By Allison Campbell-Jensen

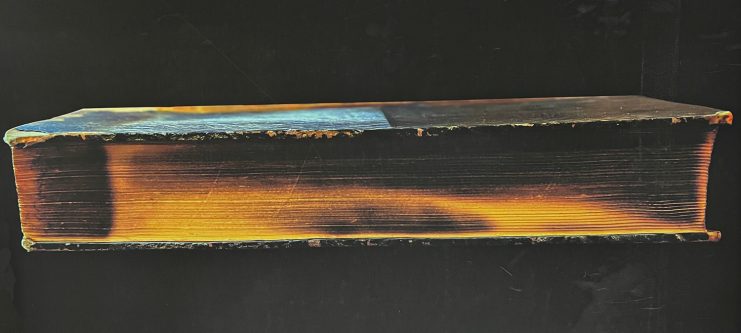

This scorched book, from the collection of gay physician and sexologist Magnus Hirschfield, was burned by Nazis. Photo credit: Laura Migliorino.

Renowned for its breadth and depth of works by children’s book authors and illustrators, The Kerlan Collection of Children’s Literature mirrors the issues of its times. So when Kerlan curator Lisa Von Drasek was asked, “Does the Kerlan have any banned books?” she responded: “Of course we do!”

Von Drasek adds: “The number one category of banned books is LGBTQ and sex education books.”

She cites the findings of PEN America’s groundbreaking report, “Banned in the USA”: Rising School Book Bans Threaten Free Expression and Students’ First Amendment Rights, first released in April, finding roughly 1,000 more book bans than previously reported.

Among the report’s key findings:

- Some 2,532 instances of individual books being banned, affecting 1,648 unique book titles

- A total of 674 banned titles (41%) involve LGBTQ themes or have protagonists or prominent secondary characters who are LGBTQ

- 659 banned titles (40%) feature protagonists or prominent secondary characters of color, with 338 banned titles (21%) directly addressing issues of race and racism

- At least 40% percent of reported bans listed are connected to “political pressure or legislation” designed to restrict teaching and learning

- Texas ranked first among states with the most bans (801 in 22 districts), followed by Florida (566 in 21 districts), and Pennsylvania (457 in 11 districts)

List of challenged/banned LGBTQ books

View a selection of books that have faced challenges or bans because of their LGBTQ themes and content.

In acknowledging Banned Books Week (Sept. 18–24, 2022), Von Drasek also looked back to her former work in a school library.

There was not a school term, she says, without a challenge to one of their books on the shelf. In challenging books, Von Drasek says, a parent might ask: “Why do you have “Captain Underpants” in a school library? The language is unacceptable.” A banned book, however, is a title that a principal or a school board says the librarian or teacher must remove from their shelves.

While parents may have agency and standing to prevent their child from reading a certain book, she notes, the threat to freedom comes from attempts to prevent any children from reading a certain book. Governors of some states and school boards in some states are, she says, “declaring what teachers can and cannot teach. They cannot say ‘gay,’” for instance.

Recoiling from censorship

A high school English teacher in Norman, Oklahoma, resigned “after posting a QR code directing students to the Brooklyn library’s Books UnBanned program, created to reach readers in places where books might be taken off the shelves.” (How the Brooklyn library helped fight book bans in Oklahoma, New York Times, Sept. 12, 2022.)

In response to a state law restricting what public schools could teach about race and gender, Summer Boismier covered books in her classroom with red paper because they were those “the state doesn’t want you to read.”

After she shared the QR code to access such books from the Brooklyn Public Library, a parent complained. The teacher was called to a meeting, and then resigned.

Von Drasek cited the incident as evidence of the chilling effect of challenging and banning books for young people. She says it resonates with her understanding of the history of Nazi Germany, and the recent release of the first installment of Ken Burns’s series “America and the Holocaust.”

“The first thing Hitler and the Nazis did was change the curriculum in the schools,” Von Drasek says. “Then they banned the books, banned people and authors, … and they lit bonfires of books.”

One of the surviving tomes from a book burning in Nazi Germany is held in the University Libraries’ Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies. The scorched book, from the collection of gay physician and sexologist Magnus Hirschfield, is a treasure of the Tretter, according to then-curator Lisa Vecoli, who appeared in a Secrets of the Archives video in 2015.

“Natural disaster, apathy, ignorance — [all those] can really cost us history,” Vecoli told interviewer Timothy Johnson. “But for the GLBT community, we are also aware that there are people who would like to actively destroy or erase our history and contributions of gays, lesbians, bisexual, and transexual people. For us, it’s symbolic of the need to have a dedicated archive that really preserves that information and makes it accessible for people.”

Banning books are among the first steps, Von Drasek says, “down the slippery slope toward fascism.”

Access is key

Intellectual freedom to access a variety of ideas and information is perhaps uniquely American, Von Drasek says.

“Under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, each of us has the right to read, view, listen to, and disseminate constitutionally protected ideas — even if others find those ideas offensive.”

Book challenges are bipartisan, she adds. When an exhibit that she helped to organize had elements such as “The Cat In the Hat,” “Caddie Woodlawn,” and “The Story of Little Black Sambo” challenged, she says, “we declined to remove them but did add contextual signage and recommended readings in response to the requests.”

Librarians must continue to confront those who would censor books.

“Their rights to voice opinions and try to persuade others to adopt those opinions is protected only if the rights of persons to express ideas with which they disagree are also protected,” Von Drasek says. “What censors don’t consider is that, if they succeed in suppressing ideas they don’t like today, others may use that precedent to suppress the ideas they do like tomorrow.”

There is no endorsement implied by a library having a book on its shelves, she adds. The library simply is doing its best work to represent as many points of view as possible.

Says Von Drasek: “If the library ‘endorses’ anything, it is your right to have access to a broad selection of materials.”

WOW! Powerful words here. Thank you, Lisa, for presenting this so well.

Norma Bondeson Gaffron