By Allison Campbell-Jensen

Thacher Hurd’s introduction to Margaret Wise Brown was not especially promising. Brown, the renowned author of “Goodnight Moon,” which his father Clement Hurd had illustrated, had no children of her own.

Nonetheless, she wanted to make things very special when Clement Hurd and his wife Edith Thacher Hurd brought their 2-year-old son (John) Thacher Hurd to Brown’s remote Maine island retreat. The three were all collaborators and friends (Edith Hurd also worked with Brown on children’s books).

In line with her recently published book “Little Fur Family,” Brown had prepared a little fur room for Thacher:

“with fur pillows, fur blankets, and a leopard-skin rug … complete with the head preserved, teeth displayed, and glass eyes glaring. … At the sight of the rug, he screamed in terror.”

— “Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon,” by Leonard S. Marcus, p. 260.

Connection to the Kerlan

The Hurd family’s connection to the Kerlan Collection of Children’s Literature at the University of Minnesota Libraries is long-standing. One day, in the old Vermont farmhouse that his parents loved, Clem called out to his son from the attic.

“Look what I found: Margaret’s original script dummy for ‘Goodnight Moon’!”

His father personally delivered it to the Kerlan, Thacher Hurd remembers: “That was his first impulse.”

Interestingly, Thacher adds, there were two more lines at the end of the original dummy: “Goodnight cucumber. Goodnight fly.” Fortunately, they were dropped, and words evoking shelter, food, and safety remained, such as “Goodnight mush….”

Along with pieces created by his father and mother, Thacher Hurd’s dummies for printers and works of children’s literature also are held in the Kerlan.

“It’s a great resource for children’s book authors,” says Thacher Hurd, who credits former curator Karen Nelson Hoyle and current curator Lisa Von Drasek for the great breadth of the collection.

Rock-n-roll or . . .?

These days, “Goodnight Moon” is 75 years old and counting — initially, its popularity grew slowly, yet it has never been out of print. As for his introduction to Brown, Thacher Hurd perhaps remembers the story more clearly than the actual event. Despite the scare, he regrets that he never really knew “Brownie,” as he calls her, for she died only one year later.

With this wild introduction, however, and his upbringing both East and West — his family moved to Northern California yet continued to summer in Vermont — Thacher Hurd eventually grew into a career of his own as a children’s book creator.

Many children do not readily follow their parents’ paths. As a teen, Thacher Hurd thought he might play baseball, or be in a rock-n-roll band. He did pursue art during his college years — he studied fine art at the College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland.

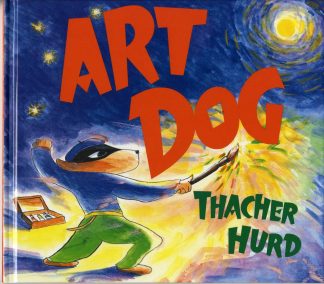

After graduating, Hurd found himself bored with painting, And he started working on books, first illustrating a book that his father gave him, and later working on a children’s story with his mother. With his own illustrated stories like “Art Dog,” “Mama Don’t Allow,” and “Zoom City,” by the 1990s, he became an esteemed children’s literature creator.

While Thacher Hurd was writing and illustrating books for children (he has now retired and paints in oils again), he would spend a good amount of time musing on ideas.

He would write down the better ideas, but if they didn’t “stick,” Hurd says, he discarded them. He adds that other ideas “come along like a freight train — they intrude on your life and want to be done.” So they were done, to acclaim.

Openness marks the Kerlan Collection

“A good children’s book is a communal thing.”

—Thacher Hurd

Leonard S. Marcus, who has written extensively about children’s literature, authors and illustrators in “Show Me a Story,” “Pictured Worlds,” “The ABC of It,” and many other books, admires the Kerlan Collection and praises the University of Minnesota, which provides public access to such collections, including the original art of “Goodnight Moon.”

“I’ve been to lots of archives and special collections. [In the past, the curators’ attitude often was] ‘We have all these rare things and, if you’re lucky, we’ll let you look at them.’ The Kerlan has always been the opposite of that.”

“Goodnight Moon” was ahead of its time, says Marcus, partly in the sense that librarians of the 1940s were not generally interested in interactive books that invited the child’s participation, and “were skeptical of the theories of early child development that had inspired that approach.”

In an earlier era, many public libraries didn’t serve children, Marcus notes. At the turn of the last century, the minimum age was often 12. Then New York Public Library set the practice of admitting 5- and 6-year-olds who “could sign their name to a guest book … and pledge to take care of the books.”

Of “Goodnight Moon,” he adds, “It seemed like such a strange book at the time. There was no hero — and no story. The little bunny just lies there!”

Goodnight well-wishers

Sometimes a bunny lying there is all a child needs. Thacher Hurd remembers his favorite story from the many contributed by New York Times readers after last year’s 75th anniversary appreciation of “Goodnight Moon.”

“There was a dad on a night flight with an infant who was screaming,” Thacher Hurd says. “He pulled out ‘Goodnight Moon,’ and started reading aloud to him.”

Then, as the Times recounts Liz Casey’s story: “Unexpectedly, a woman in the next row started reciting the words right along with the dad. Another joined her, then a few more, and pretty soon it seemed as if every one of us was paying homage to the comb and the brush and the bowl full of mush. It was a concert of parents wrapped in memories, sending love and good nights to the littlest one among us.”

Then the child fell asleep; the parents sighed. Goodnight plane.

“A good children’s book is a communal thing,” Thacher says.