Anne Good, Assistant Curator

I was intrigued by a story that recently appeared in the Smithsonian Magazine (online) about an archaeological find in southern Vietnam. The site at Óc Eo is nearly 2,000 years old, and analysis of several grinding stones found there revealed traces of “turmeric, ginger, fingerroot, sand ginger, galangal, clove, nutmeg and cinnamon.” These flavors are exciting of themselves, but their presence also reveals remarkable, early, trade and cultural networks.

Ground spices!

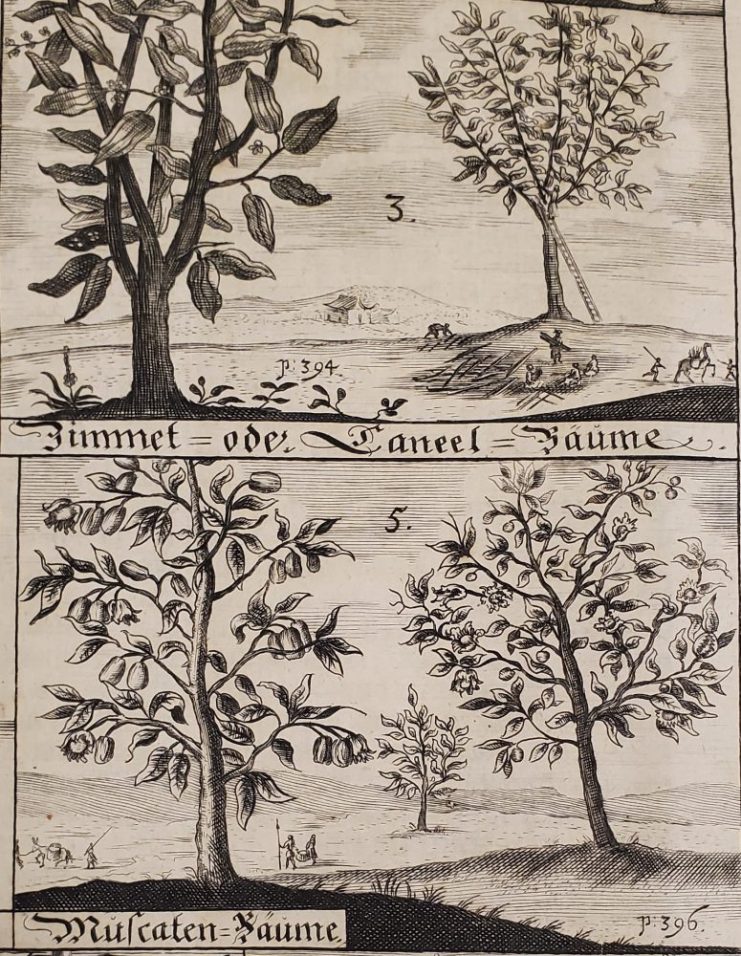

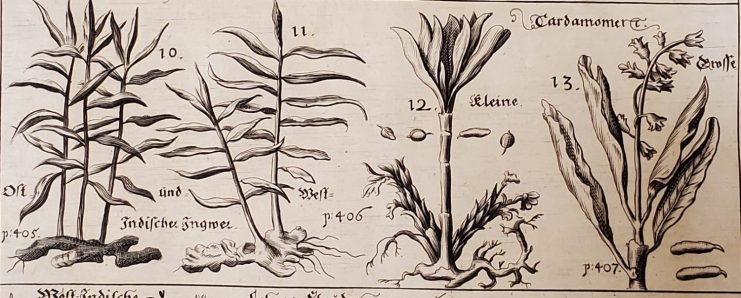

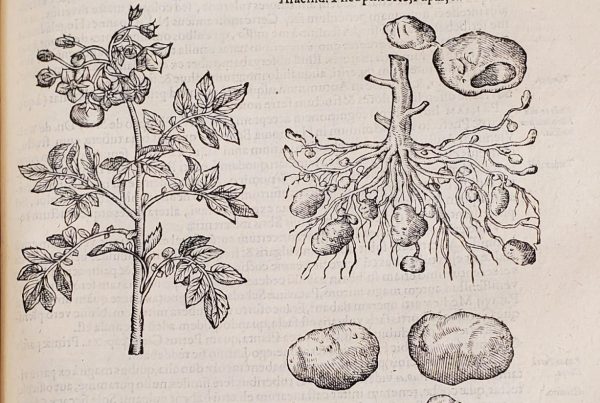

To tie this story to the Bell collection, first of all a gallery of early modern depictions of several of these spices from a book that is like a curiosity cabinet: Erasmi Francisci’s Ost- und west-indischer wie auch sinesischer lust- und stats-garten mit einem vorgesprȧch von mancherley lustigen discursen (Nuremberg, 1668) – 1,762 pages! [Erasmus Francisci’s East and West Indian, as well as Chinese, state and pleasure garden, with preliminary talks on various funny discourses; Bell Call # 1668 fFr.]

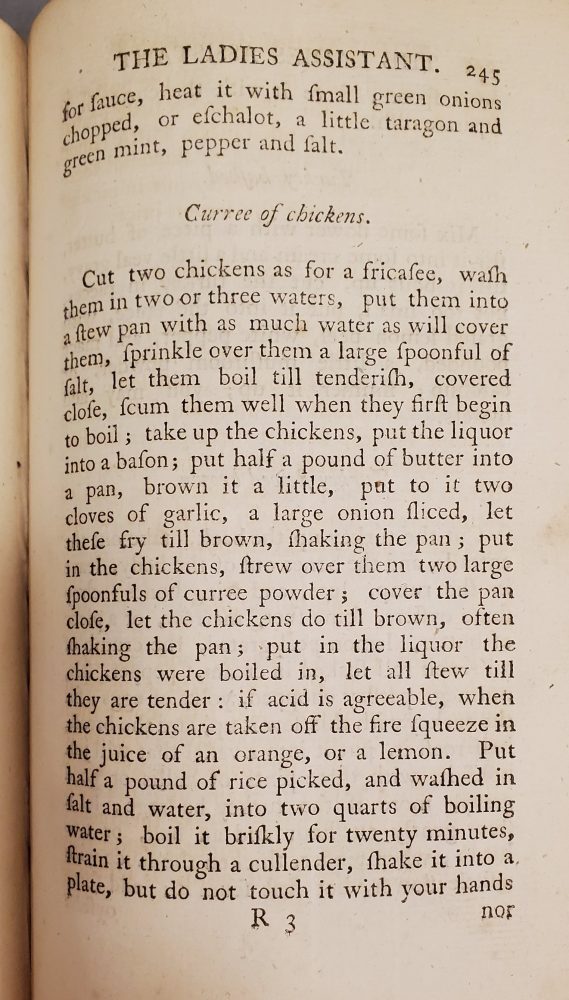

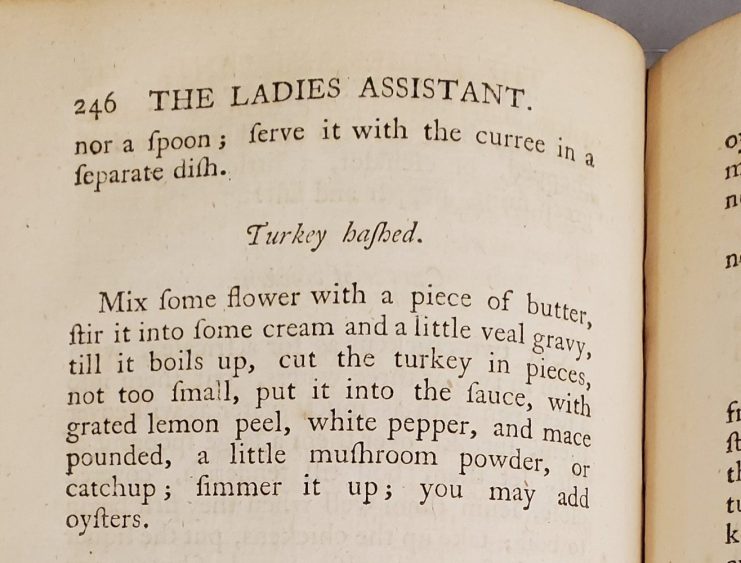

The Bell Library doesn’t have any 2,000-year old evidence of mixed spices, but we do have a recipe for “curree” from Charlotte Mason’s The lady’s assistant for regulating and supplying her table : containing one hundred and fifty select bills of fare, properly disposed for family dinners of five dishes, to two courses of eleven and fifteen, with upwards of fifty bills of fare for suppers from five dishes to nineteen, and several deserts including a considerable number of choice receipts of various kinds, with full directions for preparing them in the most aproved manner, now first published from the manuscript collection of a professed housekeeper, who had upwards of thirty years experience in families of the first fashion (London, 1773) (Bell Call # 1773 Mas).

Unfortunately, Charlotte Mason only refers to “curree powder.” She doesn’t tell us exactly which spices were in the mix, and in which ratios, so we don’t really know what this 18th-century version of this iconic dish would have tasted like. She probably bought the spice mixture at an apothecary or similar shop, where it would have been advertised for both its taste and its healthful benefits. [This link will take you to the British Library to see the earliest British advertisement for curry powder.] Interestingly, the ancient grinding stones did not include traces of pepper, but we know from letters and other descriptions, that by the 18th century, diners would have expected the “hot” flavor of added pepper corns and perhaps even chili peppers.

For a more in-depth look at the history of curry, I highly recommend Curry: A tale of cooks and conquerors by Lizzie Collingham.