By Allison Campbell-Jensen

Perhaps you, you and your parents, you and your children, or you and your siblings have read “Millions of Cats,” out loud, to each other, or solo. This classic children’s book was first published in 1928 and, since then, never, ever has gone out of print.

Today, “Millions of Cats” may be purchased online as a paperback for $6.50 — or, if one prefers a rare first edition, for hundreds or thousands of dollars. (Not millions of dollars, however.)

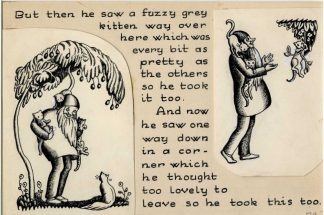

“Millions of Cats” by Wanda Gág process art: An old man under a tree looking at a cat and an old man holding several cats in his arms. (Hand Lettered, india ink illustration); Kerlan Collection of Children’s Literature.

In 1929, the “Cats” book, written and illustrated by Wanda Gág (and lettered by her younger brother), was one of six to be honored with a Newbery, a literary award given by the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC), a division of the American Library Association (ALA), to the authors of “the most distinguished contributions to American literature for children.”

And the story of the creator of “Millions of Cats” begins in Minnesota. Many works created by Wanda Gág are held in the Kerlan Collection of Children’s Literature, one of the special collections at the University of Minnesota Libraries.

Raised in an eccentric show home

In a New Ulm, Minnesota neighborhood that otherwise demonstrates solid German sense — being punctuated with brick houses built to last — the home that Anton Gag built stands out. Its seven original colors have been restored, its seven shapes of windows chosen by the artist father revealed — perhaps the only major thing missing are the voices of his seven children, calling from the second-floor turret to their friends to come and play.

With help from the Minnesota Historical Society, in 1988 the Wanda Gág House was stripped of unsightly siding and a late-added porch. The original colors were brought back to life and spires carved and replaced atop the roof. Inside, the home has been refurbished to be the showcase of intense hues, spritely figures, and trompe l’oiel flourishes that Anton displayed to show potential clients what he could do in their homes.

An immigrant from Bohemia, Anton Gag was a musician, a photographer, and a painter. In his second-floor photography studio, he opened up heavy curtains on the east-facing windows to bring in the morning light. He also had a compact male zimmer (painting room) — really more of a nook with a huge, slanted skylight. When the room became Wanda’s, she used to complain about the skylight leaking during rainstorms.

After he quit photography, father Anton moved his art studio up to the attic where, unless he was smoking a cigar, the children were always welcome. They had a toy carousel created by their uncle, with 4-inch wooden horses, and a couple of low-ceiling annexes in which to play and draw and sing.

The oldest and youngest of the seven children, Wanda Gág and Flavia Gag, became artists in their own right. Wanda was 15 when he died; Flavia, barely 1 year old. Wanda had been mentored by her father; Flavia, who also became a creator of literature for children and young adults, was mentored in turn by Wanda. Wanda ended up moving east, to New York City, and then the surrounding countryside. Flavia moved south, to Florida, where she died.

New Ulm remains proud of the Gág family, with a statue of Wanda depicted drawing a cat in front of the public library, and much of the painting by Anton Gág and his two painting partners salvaged in the restored interior of the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, a few blocks from their house.

More recently, the Wanda Gág House acquired a mirror from one of her homes out East. It is now paired with a self-portrait of herself, showing front and back sides, originally drawn in front of this exact mirror. The local trucking company, J.W. Schagel, carted the fragile artifact from Connecticut to New Ulm.

Meet the artist at the Kerlan

Wanda Gág’s papers, manuscripts, photographs, and pencil and India ink drawings; hand-written lettering by brother Howard; and, dummies for her children’s books are held in:

- The Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota Libraries

- The New York Public Library

- The Free Library of Philadelphia, and

- The Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia)

The U of M Libraries also holds books by and about Gág and, online, an audio show of appreciation featuring Karen Nelson Hoyle, then curator of the Kerlan, and scholar of popular culture Karal Ann Marling.

Gág’s prints, drawings, and watercolors are in the collections of Mia, The Whitney Museum, and other museums around the world.

Gág provides a charming self-introduction in “Growing Pains: Diaries and drawings for the years 1908-1917.” With accounts of her early works, admonishments to herself, descriptions of infatuations, and sketches of her family and friends, this self-portrait of the artist as a young woman discloses her commitment to Art and her difficulties with Love.

Toward the end of the book, Gág wrote:

“Love is certainly a complicated business. Perhaps I am not qualified to judge but it looks like one big eternal, undependable tangle to me.

“The other evening Adolphe declared it must be an awful risk to marry. I have often thought it, but it seems that a woman has more cause to be afraid of marrying than a man has. Adolphe is afraid that one might get tired of the other or fall in love with another, or something. There is that danger, of course, but surely that danger is lessened if one chooses one’s mate keeping in view character, broadmindedness, intellect, and aptitude for progress. …

“In a way it is really much more peaceful to have a couple of half-cavaliers and Platonic Friends (as long as they last) than to narrow oneself down to one man. When you narrow yourself to one man you are always so concerned about him, about his attitude towards you, and your attitude towards him, etc. — whereas when you have a string you enjoy them all more or less dispassionately and you aren’t nearly so sensitive to their words and actions.

“It may be due to my extreme youth that these things seem so important to me.” [p. 455]

Or it could be that her attitude reflects her awareness of the demands on married women of the 1920s: to raise children, do the household chores, and in other ways perform as a help-meet to their first-place-in-the-family mates? Because that is what she engaged in, as head of the family following her father’s death when she was 15. Her mother had fallen ill and was not able to help much around the home; she died about seven years later.

Wanda chose Art. Developing a distinctive style of seemingly animated, dancing, leaping line drawings, her signed work appeared in the Minne-Ha-Ha, a comic publication of the University of Minnesota’s student-run Minnesota Daily while she still was an art student in St. Paul.

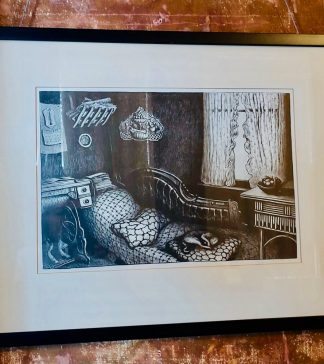

When, with the help of sponsors, she moved to New York City, she began to evoke the spirits embodied in the mundane. From a fire hose in a Macy’s department store stairwell, to elevated train stations, to kerosene lanterns and their shadows, and to trees whipped into frenzies — every subject appeared as it should, to the eye, yet also somehow charged with energy.

“[H]er prints are treasured for their commonplace subjects handled in an exuberant, jaunty, and unique style,” wrote Audur H. Winnan, in a catalogue raisonné. Yet there are depths in Gag’s work, Winona added, in the alterations of traditional approaches to making prints (she used sandpaper!) and insights offered by her writings, which “more fully illuminate the complexities of her personal style” based on delving into her sensuality, as well as her relationships with imposing figures in the New York art world of her time.

Drawn to succeed

Born in 1893, Wanda was the eldest of seven children of Bohemian artist Anton Gág and his wife, Elizabeth. He was an accomplished oil painter who decorated houses and churches in an Old World European style.

When her father was dying, too young, he charged her with finishing his artistic work. She took responsibility for her younger siblings.

Eking out a life insurance payment over several years, combined with $8 a month from Brown County, Wanda also created art works for local ladies’ dining table place cards, as well as illustrations and stories sent to a local newspaper. After graduating high school, she taught in nearby Springfield for one year, and — with help from relatives on nearby farms who brought vegetables or loads of wood — she scraped together enough to keep the other children warm and fed (mostly, most of the time).

Benefactors who recognized her talent helped her attend art school in St. Paul. With additional financial support, she then moved to New York City to study and create art.

“In 1925, a gallery owner saw her work, bought it en masse, put it on display, and sold it all,” wrote Alice Gregory in the New Yorker. “Gág used the windfall to rent a farmhouse in Connecticut, where she created a body of new work that was given a solo show and met with rave reviews.”

With the success of “Millions of Cats,” she received more offers to create children’s books, such as re-telling and illustrating Grimm’s fairy tales. While she did some, she chose to focus on other work: sketching, print-making, and experimenting with imagery, materials, and design.

“She could cause a fireplace to set andirons dancing,” Winnan writes. “She portrayed a giant of a stone crusher, a mechanical contrivance frightening the flowers. …

“The work of Wanda Gág is among the most intriguing bodies of graphic art in this [20th] century. Her poetic stylization and the abundance of energy flowing through her prints and drawings make them unique. They are timeless, fresh, and vital . …”

She also was published in such progressive magazines as The Nation, New Masses, and The Liberator during the 1930s and ’40s.

It is “Millions of Cats” that still enchants children and those who read to them, with illustrations pulling them over hill and dale following the simple tale of an old man seeking a cat for his lonely wife. Having the art and text together, and the story running over the gutter on two-page spreads, were innovative for children’s books.

If, by some chance, you have not yet read “Millions of Cats,” we must reveal to you that it has a happy ending … well, happy for some!

Her fable “Gone is Gone,” about a husband attempting to switch duties in the field with his wife’s seemingly easier tasks on the homestead — and failing spectacularly — also remains very popular, says Wanda Gág House tour guide Barb Saffert. Particularly at bridal showers.

Marriage

Wanda Gág married late. Beforehand, according to sources, she enjoyed several love affairs with men. In an autobiographical essay published in the 1920s, she wrote: “If papa had only known what a hotbed of feminists he was starting, he need not have worried so about having a boy; for, with one exception, all his daughters bid fair to remain [Gágs] through all the mutabilities of life and marriage.” [“These Modern Women,” p. 132]

Living in the country, in rustic places adjacent to New York City, appealed to Gág. Late in her life, she was able to buy a farm of her own in New Jersey. She died in 1946 of lung cancer. The few oil paintings she produced did not meet her standards and were never released for public viewing.

Her accomplishments remain. “A million copies of ‘Millions of Cats’ had been sold by Gág’s centenary year, 1993, 65 years after its publication, …” writes Karen Nelson Hoyle. “Translations to a dozen other languages make the book accessible to children around the world.”

Sources

Original artwork by Anton Gag and his team, with white background, in the restored Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, New Ulm; taken in 2023. The Minnesota Digital Library holds a photo of the original artwork.

- Barb Saffert, tour guide, Wanda Gág House, New Ulm, Minn.

- “Growing Pains: Diaries and Drawings for the Years 1908–1917,” by Wanda Gág; first published 1940; re-issued by the Minnesota Historical Society Press in 1984, with additional materials.

- “Millions of Cats,” by Wanda Gág, Coward-McCann, Inc., New York, 1928.

- The New Yorker, Juicy As a Pear: Wanda Gág’s Delectable Books, By Alice Gregory; April 24, 2014, accessed online Jan. 3, 2023

- “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” freely translated and illustrated by Wanda Gág; 1938, University of Minnesota Press; Series: Fesler-Lampert Minnesota Heritage Book

- “These Modern Women: Autobiographical essays from the Twenties,” edited by Elaine Showalter, The Feminist Press, 1978.

- University of Minnesota Archives, available on prior request in the Wallin Reading Room and also online: Minne-Ha-Ha (a publication of the Minnesota Daily), 1917 & 1918.

- “Wanda Gág,” by Karen Nelson Hoyle, Twayne Publishers, 1994.

- Wanda Gag, Minnesota Artist, audio recording with Karal Ann Marling, Professor, Department of Art History; University of Minnesota Radio and Television Broadcasting records (ua 01039). This University Archives project was supported by a Recordings at Risk grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR). The grant program is made possible by funding from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

- “Wanda Gág: A catalogue raisonné of the prints,” by Audur H. Winnan, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993.