By Adria Carpenter

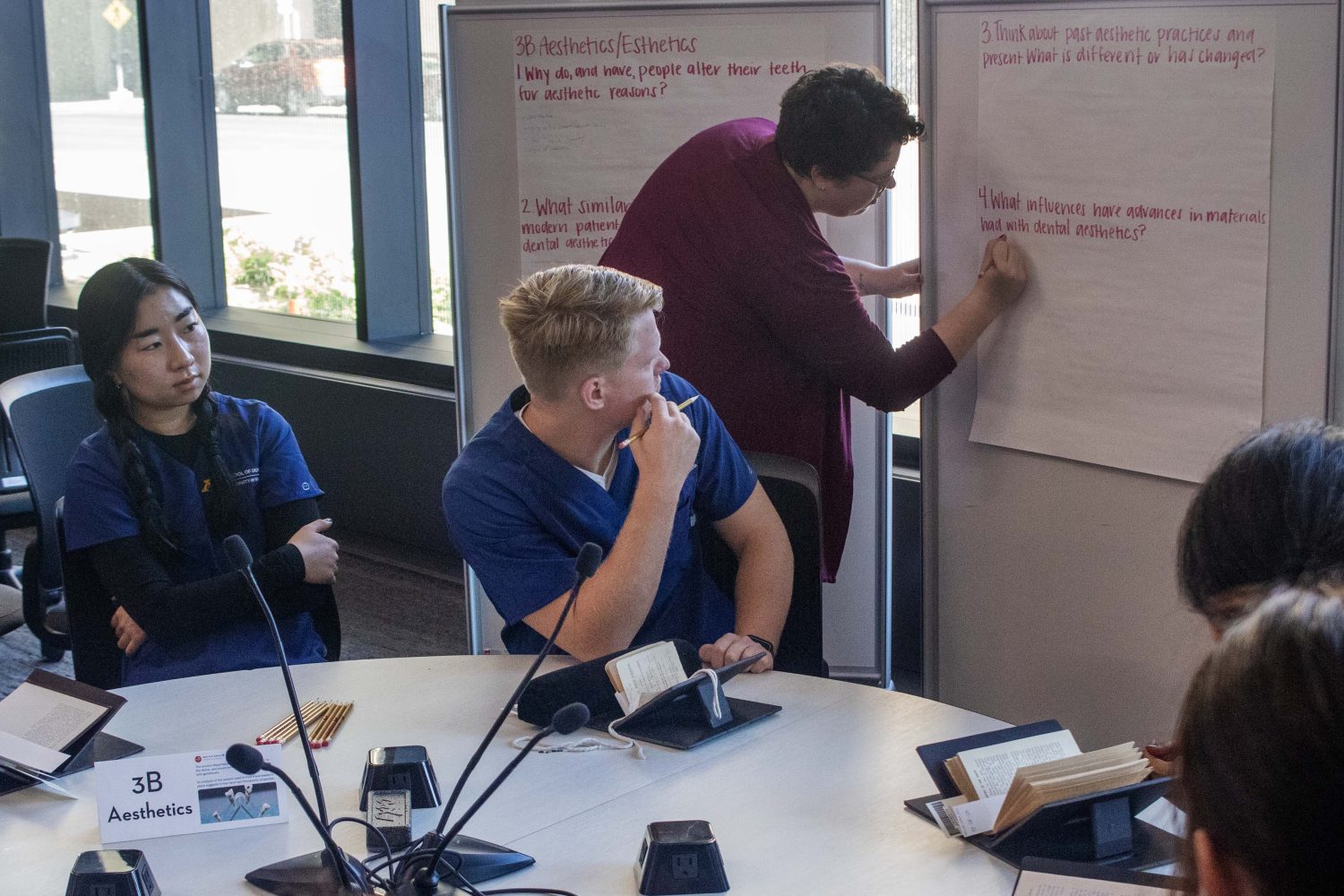

Tomorrow’s dentists, orthodontists, and practitioners are experiencing the profession’s history firsthand and reimagining its future, thanks to a partnership between the University of Minnesota Libraries and the School of Dentistry.

As part of their Dental Professional Development 1 course, all first-year dental students learn about the history of dentistry, usually taught in one class period in a linear, lecture format.

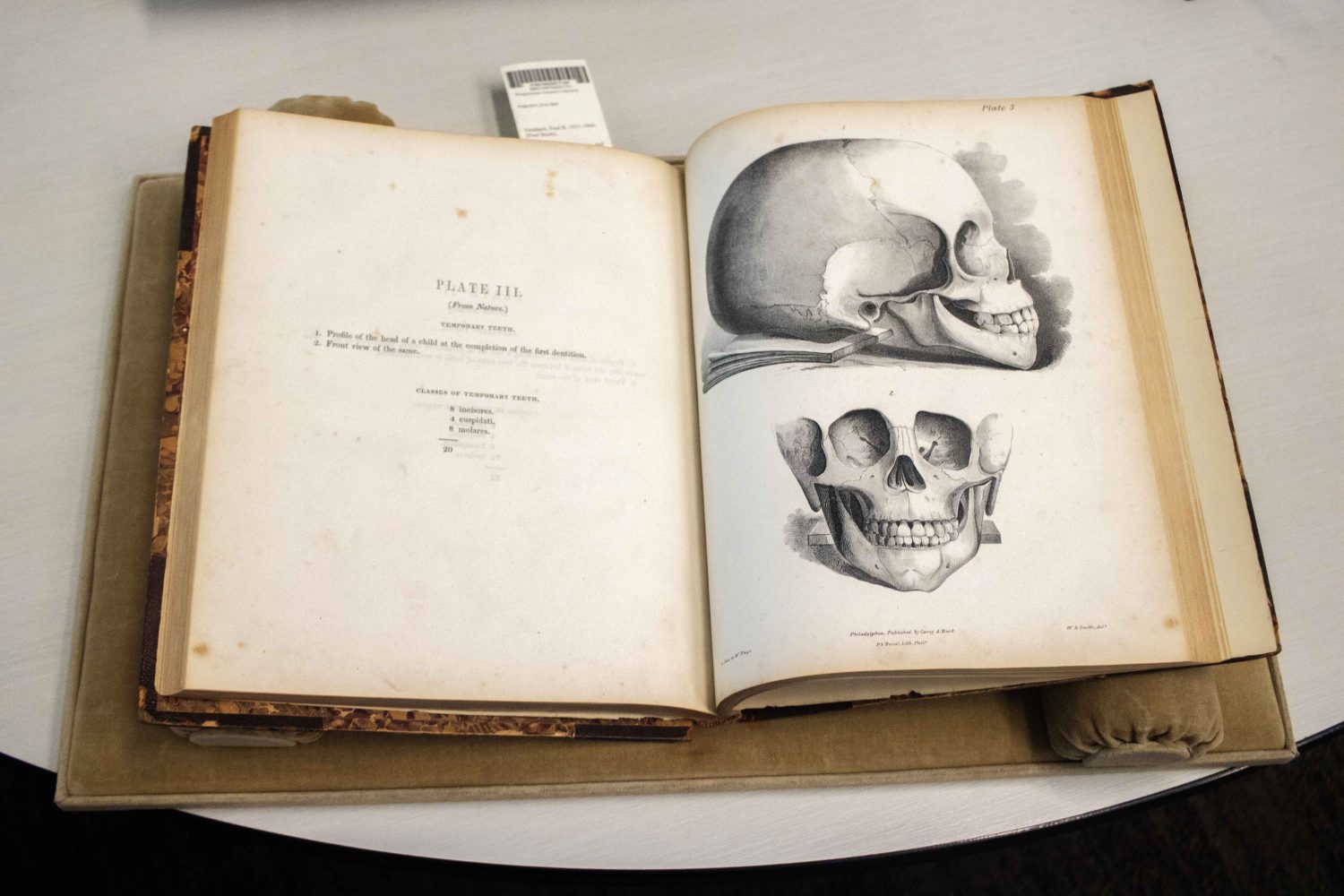

But the class changed when a cohort of visiting dental students from Germany came to campus as part of an international dental exchange program in 2021. The cohort was particularly fascinated by the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine (WHL), and its collection of related materials dating from 1430 to 1945.

Dr. Karin Quick, the Dental Public Health Division Director – alongside Nicole Theis-Mahon, the health sciences collection coordinator and liaison librarian to the School of Dentistry; the Wangensteen’s Curators Lois Hendrickson and Emily Beck and Public Services Supervisor Anna Opryszko; and Ai Miller, Library Assistant in Access and Information Services, and many others – saw an opportunity to reconceptualize the history of dentistry class.

“Collaborating with the Libraries has been such a valuable experience for me as an educator, and more importantly for our learners,” Quick said. “The expertise of each team member has added depth and prompted critical thinking among students helping them connect the past with their present and to envision the future.”

A rare book from the Wangensteen Historical Library shows drawings of the human skull. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

By encouraging first-year students to interact with rare books and artifacts directly, they can actively explore historical thoughts, ideas, and practices. The team worked for around five months to plan the 2022 version of the class. In 2023, the class required between six and eight months of planning.

Prior to class, students examined a StoryMap timeline of dental history ranging from 1723 to present day and read the article “What Should Oral Health Professionals Know in 2040: Executive Summary” by Jane Weintraub.

During the class, students rotate in small groups to various tables and topics stationed around the room. Each table displays historical texts and artifacts related to one of five dedicated themes:

- Oral and systemic health

- Diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Aesthetics and esthetics

- Technology and treatments, and

- Patient oral health and consumerism.

Facilitators at each station help guide students’ discussion and spark conversation.

“Studying an historical event or idea can highlight the ways that the frameworks of healthcare are interwoven with social determinants of health so they can develop strategies for creating better ways of treating patients,” explained WHL’s Assistant Curator Beck.

Having themes relevant to today’s issues and discussions are vital for students to contextualize dental history and understand what the future of the field might look like, Theis-Mahon explained.

For example, dental insurance is often not included with health insurance. A person’s systemic health and their oral health are considered separate, though each affects the other. When dentistry as a profession began, people questioned whether it should be separate, or if it should be another branch of medicine. Students are often surprised that this discussion stretches back to the late 1800s.

Two dental students read a book from The Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

“I really wanted students to make connections between the past and the history of their profession and think about where they are,” Theis-Mahon said. “Hopefully it’ll be impactful for them, and get them thinking about their education, and where they’re going to go as dental professionals.”

And so far it has. After the two-hour class, the team collected anonymous student feedback to further improve the class structure, and many students left the room thinking about how dentistry will evolve as time progresses.

First year dental students read primary documents relating to the history of dentistry. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

“One thing that I am excited to explore and is more of a broad question is what technological advancements dentistry will have in the future,” wrote one student. “Looking at the instruments and past methods today, made me realize how far dentistry has gone, and makes me wonder what will come in the future.”

Another student responded wanting to explore how to integrate systemic and oral health, so dentists are treated as medical specialists in the future.

“It seems like that idea was in the books from 100 years ago and also in our online reading for the future, but little has been done to make that a reality,” they wrote.

First year dental students examine different materials in a World Cafe classroom structure. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

The class is still changing based on student and facilitator feedback. Between the class’ 2022 and 2023 iterations, the team reduced the number of themes from six to five, added facilitators to each table, and held training sessions for the facilitators.

Some students have requested more artifacts, but the print texts have richer depth and insights, Theis-Mahon said. So they’re considering ways to direct students towards bigger picture questions when handling the artifacts.

For Theis-Mahon, who studied American history as an undergraduate at the U of M, this project demonstrates how the Libraries can collaborate with departments University-wide to create new pedagogical methods of teaching history, and how different ideas reemerge and are reinterpreted over the decades.

“I am really excited about this class. … I finally get to teach history in a way that I’ve always wanted to, and it’s in dentistry. I never thought that could happen. So that’s just been amazing,” Theis-Mahon said. “This is a really great way to show how liaison librarians can work with rare book collections and faculty to present historical context.”

Staff at The Wangensteen Historical Library, the Health Sciences Library, and the School of Dentistry pose for a portrait. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

And it’s clear that tomorrow’s future dental practitioners enjoy it too.

“I really enjoyed this experience and thought it was very insightful,” another student wrote. “It was a great way to begin thinking about the impact dentistry has on the world, as well as the impact the world has on dentistry!”