquaintances is also extant. The “Scots Cookbook Partly in the Hand of Lady Grisell Baillie” (W. a 111) is in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., and excellent work has been done by Lesley Abernethy (follow this link for another blog post about Lady Grisell) to identify the various contributors.

A page from the Baillie recipe book at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Abernethy has identified the handwriting as belonging to the younger Grisell, Lady Murray. This would have been her mother-in-law’s recipe for pickled oysters.

From the entries in the Household book, we know that the Baillie family members were avid readers and purchased books also while they were travelling in Europe. I think that these book collections were kept in two great houses, Mellerstain and Tyninghame. My sense is that, due to financial difficulties in the 1970s and 1980s, the Earls of Haddington, who had inherited the Baillie name and estates, began selling books, and finally had to sell Tyninghame completely. The Bell’s Universal Pocket-Book came from a London rare bookseller in 1980, but I haven’t yet turned up more Baillie books in the Bell’s collection.

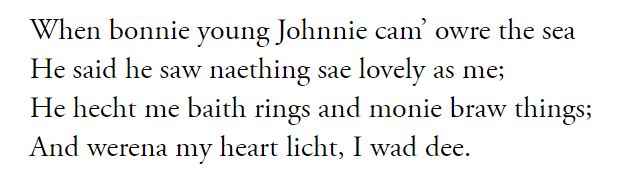

One last tidbit about Grisell Baillie is that she wrote songs in Scots, and her namesake daughter was “accustomed to sing the native airs and ballads of her own country with a delicacy and pathos quite peculiar to herself” (Scott-Moncrieff, xxviii). The manuscript of these songs was kept by the younger Grisell as well, but is now lost. A few of the songs were published in the 18th Century.

It is indeed rare to be able to learn so much about one of the people who scrawled a name in a book centuries ago, but this excursion into the life of Grisell Baillie makes me want to follow the signatures more often.