By Allison Campbell-Jensen

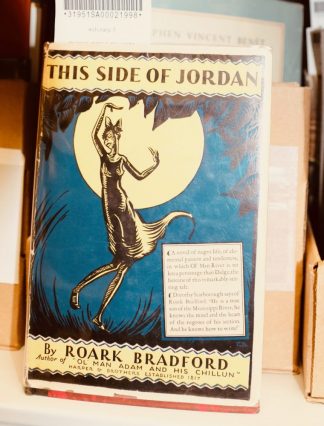

From W. E. B. DuBois to Amiri Baraka, from Countee Cullen to Angela Davis, from Zora Neale Hurston to Eartha Kitt, from August Wilson to Paul Laurence Dunbar, from the oral histories of formerly enslaved people to the poetry of Maya Angelou, from collections of spirituals to recordings of Twin Cities hip-hop artists, from the autobiography of Frederick Douglass to theatrical productions performed at St. Paul’s Penumbra Theatre, from works by photojournalist and film director Gordon Parks to the first African American author of a published book, Phillis Wheatley — the range of literary works contained in the Archie Givens Sr. Collection of African American Literature is as broad and deep as the Mississippi River.

And this list represents only a small part of the collection, which has nearly tripled from some 3,200 books, manuscripts, and other materials when it first arrived at the U of M Libraries to about 8,000 items. There are strong holdings of works by artists of the Harlem Renaissance, the papers of Penumbra founder Lou Bellamy, and other archives and incorporated collections encompassed by the Givens Collection umbrella. Still, the Givens, as some of its familiars term it, is not easily categorized.

Power of first-person voices

What unites it is the grit and truth and aspirations of Octavia Butler, Richard Wright, and many other writers, portrayals by and of the people too long held down, put down, and struck down by the dominant white culture in the United States.

While a BBC poll of writers brought “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in as the number two book of all time (after Homer’s “Odyssey”), it must be pointed out that those surveyed explained it was for the effect the book had on society. The witness of that white woman author of slavery’s viciousness made an impact — but not with the searing power of fear and pride, love of music and poetry, and the terror of separating families, that these first-person voices can — when they are heard, read, and passed along.

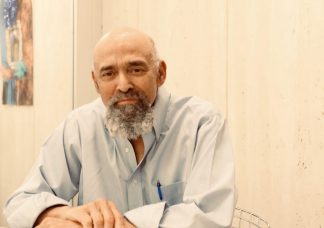

These voices can be very powerful, whether taken straight from the source or filtered through the mind of a poet. “I’m a scholar and a writer at heart,” says Professor John Wright, now Professor Emeritus of English and African American Studies. It was he who organized the initial University-community partnership to bring this collection to Minnesota in 1985. He has also ably filled the roles of curator, curriculum director, essayist, advocate, and exhibition organizer for the Givens Collection. Now that he is retired (officially, anyway), he would like to set the collection on a path to meet as many people as possible.

With the search on for a new curator, support from the Givens Foundation and the Minneapolis Foundation, and a renewed interest in the African American experience, the Givens Collection is poised for a refreshed start. Kris Kiesling, Director of Archives and Special Collections, sees an expansion of community outreach in its future, including to high school-age youth, to help engage them with African American literature, with the new curator also developing the collection and engaging donors.

“We want to lead a renaissance, if you will,” says Roxanne Givens, daughter of the late Archie Givens Sr., “so that individuals in the community once again feel the strengths and history of what the collection offers.”

Tribute to the Givens family

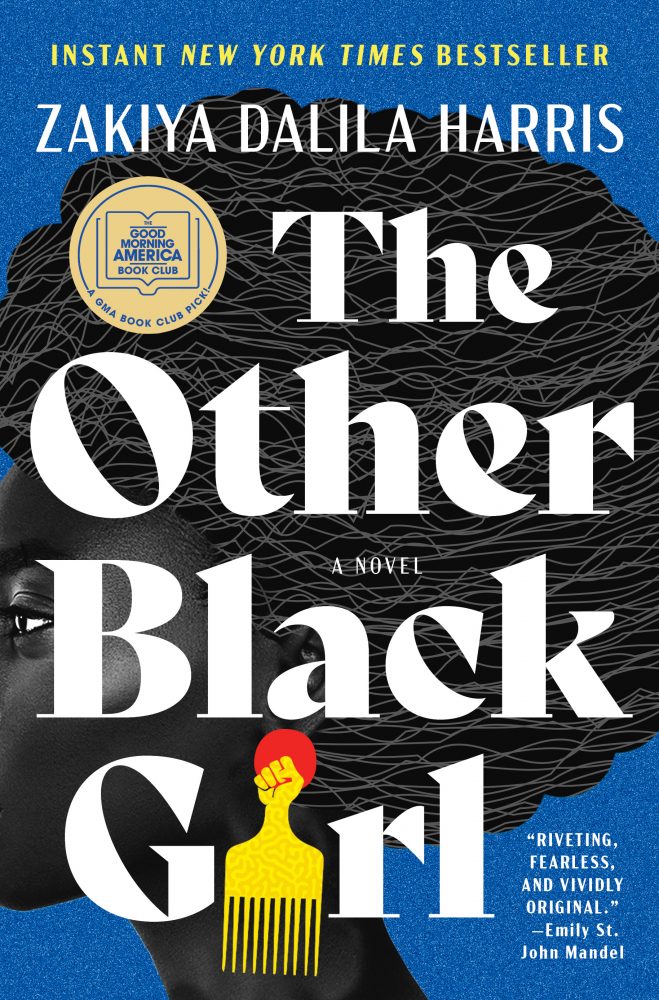

Her shower of tears surprised author Zakiya Dalila Harris as much as anyone in the audience on April 27. She had been invited by the U of M Libraries and the Minneapolis Foundation to read from her boffo debut novel, “The Other Black Girl” in Coffman Union’s Great Hall. And before the public program, she and nearly 50 other people had enjoyed a celebratory dinner honoring Archie Givens Jr., chair of the board of the Givens Foundation, longtime friend of the Libraries, and strong supporter of the University of Minnesota.

At the end of the dinner, actor and singer T. Mychael Rambo led the group in a just-created, crowd-sourced celebratory song that began: “Archie Givens is a majestic mountain . . ..” The honoree and his admirers made an impression on Harris — she was singing along with the dinner crowd of Givens’s friends and admirers. Then, when she arrived at the podium, her emotions spilled over.

In explanation, she told the audience she was moved by “the Givens family and how incredibly generous they have been and how much they have done for Black artists . . .. Part of what drives me is my family and the people who came before me.” The Connecticut native, on her first trip to Minnesota, paused: “I’m so excited to be here.”

And the crowd was excited to have her as the first artist to appear since the pandemic began in the NOMMO series featuring African American writers. The Givens family helped to found the series, just as they and others in the Black community had responded to the request from Wright to support the purchase of a collection of rarities in African American literature that became known as the Givens Collection, which continues to grow.

“We are proud of the Givens Collection and grateful to the Givens family,” says Lisa German, University Librarian and Dean of Libraries.

Discovered by chance

From center, clockwise: Archie Givens, Jr., Serena Wright, John S. Wright, Cecily Marcus, and photographer Tamar Patterson.

Serendipity played an important role in the discovery of the core of the Givens Collection. In the mid-1980s, Professor Wright helped Amy Russell, a student of his in the Afro-American Studies Department, land a job as an intern in Wilson Library’s Special Collections. One day, she happened upon a sale catalog detailing a collection of some 3,000 first editions and rare materials of African American literature and theater. She immediately alerted Wright, her advisor.

The materials had been gathered over three decades by a white New York City professor and playwright, Richard Lee Hoffman, who had been storing the collection in an expensive auxiliary apartment. After a second marriage, he needed to empty the apartment and find an alternative institutional home for his treasures.

“This was a chance for us to acquire, in one fell swoop, a collection of national stature,” Wright told a reporter shortly after the acquisition. To obtain it, however, meant raising money. Wright contacted the Dean of his College of Liberal Arts, Fred Lukermann, and together they approached then-University President Ken Keller about acquiring the collection. Keller gave them a loan (later forgiven) from his presidential discretionary fund for the needed funds.

To support the 1985 purchase of what was originally called the Black Studies Collection, Wright and collaborators Claudia Wallace-Gardner and Ezell Jones envisioned a “unique partnership” between the U of M and the Black community. They approached the family of Archie Givens, Sr., the first self-made Black millionaire in Minnesota. Says Roxanne Givens: “We were excited and thrilled to accept the challenge.”

Archie and Roxanne’s charismatic and visionary father had started his successful real estate career with an ice cream shop on the North Side of Minneapolis; and Roxanne’s mother, Phebe, was a college graduate. “Our family has always believed in education to inspire understanding and impart knowledge,” Roxanne Givens says. The Givens family proposed the idea of supporting this new collection to their friends.

As a result, a Patrons’ Council of 11 leading Black families was organized to join the Givens family in contributing the balance of the funds needed to repay the presidential loan. Raising $150,000 from the Black community in 1985 was not easy, she explains; collective philanthropy was a relatively new concept in the Twin Cities Black community, yet everybody rose to occcasion. The families who contributed to the purchase still take pride in their role in bringing this unusual and valuable collection to the University of Minnesota.

The original Givens Collection Patrons were:

- Steven and Sharon Sayles Belton

- Victoria Davis and Nathanial Khaliq*

- Fred and Earline Estes

- Richard and April Estes

- Phebe Mae Givens

- Roxanne Givens

- Fred and Toni Green

- Beckwith and Gwendolyn Horton

- Delbert and Marjorie Johnson

- William and Faye Johnson

- Ezell and Kim Jones

- Carol Meshbesher and Archie Givens, Jr.

- Cornell and Wenda Moore

- William and Alice Stubblefield

— with support from Claudia Wallace-Gardner and Dr. John S. Wright.

In the years since, some of these generous, notable people have passed away. Still, at the dinner honoring Archie Givens Jr., prior to the NOMMO reading and discussion by Harris, nine of the Givens Patrons were able to attend and to celebrate their legacy in the Givens Collection.

Legacy perhaps is not the correct word, however, because that word might lead one to think the Givens Collection is dead or stagnant. By no means: The Givens Collection of African American Literature continues to be, as it has from the beginning, a living, breathing, growing archive of outstanding African American artists, particularly in literature and theater.

Some of the constituent collections within the larger Givens Collection, like the Lou Bellamy Rare Book Collection, grew with the help of volunteer and one-time book dealer Bill Stevens. He goes through the collections, culls duplicates, sells them, and then puts the money in an acquisitions fund. His work is important and it is enjoyable for Stevens, a St. Paul resident. “It has been kind of fun for me in my retirement.”

Respect but not fame

The Givens Collection has been by no means a secret. Yet, even though the Givens family is well-known, the Givens Collection has not been as well known in the local community as it should be. R. T. Rybak, who may get a pass because he was busy being the mayor of Minneapolis for a dozen years, says that he, a friend of Archie Givens, Jr., never heard of the collection until about 10 years ago. But now, as head of the Minneapolis Foundation, he promotes the Givens Collection as one of the artistic assets of the Twin Cities.

After its purchase and initial processing in 1985, Wright and his collaborating team at the Weisman Museum were able to convey parts of the collection nationwide to people of all ages. They organized a renowned exhibition of Givens materials, “A Stronger Soul in a Finer Frame,” which was funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. As the first touring exhibition on the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ’30s, it not only toured throughout Minnesota but also to cities around the country. (See sidebar on the poem Baptism, from which the exhibit got its name.)

Outreach efforts also included creating curriculum guides for K-12 teachers and students, together with many years of well-attended summer teacher training programs at the University of Minnesota. When the public schools fell into money trouble, however, financial backing for teaching training disappeared and the University ceded this teacher training to other institutions of higher education.

In addition, despite the Twin Cities’ very rich book culture, there were no venues regularly bringing in Black writers. Wright and the Givens Foundation leaders then dreamed up the series of readings and workshops by Black writers called NOMMO, meaning in the West African Dogon language the “magical power of words.”

Starting in 2004, the NOMMO series was tremendously successful, hosting speakers from Angela Davis and Roxane Gay to Amiri Baraka and John Edgar Wideman, who gave presentations about history, drama, poetry, and public issues before large audiences. In 2015, however, the funding for NOMMO ran out, only to finally be restarted in 2022 with the help of the Minneapolis Foundation.

Throughout these forays into the public sphere, the Givens Collection has been located, like the other Archives and Special Collections at the University of Minnesota, literally underground. Stored in the climate-controlled caverns beneath the Elmer L. Andersen Library, the precious holdings — which include Jackie Robinson’s memoir; first editions of works by Claude McKay and Nikki Giovanni; and, according to Penumbra Theatre founder Lou Bellamy, three scripts by August Wilson that can be seen nowhere else — must be retrieved by staff in order to be examined by scholars or other visitors.

Yet once delivered to the Wallin Center Reading Room, they can be seen and even touched — no gloves needed. (Bring in only pencils, however.) When Rybak was offered the opportunity to pick up a copy of Wheatley’s poems, however, he said no. “I wanted to touch the book — but to me it was a pretty sacred text.”

Yet, along with Kiesling, those who have supported the collection from the start would like to see it used, brought to new audiences in new vehicles, and, yes, funded more generously so that it can be further expanded. Roxanne Givens, who serves on the board of the Givens Foundation, says the Givens Collection is “a cornucopia of just about everything pertaining to arts and literature. But because it is in the bowels of an institution, you have to know that it’s there to be able to access it.” Everyone should be aware of the Givens Collection, she adds.

Like Kiesling and Givens, Rybak would also like to see the Givens Collection spotlighted in the schools. “I am so pleased that we are now at a time when the messages that all kids get in school are much more representative of everyone in the community. However, I do not think we are yet bringing out the centuries of African American excellence [as illustrated in the Givens Collection] that would be deeply inspirational.”

St. Paul’s Penumbra Theatre

Lou Bellamy, the founder of Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul, whose records are kept in the Givens Collection.

Bellamy, who founded Penumbra, the African American theater in St. Paul that consistently punches above its weight, gave the theater’s archives and his personal papers to the Givens Collection. He did so, he says, “because of the size of the [Givens] collection and the context it gives to my work, which is largely done at Penumbra. That work doesn’t stand outside the theater and the culture.”

Penumbra Theatre hosted, promoted, staged, and gave breath and life to the cycle of plays about 20th century African American life created by one-time St. Paul resident, the late, great August Wilson. “You can follow it from the page to the stage,” Bellamy says of the archival value of Wilson’s works preserved in the Givens Collection, which include such hits as “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” “Two Trains Running,” and “Fences.”

While the playwright gave the producing, directing, and acting Penumbra company the words, Bellamy notes that it was the whole organization of people that made Wilson’s plays breathe with life. As in a well-remembered Penumbra production of “The Piano Lesson,” when a black man is ironing his uniform to work on the railroad, rhythmically singing as he creases his clothes into dapper style? Yes, Bellamy says, and adds with glee: “That was me! I played Doaker,” a lead character in the play.

Some observers claim that Wilson was a genius like no other; but when he talks with people about Wilson, Bellamy, who knew him very well, says that’s not the best way to represent the playwright. Rather, he was a regular person who gained insight through experience and research — and he worked very hard on his plays.

“It’s not a funnel from God that you’re special,” Bellamy says, gesturing up a cone descending into his head. He had to explain that to a young actor once when he directed Wilson’s “Gem of the Ocean” at the Guthrie; it wasn’t the caul the character was born in that somehow set Black Mary apart. “No, she’s a little Black girl who had this happen to her, as thousands did.”

He adds of ordinary people and artists: “That lets us all in. We all have potential.”

Myriad uses

His daughter Sarah Bellamy continues Penumbra Theatre’s work as a place of racial healing. She and Kiesling have been in talks about coming collaborations. “Once the new curator is in place, I’d really like to see that relationship blossom,” Kiesling says. “I think we have a lot to contribute, and I think having Penumbra tied more closely to the Givens Collection would be a great thing.”

The Givens Collection is for everyone: Every child, every person, especially anyone who has been shoved to the back of the bus or to the margins of society. With the lessons offered by the Givens Collection — there is nothing like a marked-up draft by a famous wordsmith to give a would-be writer hope — with the excellence that is held, protected, and also can be shared with community members at the U and beyond, one can sense that stronger soul being formed.

“In a community where George Floyd was murdered,” Rybak says, “and too many people said they were shocked by it . . ., we’ve needed our consciousness raised for a long time.” White people like himself, he adds, have been “clueless too long.” It’s time for white people to talk less, he says, and read more, to improve their understanding even if they cannot live the experiences.

The Givens Collection is part of an ecosystem, says Roxanne Givens, with the Givens Foundation, the U’s Department of African American & African Studies, the Penumbra Theatre, Umbra Search (hosted at the U of M website), Pillsbury House Theater, and Minneapolis Foundation. The wind’s blowing in a new direction after the killing of George Floyd, she says.

People have protested in the streets about the felt need to tear down the established order. Incorporating Black arts and literature and knowledge into the whole sphere of education will not change any aspect of racist killings and its implications — not immediately. But the Givens Collection offers a place to stand and push for advances in racial equity.

Over the years, the curator of the Givens Collection —most recently Cecily Marcus, who has moved into a position at the Minnesota Historical Society — “has been asked to shoulder an increasing burden of responsibility,” Wright says. Yet Kiesling is confident that a new curator with new ideas will open the door to new possibilities for the collection and its connections to the wider community.

And, its advocates say, the collection needs to be lit yet again. Says Roxanne Givens: “We have to work on all fronts to bring back its luster, to be the beacon it was intended to be.”

* His last name originally was Davis.

I remember Archie Givens as a running back at Central High School. He came into the periodical room where I paged books etc. I remember thinking that he was one fine person.