By Allison Campbell-Jensen

When is a portal more than a portal? When it combines strands of Mexican history and visual culture, American history, previously unacknowledged artists, and a decolonized approach to artworks.

Karen Mary Davalos, Professor of Chicano and Latino Studies at the U of M, and her colleagues who founded this more-than-a portal originally named it Rhizomes. Not far under the surface of the soil, rhizomes are plant root systems that reach far and connect many growing things in a nonlinear fashion.

“Migration Is Beautiful,” created by Favianna Rodriguez, who holds the copyright. Smithsonian American Art Museum; accessed via MAAS1848.

The work of Davalos and other scholars and collectors on this portal depends partly on collaborations with U of M Librarians Rafael Tarrago and Deborah Ultan. For instance, they have been instrumental in building the U of M Libraries’ collection through exhibition catalogs and art books that Davalos requests, thus developing the strengths of our U of M collections in these areas of Chicana/o art and scholarship.

“She [Karen Mary Davalos] is a great scholar,” says Tarrago, who is the subject librarian for Chicano Studies, History, Latin American Studies, Spanish and Portuguese Studies. He and Ultan, Arts & Design Librarian, also speak to Davalos’s classes and help graduate students access materials.

“Librarians are collegial,” Tarrago adds. Indeed, Davalos’s special research area also benefits from work opening up access by U of M metadata librarians, such as kalan Knudson Davis.

Says Davalos: “The U of M Libraries is this amazing resource that I didn’t know about — that they could do all these things for a scholar, for a professor teaching. I have been very grateful.”

Evolving: The portal formerly known as Rhizomes

“Six scholars, curators and archivists initiated Rhizomes in 2017, but the project quickly expanded to 25 people,” Alicia Eler reported in the Star Tribune Jan. 3, 2022. Rhizomes turned out to be a bit esoteric for those who are not gardeners or botanists. The team later chose a more straightforwardly descriptive name of Mexican American Art Since 1848 (MAAS1848).

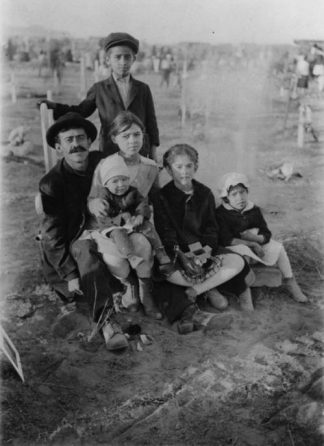

L to R Esteban Delgado, Chester (baby), Francis (holding baby), Steve (standing), Josephine and Alice Delgado. From the collection of the Los Angeles Public Library and found on MAAS1848.

Finding the artworks linked through Mexican American Art Since 1848 (MAAS1848) takes viewers to the originating institutions — libraries, archives, and museums, many of them focused on Mexican American, Hispanic, or Latinx artists. This is called a post-custodial or decolonized portal design by Davalos and her co-director, Constance Cortez of U Texas Rio Grande Valley.

What is a colonized work of art? How about “Winged Victory of Samothrace,” which now resides in the Louvre Museum in Paris, far from the Greek island where it once presided over a valley dedicated to the gods? It was excavated by non-Greeks in the 19th century, and brought West.

For the artists, collectors, and scholars who study contemporary Latinx, Chicana/o, and Mexican American art, knowing where and by whom the work is rooted and created is very important. “By receiving the visitor traffic through the portal, MAAS1848 credits the institutions which steward the art and related materials. This post-custodial design rejects colonial models of knowledge extraction and appropriation by operating an inclusive and democratic method for digital dissemination.”

The year 1848 is a turning point because in international relations, the United States of America is victorious in its conflict with Mexico. That war began because the federal government annexed what is now the state of Texas, a few years after it declared its independence from Mexico as the Republic of Texas. Thousands of people and hundreds of thousands of acres of land became subject to the U. S. government.

A growing field

While the expanding scholarly discipline of Chicana/o art is by no means unknown — Davalos herself has written three books about it, “Chicana/o remix: art and errata since the sixties,” and “Exhibiting mestizaje: Mexican (American) museums in the diaspora” as well as one about the Chicana artist Yolanda M. López — it has not been elevated to the top ranks in many museums and libraries.

Institutions currently linked to the MAAS1848 portal include the Smithsonian American Art Museum; Calisphere, The Portal to Texas History, the Digital Public Library of America, and a repository of documents digitized and made accessible by the International Center for Art of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. For the second iteration they plan to compile records from the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago and Mexic-Arte Museum in Austin, Texas. “Partnering with Hispanic-serving institutions, such as the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, and artists is essential to our work,” Davalos says.

Making the artworks and the artists known better goes beyond promotion; it also takes cataloging expertise. U of M Libraries’ staff has helped Davalos and this portal make an impact on the scholarly field.

Librarian Rafael Tarrago is one of the team of U of M Libraries staff who have been helpful to Davalos’s work.

Collaborating first with now-retired Librarian Stephen Hearn, as well as Jason Roy, Director of Cataloging, Metadata, and Digitization Services, and now kalan Knudson Davis, Rare and Special Collections Metadata Librarian, Davalos has been able to bring to light many people active in the Chicana/o-Latinx-Hispanic arts community.

Challenges for marginalized communities

One of Davalos’s scholarly colleagues, Arlene Dávila, the founding director of New York University’s Latinx Project, appreciates the professor’s work that overlaps with librarians’ tasks in metadata. “Thank you, Karen Mary Davalos for guest lecturing on how practices in digital archives make Latinx and artists of Ethnoracial backgrounds impossible to find and hence invisible,” Dávila tweeted in September 2022.

“Chicana/o art is a marginalized subject matter that it’s not yet part of mainstream institutions,” Davalos says. No one has been studying this field for a hundred years. So a part of the work is encouraging adoption of “new” artists’ names into authoritative lists (such as the Getty Research Institute’s union list of artists’ names).

“NYU students asked [Davalos] about the Getty’s ULAN [Union List of Names] response regarding the Rhizomes’ findings of invisibility&hellip. Scanning ULAN, it appears Getty accepted our proposed changes in 2020. We added 49 new artists, corrected 87 records, and provided 70 new authorized sources.” [See @rhizomes1848 and @arlenedavila1 on Twitter.]

Community matters

Cataloger Knudson Davis works with Davalos and her students to think through and then leap barriers. “One of our next steps is to work with community and add material to the portal that is not yet institutionalized,” Davalos says: items that are “not yet collected, or not collected at a library, archive, or a museum.”

For Knudson Davis, a part of the effort is taking into account terms that may not have been recognized previously, or “have been used in ways that are culturally inappropriate. . . . We [librarians] are holding ourselves accountable for past wrongs” such as using as subject terms “illegal aliens,” or other inaccurate or demeaning language. She adds that she keeps in mind the community the metadata is serving.

Knudson Davis notes that she has been asked by Davalos occasionally to not try to define certain terms. She respects the boundaries. Knudson Davis has heard that “the people who need to be defining these words are the community.”

Mexican American Art Since 1848 (MAAS1848) remains one component of the larger initiative, Rhizomes: Mexican American Art Since 1848. The Rhizomes Initiative has four parts:

- the portal,

- a book series,

- K-16 curriculum, and

- an institutional map to visualize and identify relevant collections across the nation.

In the first half of 2022, the MAAS1848 and Rhizomes project secured nearly $600,000 in combined support from three organizations: the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Humanities Collections and Reference Resources Implementation grant, the Mellon Foundation, and the American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Digital Justice Development grant.

This portal to aid the discovery of decolonized artworks and art history has established its roots and now can grow even more, with the help of librarians and diviners of metadata, to serve scholars and communities.

U of M resources for further research into marginalized communities

- Umbra Search features African American contributions to arts, humanities, and history. Currently, this U of M Libraries–hosted portal has 824,539 items from more than 1,000 U.S. archives, libraries, and museums. See also the U of M Libraries Research Guide.

- The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary (online), results from collaboration with the U of M American Indian Studies Department, the U of M Libraries, and the Minnesota Historical Society. See also the U of M’s Library Research Guide on Native peoples.

- See the U of M Library Resource Guide on Asian Americans. Also available from Bloomsbury / ABC-CLIO, The Asian American Experience provides a platform for academic research and scholarship on one of the fastest growing demographic groups in the United States. With scholarly essays, primary sources, and comprehensive reference articles, this unique digital resource brings depth and breadth of coverage to topics of critical interest to cultural and ethnic studies researchers.

- There exist Library Research Guides curated by U of M Librarians on a great variety of topics. Members of the U of M community also can access music from around the globe via Naxos Music Library.

We got in touch with Karen Mary Davalos because the period from Sept. 15 to Oct. 15 is designated National Hispanic Heritage Month, celebrating generations of Hispanic Americans through activities at the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Gallery of Art, the National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution, and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, among other institutions.

Yet, in conversation with Davalos and recognizing the opinions of her fellow scholar Arlene Dávila, we recognize that every month, every week, every day, should be an opportunity to celebrate the wonderful diversity that makes up American society: people whose heritage is Hispanic, Chicana/o, Latinx, as well as those who belong to Indigenous nations, Black people, people of South Asian heritage, Asian-Americans from many regions, and others who cherish or recognize an identity different from the dominant culture.

It’s a conundrum: To ignore the commemoration might appear insensitive while acknowledging BIPOC sources only once a year would appear shallow.

Attempts to expand coverage to all identities could be seen as analogous to health equity research, as explained by a Yale Medicine article during the depth of the COVID pandemic. “Community engagement, representation and inclusion in clinical trial data, plus asking different kinds of questions, are all key to advancing health equity research. … Yale experts discuss how health equity research has the power to ‘make the invisible visible,’ says Dr. [Marcella] Nunez-Smith,” leader of the Health Equity Task force for the Biden Administration.