By Anne Good, Assistant Curator of the James Ford Bell Library

Yearning hands, reaching out. Image captured by Natasha D’Schommer in Cornelis de Bruyn, Travels into Muscovy, Persia, and part of the East-Indies (London, 1737). Bell # 1737 fBr.

I recently read Feed, by M.T. Anderson, a novel in the future dystopia genre, aimed at a young adult audience, published in 2002. Like all the best dystopian fiction, this novel was visionary, and reading it today is at least a little painful. 2002 was a year before the launch of LinkedIn, two years before the start of Facebook, four years before Twitter, eight years before Instagram, nine years before Snapchat, 14 years before Tiktok – indeed, before any of the social media apps that now crowd our lives.

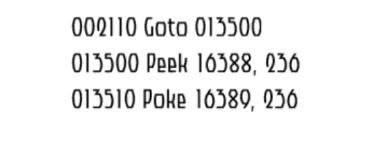

Anderson imagined a future in which people wouldn’t have to sit at computers or hold phones in their hands and use their fingers to type searches – instead, the “Feed” would be connected directly into their nervous system. They would be able to chat friends directly through visual stimuli, look up countless webpages connected to their brains, and algorithms would speak specifically to their consumer purchasing desires at all hours of the day and night.

One of the main characters, Violet, is the daughter of a professor of ancient computer languages and an environmental activist. Her parents didn’t want her to get a Feed, and when they finally gave in to societal norms (at age seven) they couldn’t afford the best version. They assumed that the second best, a cheaper version, would be fine, but when Violet suffers a hacker attack (at the start of the novel) it turns out that this was a big mistake. Because the Feed is fully integrated into the individual, when the Feed can’t be restored, the physical person also suffers.

“It’s the first thing my dad teaches the students on the first day,” she said. “It means, ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.'” Feed, 65-66.

Because she wasn’t integrated into the feed as a baby, Violet remains an outsider, able to think for herself and actively resist the Feed. Her ability to resist also means that, ultimately, none of the big tech companies have any incentive to fix her. As she goes into decline, she starts to make lists of things she wants to do while she is still able. I was struck by this one:

“7. I want to see art. Like, I want to remind myself about the Dutch. I want to remind myself that they wore clothes and armor. That some of them fell in love while they were sitting near maps or tapestries.”

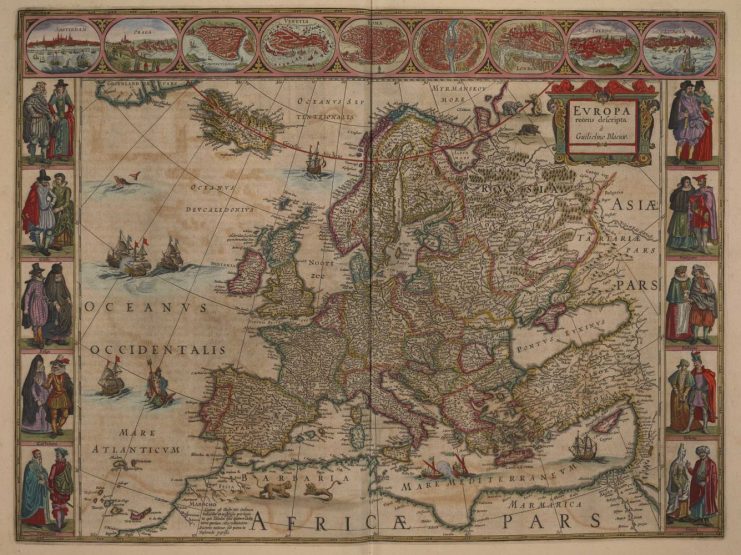

Where better to find maps and Dutch people than the James Ford Bell Library? I could readily imagine falling in love next to (and with!) Le Grand Atlas – the twelve-volume masterpiece of Dutch Golden Age cartography, with maps and commentary by Willem and Johannes (or Joan) Blaeu, first published in 1665. The Bell’s beautiful set was owned by a baroque-era pope, Clement XI. I imagine that the 12 volumes once resided in a beautiful gilt cabinet, like the one below from the University of Amsterdam special collections, before finding a home in the Bell’s modern vault.

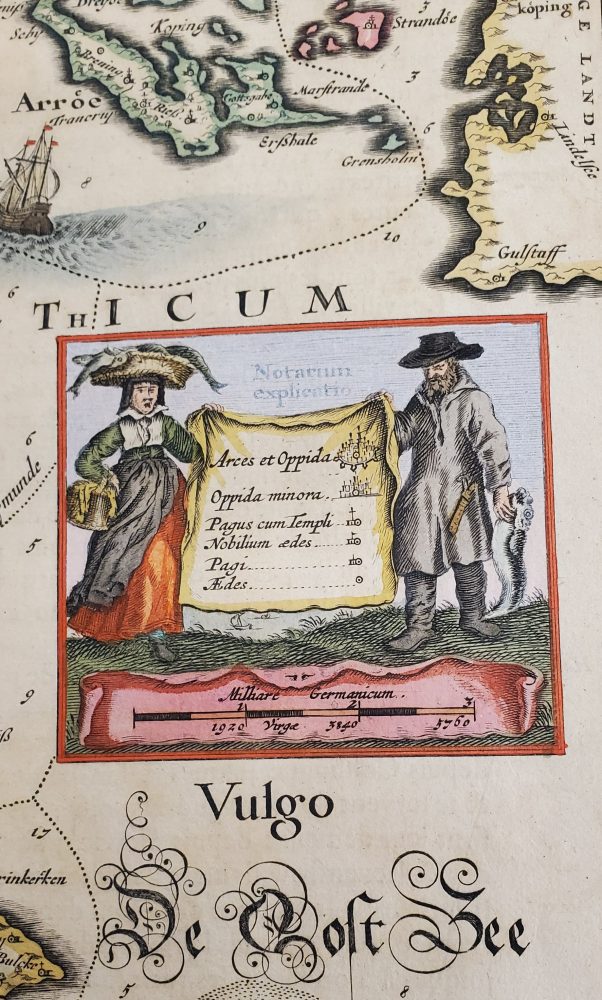

The geographical details of the maps were on the cutting-edge in their time period, and the artistry with which they were presented combine to make them enthralling objects.

Map of Europe, with embellishments, in Le Grand Atlas (Amsterdam, 1667). Bell # 1667 oBl. Explore the Blaeu map of Asia in UMedia.

There are many detailed, regional maps to love in all of the volumes, but my favorites are the largescale maps of the four regions of the world (Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas) surrounded by vignettes of cities and people in ethnographic dress. Usually these people are in couples – a man and a woman; occasionally pairs of men. Each set is intended to display typical and interesting attire from a particular area of the world.

The cartouche for the territory of Arnhem in the Netherlands. Bell # 1667 oBl v.4. See the full map in UMedia.

Vignettes in the cartouches of maps are also meant to engage and amuse the viewer. I was pleased to find Dutch people on several maps – and I imagine that the engravers intended them to be in love.

An exuberant working couple on a map of the region surrounding Groningen. Explore the full the map in UMedia.

Cartographic romance on a map of Brabant and Leuven. Explore the full map in UMedia.

Of course, it is always possible that Violet/M.T. Anderson was actually thinking of one of Vermeer’s famous works – but Vermeer loved Blaeu maps too!

“Officer and Laughing Girl” by Johannes Vermeer. More on Vermeer and maps here.