By Adria Carpenter

Men and boys wearing Indian headbands and feathers shaking hands, created between 1940 and 1969. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

The tribe would meet at each other’s homes, a small group of fathers and sons, “big braves and little braves.” The chief would open the ceremony. The rainmaker taught dances, and the tom tom beater played drums.

They’d hold pow-wows and summer camping trips, make feathered headdresses and bustles, and grow closer as father and son.

But here’s the problem. The “tribe” was white.

The YMCA Indian Guides was a father-son (later parent-child) development program, intended to help stereotypical stern fathers form real, authentic bonds with their children.

“Playing Indian” was the social lubricant and framework to foster those relationships, said Ryan Bean, archivist at the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

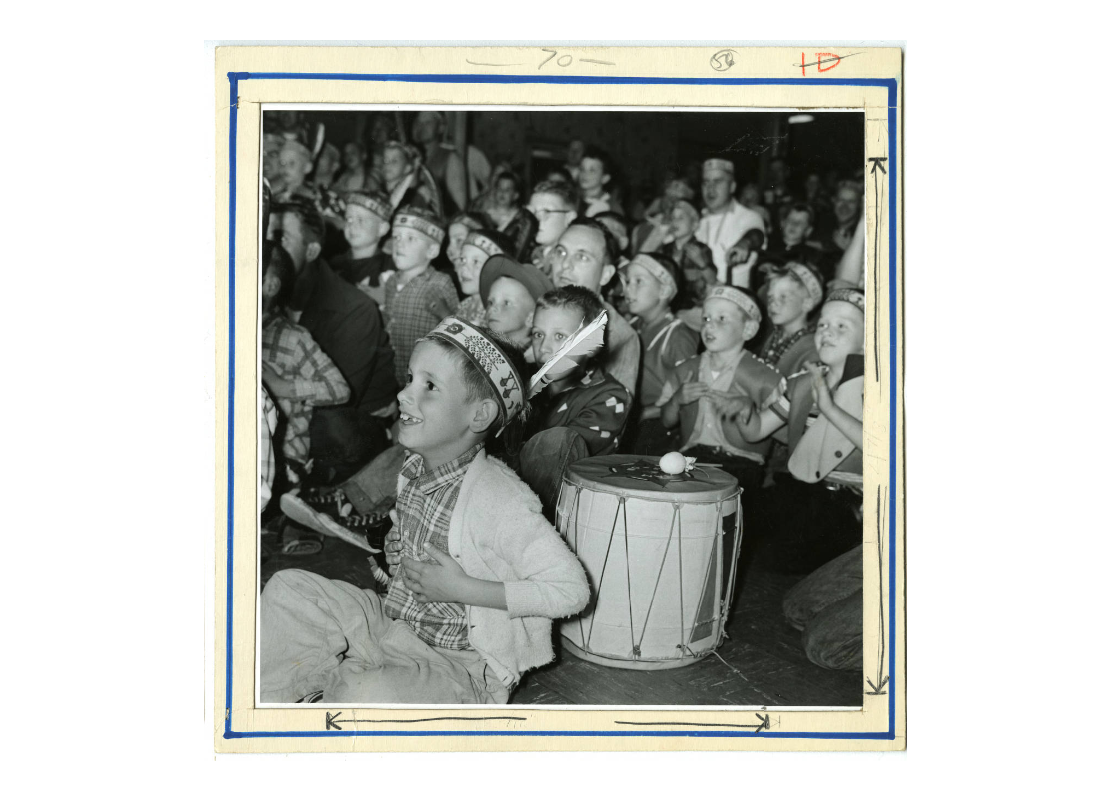

Boys with Indian Guides headbands and feathers seated on the floor with a drum, sometime between 1950 and 1970. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

“What’s sad is some of these fathers couldn’t tell their children that they loved them, that they were proud of them. But when they pretended to be like Grey Bear, then Grey Bear could tell Little Wolf that I’m proud of you,” Bean said.

“That’s why it was so successful. It practically guaranteed if you did this, your children would love you, which is a pretty powerful value proposition.”

Bean and co-author Paul Hillmer, a professor of American history at Concordia University in St. Paul, recently published the book “Inappropriation: The Contested Legacy of Y-Indian Guides,” which examines the program’s 77-year history and how it misrepresented American Indians.

“It was the book that I’ve been waiting for, and it was so wonderful to read,” said Kristen Spronz, the diversity and inclusion manager at the YMCA of the Rockies in Estes Park and Granby, Colorado. “When I got my copy of it, I had to buy another one because I highlighted pretty much every sentence.”

What were Y-Indian Guides?

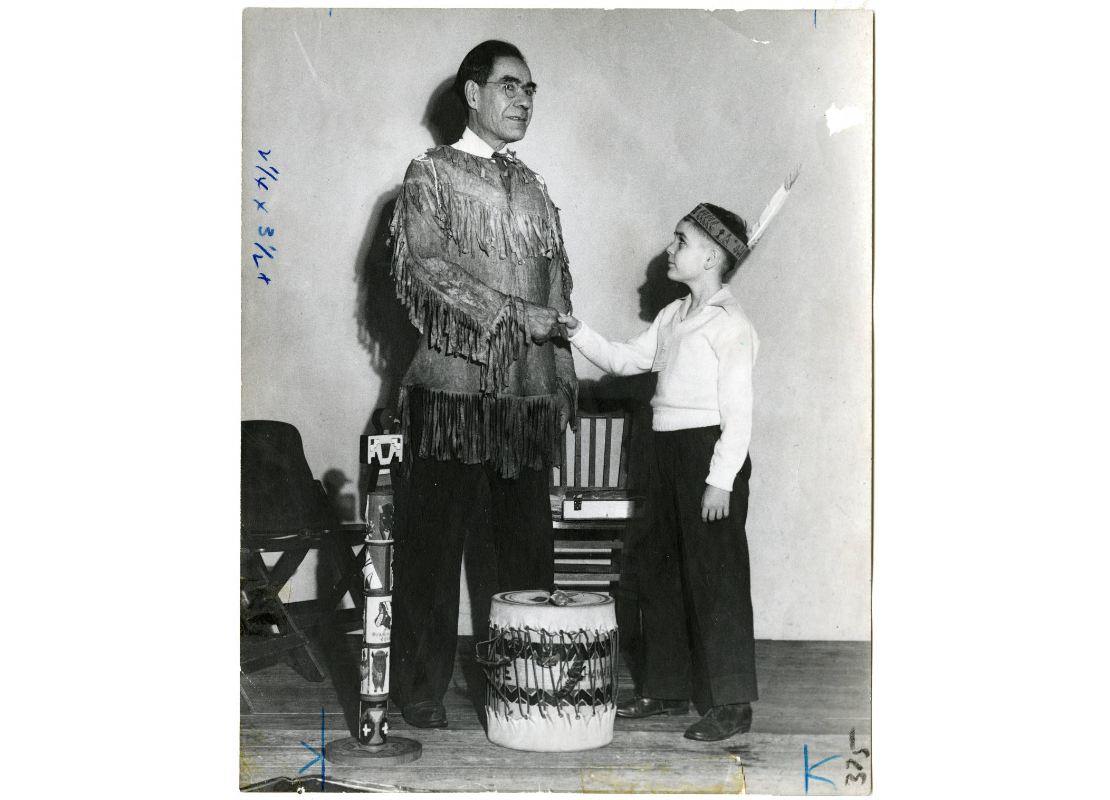

Y-Indian Guides were created in 1926 by two friends, Joe Friday of the Temagami First Nation in Ontario, Canada, and Harold Keltner of the St. Louis YMCA. The program was based on Friday’s own adolescent mixed with generic Christian values, like loving the “sacred circle of the family,” “love thy neighbor as thyself,” and “seek and preserve the beauty of the Great Spirit.”

“They would do their little theatrics … They’d play a game. They’d tell a story with an Indigenous candy wrapper put around it,” Bean said. “Mom would come with snacks at the end, and they’d go home and call it a day.”

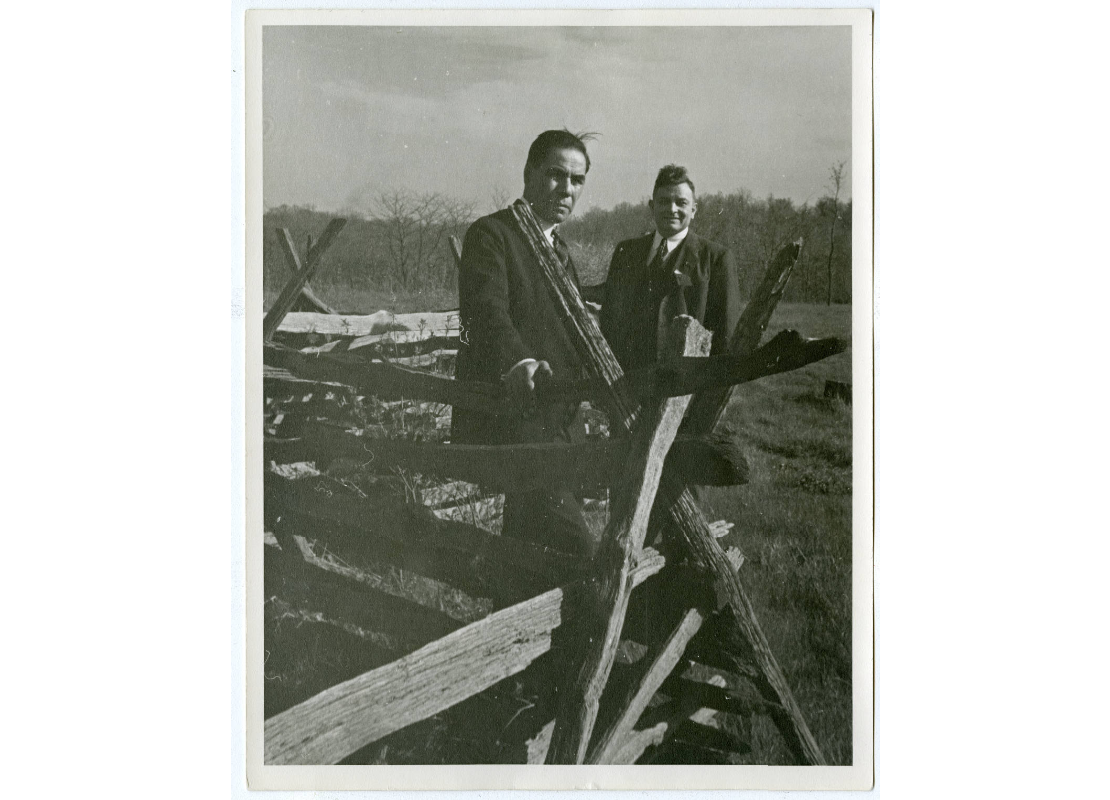

Joe Friday and Harold S. Keltner, YMCA Indian Guides founders, stand next to a split rail fence, between 1920 and 1949. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

Each “tribe” had around six to nine fathers and their children — usually boys ages 9 to 11, some as young as 6. To participate, the families must have YMCA memberships and use its approved materials, like a headband, manual, and pin for the father, and a headband and emblem for the son.

The “chief” was the tribe’s leader, the “tallykeeper” maintained the tribe’s activity records, and the “wampum bearer” oversaw the financial records. The aforementioned “tom tom beater” played drums during meetings, and the “little runner” did errands like collecting and distributing materials.

Joe Friday, Y Indian Guides co-founder, and a young boy in American Indian outfits shaking hands over a drum next to a small totem pole, sometime between 1920 and 1949. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

Some “tribes” also had “birch bark readers,” who researched Indian history and culture; the “moccasin maker,” who was responsible for the Indian costumes and clothing; “the chanter,” who taught Indian songs and chants; “the trailblazer” who taught Indian lore and stories; and so on.

“It was really driven home for me throughout the book that this was just an outdoor-based nature program where you got to engage with your children, and then we added cultural appropriation elements, which is just wild to me,” Spronz said.

‘Playing Indian’

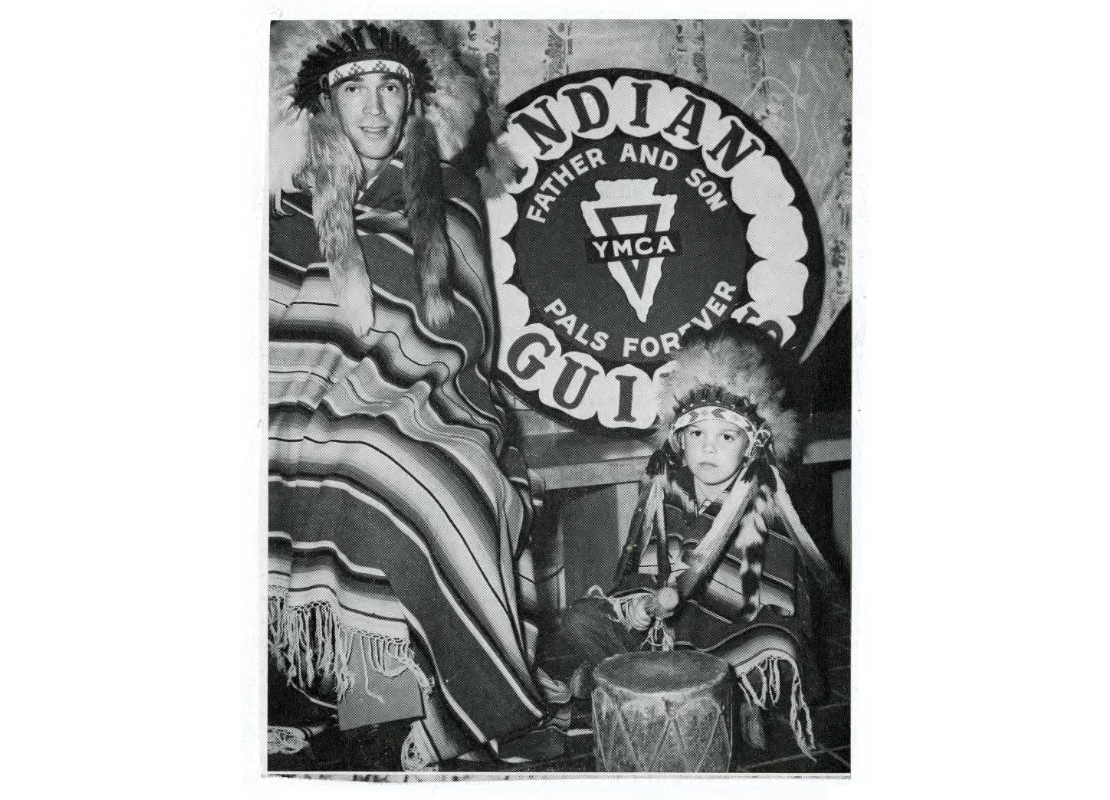

Besides helping fathers become teachers, counselors, and friends to their sons — with the slogan “Pals Forever” — the initial version of Y-Indian Guides was meant to educate people about Indigenous culture. But over time, the Indian theatrics became more cartoonish and stereotypical.

A man and a boy wearing Indian headdresses and blankets in front of a sign with the YMCA Indian Guides slogan, “father and son, pals forever,” created between 1930 and 1959. The boy is beating a drum. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

“It gets so lampoonish and so over the top. In the end, some groups are being banned from military bases cause these dads are getting so pissed drunk that they’re getting into fights,” Bean said.

And the educational elements were watered down, he explained. There’s a clear difference between learning about the history of ancestral lands and the people who lived there, and learning how to make a totem pole, for example.

A man and four boys at a work bench carving wood, painting, and using a ruler, photographed between

1930 and 1939. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

The program also grew more commercialized. Instead of father and son working for months to make a headdress, they could buy a kit and complete it in a few hours, or simply buy a headdress outright.

“There’s this confusion between the tool and the intent. The intent is to bring them together. The headdress is just the tool. Well now it’s just the tool, so I look like a badass chief,” he said. “It’s this commercialization of that space that hollows it out.”

The rise of Y-Indian Guides…

Despite its casual misappropriation of Indigenous cultures and reliance on stereotypes, Y-Indian Guides was widely popular nationwide. At its peak in the 1960s, it had a quarter million participants annually, including Disney’s Michael Eisner.

The first Y-Indian Guide “tribes” in Minneapolis appeared in 1947 and quickly became one of the fastest growing programs of the Minneapolis YMCA’s history, with information and advertisements circulating in local elementary schools during the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Minneapolis YMCA Minnetonka branch Indian Guides program father and son Good Friday breakfast at the Grace Lutheran Church in Deephaven, Minnesota, 1960. On the back of the photo there is a note, “150 in attendance. Weather good. Facilities crowded.” Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

“It’s almost a flip of a coin of people who did it or, in relation with somebody who did it, and people who had never heard of it,” Bean said.

At the program’s height, there were 250 Y-Indian Guide groups from eight local branches, and over 5,000 participating fathers and sons in Minneapolis. Even Bean’s wife participated in the program with her dad, though she doesn’t remember any Native sheen cast over the activities.

… and its fall

The program’s Indian elements began to phase out throughout the ’70s to early 2000s, due to mounting criticisms of cultural appropriation.

Today, the father-son program — rebranded as “Y-Adventure Guides” or “Y-Voyageurs” — has almost disappeared, eclipsed by the father-daughter Y-Princesses Program, originally called “Y-Indian Princesses,” which remains relatively popular in some pockets of the country.

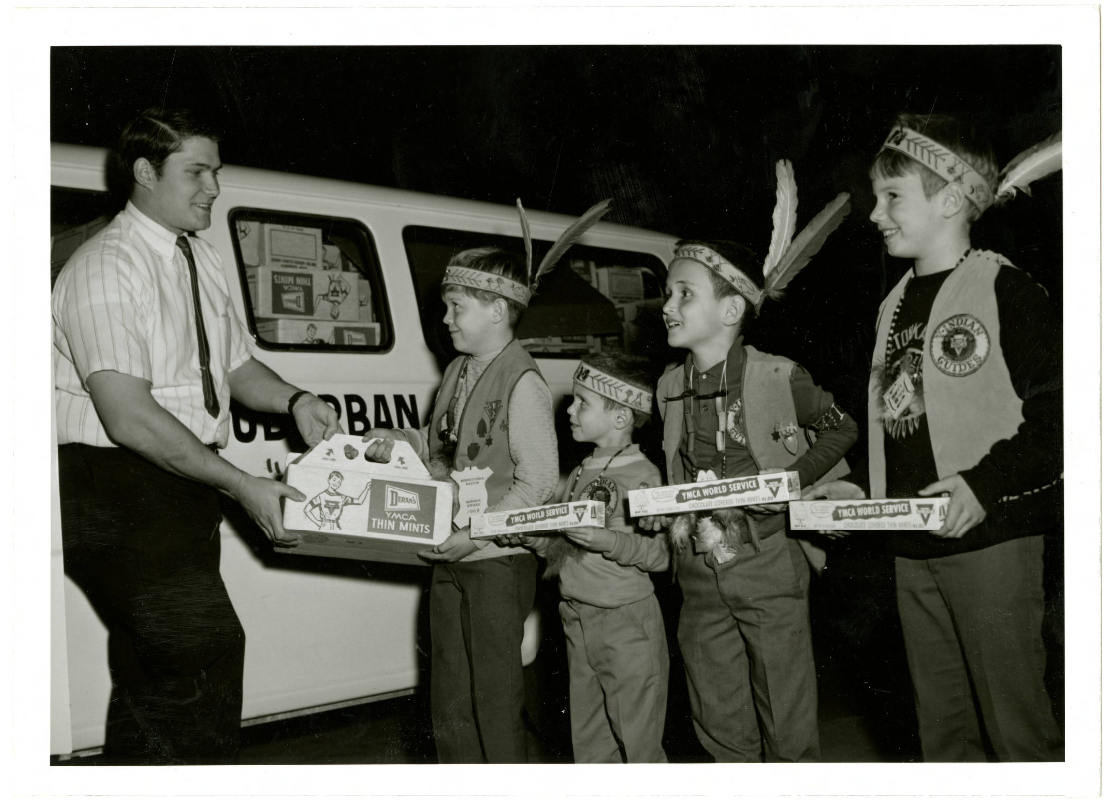

West Suburban Family Branch program director, Bill Strickland, passing out YMCA Thin Mints boxes to Indian Guide youth for their candy sale fundraiser, Minnetonka, Minnesota, 1969-1975. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

Jenny Miller, director of equity and leadership development at the YMCA of the North in Minneapolis, became a team member shortly after the rebrand to Y-Adventure Guides in the 2000s, and she was surprised that there was resistance changing the program.

“It was so obvious for it to be — well never started — but ended in like the ‘50s. Like we’re still having this conversation?” said Miller, a Brooklyn Center-native who has worked at the Y for 15 years. “It’s just wild to me.”

Y-Indian Guides were already dying off prior to the rebrand as American culture shifted and families found infinite other ways to spend time together.

Backlash to the backlash

But while some YMCAs removed the Indigenous elements from the program, others doubled down or split off.

“I’m part of facilitating learning experiences for teams, and there’s a lot of resistance from folks that have been with the organization for a long time,” Miller explained. “Even the idea of like, ‘We’re not really the YMCA, we’re the Y-Indian Guides over here. So just leave us alone, but give us resources when we need it.’ This mental model is still present today.” .

Participating fathers typically fell into one of two camps: those that appreciated the program as a readymade activity and treated it casually, and the diehards who latched onto the program as a necessary tool for communicating and connecting with their children.

For the diehards, any criticism of the program’s Indigenous pageantry was an affront to the loving relationship with their child, though in reality it was criticism of the methods used to form those bonds.

Men and boys wearing Indian headbands and feathers sitting in a booth with a sign reading “Seeing Stars with the Pawnees.” Behind them are diagrams of constellations, created by Nolte, A. J. sometime between 1930 and 1959. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

“While this isn’t true for everybody, there’s an overwhelming theme that if your culture is connected to white culture, it’s almost like this dissonance,” Miller said. “Like it’s too painful to reconcile with what has happened for so long that it’s easier for the mind to try to justify why things are fine.”

With increased criticisms of appropriation, some groups reacted by making the program more authentic and realistic.

“It’s just like, ‘We’ll take Indian out of Indian Guides, and just keep running with the program. You’re like, ‘Well wait a minute.’ It doesn’t solve the vastness of the issues that come with this,” Miller said.

What’s the big deal?

Bean argues that these authenticity revisions miss the point. The Y-Indian Guide program is not for the benefit of Indigenous people. It’s a self-serving exercise.

“To what end are predominantly white people using a non-white culture for the benefit of exclusively white people?” Bean said. “That’s the dynamic that I am scrutinizing here. I’m less curious about being authentic because to me, it’s authentic to what end?”

Fathers and sons in the Y Indian Guides program with headbands, small totem pole, a drum and other objects on a table, between 1930 and 1949. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

One common excuse people offer is “what’s the big deal?”

Paraphrasing Dr. Steve Long-Nguyen Robbins, imagine a world where Christians are a small minority, Bean said. And before football games, the non-Christian majority reenact the crucifixion of Christ. And when they score touchdowns, they make a cross sign and act out communion.

That would be disrespectful and harmful to Christians, even if it was intended to honor them. But hey, what’s the big deal? Lighten up. Don’t be so politically correct, right?

“I think the book forces the reader to have to sit with this idea of what is really honoring a culture, what is really honoring an individual,” Miller said.

Serving all people, not just white people

In the six months following its publication, “Inappropriation” is already changing the YMCA community and helping the organization reckon with its history and fulfill the promise of its mission.

Since she first got a copy, Miller has been “obsessed” with Bean’s book.

“He is awesome, and he’s so knowledgeable from a historical lens,” she said. “It was like, ‘Yes, this is just what I need to give me even more context and language to what I’m feeling.’”

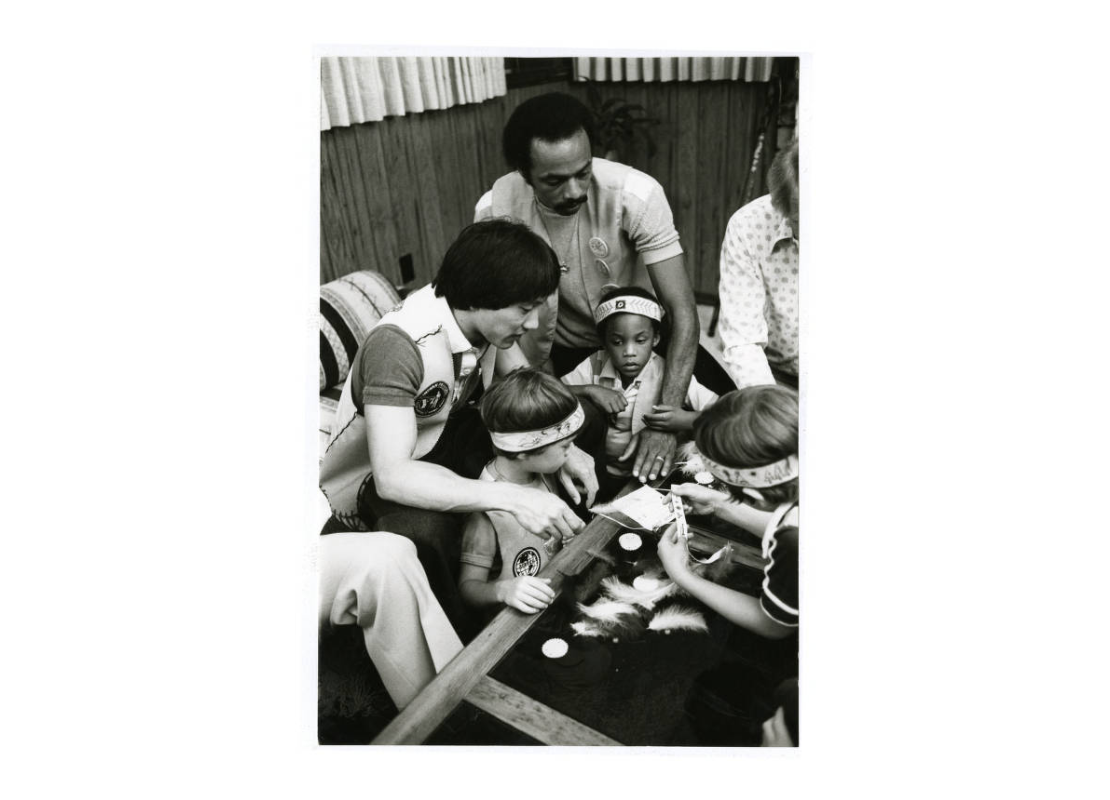

Men and boys gathered around a table with feathers and other supplies to make headbands, in 1979. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

For a while, Miller was one of the few Y leaders to have Indigenous people on staff at the YMCA of the North. And since reading the book. Miller and her fellow team members made intentional efforts to hire multiple people of diverse backgrounds, and not just hire one person who’s expected to solve every problem for them.

They’ve also started holding town halls for team members to listen and learn from the community. Miller helped develop a curriculum called Leading with Excellence and Equity, instigating personal and organizational transformations, and the YMCA of the North now has an Equity Advisory Council, the first of its kind.

“There’s still a lot of work that needs to be done,” she said.

‘Who we say we are’

At the YMCA of the Rockies, Spronz and her team all bought copies of the book for a group study. They’re now evaluating cultural appropriation across the entire organization. The team is changing the names of certain buildings and cabins, educating people about those names, and explaining why the change was necessary.

“His book was the tool that we needed because once you know better, you have to do better,” she said. “The education that came from Ryan’s book was the catalyst to really evaluating everything in our association related to appropriation.”

Boys and men wearing Indian headbands, feather headdresses, and beads. One boy sits on the lap of a man wearing a large feather headdress, sometime between 1950 and 1959. Courtesy of the Kautz Family YMCA Archives.

Spronz, from New Jersey, moved to Granby, Colorado, and began working at the YMCA. She thought it would be a temporary stop on her way to Denver, but now she’s been there for seven years.

“Very quickly I was connected to the mission of the Y, and what that actually looked like, and what that meant,” Spronz said. “I like that we are an organization committed to serving all people, and I think that we’re not there yet, so we have so much untapped potential to live up to who we say we are.”

A tale of two Ys

While Bean criticizes Y-Indian Guides, he’s empathetic to parents who participated in the program, formed strong relationships with their kids, and have loving memories of that time. While chipping away at the book, Bean became a father, his own father nearly passed, and his co-author lost his father and father-in-law.

“It did change how I understood it. I was able to appreciate, at a much more grounded level, why parents would do this,” he said.

Bean hopes that people see the book as a nuanced and loving analysis of two conflicting truths, that Y-Indian Guides were great in some respects, and horrible in others.

“Organizations like the Y can bring people into a community and can do a lot of really amazing things. But it’s really critical to reflect on the methods that are used, and to make sure we’re intentional on how our tools match our intent,” he said.