In urbanist circles, Minnesota’s reputation stretches as far as North Carolina. That’s where Kelly Rogers, a young housing justice advocate, first felt drawn to the Twin Cities.

Relative to other Midwestern metropolitan areas, the Twin Cities are spearheading enticing urbanist ideas, like the Minneapolis 2040 plan, greenway bicycle network, or projects like Mapping Prejudice.

But more importantly, these aren’t just pipe dreams. Minnesota attracts people with the expertise, practical skills, and willpower to make these ideas reality. People like Rogers.

“This is where a lot of the theoretical urbanism that you hear about is actually happening. And it’s not perfect, but they’re willing to try different things,” Rogers said. “It made me wonder, ‘What else could be done?’”

Community organizing in New York City

After graduating from high school, Rogers decided to move from North Carolina to New York City. She started working for Urban Outfitters, babysitting, and picked up other side jobs in-between.

Rogers hadn’t been exposed to many progressive political movements in her hometown, though she had always been more interested in social justice than her peers. In New York, she joined community organizing efforts, starting oddly enough, with Twitter and gun control advocacy.

Following the 2018 Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida — which remains the deadliest mass shooting in a high school in United States history — survivors organized the March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C., advocating for stronger gun control legislation.

As marches and protests spread throughout the country, Rogers grabbed the Twitter handle for “March for Our Lives, New York City.” Other student organizers contacted her for the handle, and seeing an opportunity to collaborate, she offered to work together.

A month after the Parkland shooting, Rogers became the creative director of March for Our Lives NYC and spoke at the protest, which had between 150,000-200,000 people in attendance. Following the rally, she was hired as an associate producer for the production company Women Rising and served as a line producer for its film, “WE GO HIGHER: A Documentary of Hope from the 9/11 Kids.”

How to build a better city

“At Mapping Prejudice, we get the chance to work with historians and geographers and cartographers and lawyers. It’s just such an intersection of really talented people.”

—Kelly Rogers

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Rogers moved back to North Carolina and discovered a different political climate than the one she left behind. Protests following George Floyd’s murder changed the conversation around police brutality and other social issues in her hometown.

Using her local experience and newfound passion for activism via storytelling, Rogers began advocating for housing equality and working with a low income housing community. Through her work, she discovered Mapping Prejudice, a project at the University of Minnesota Libraries that mapped racial covenants in Hennepin and Ramsey counties.

Mapping Prejudice’s resources helped illustrate systemic racism in a material, less theoretical manner. It was perfect for laymen, especially those in the South who can be defensive about the region’s racist history and quickly point to Jim Crow policies in the Northeast and Midwest.

In 2022, Rogers decided to pursue an undergraduate degree in urban studies. The University of Minnesota seemed like a logical choice, but her actual decision to apply felt almost random; she had never even visited the Twin Cities before. After speaking with Paula Pentel, advisor for the urban studies program, Rogers became first convinced, then excited.

The stories buried under racial covenants

Earlier this year, Rogers met Kristen Delegrad, one of the co-founders of Mapping Prejudice, when the team visited her class. After listening to their presentation, Rogers wanted to get involved.

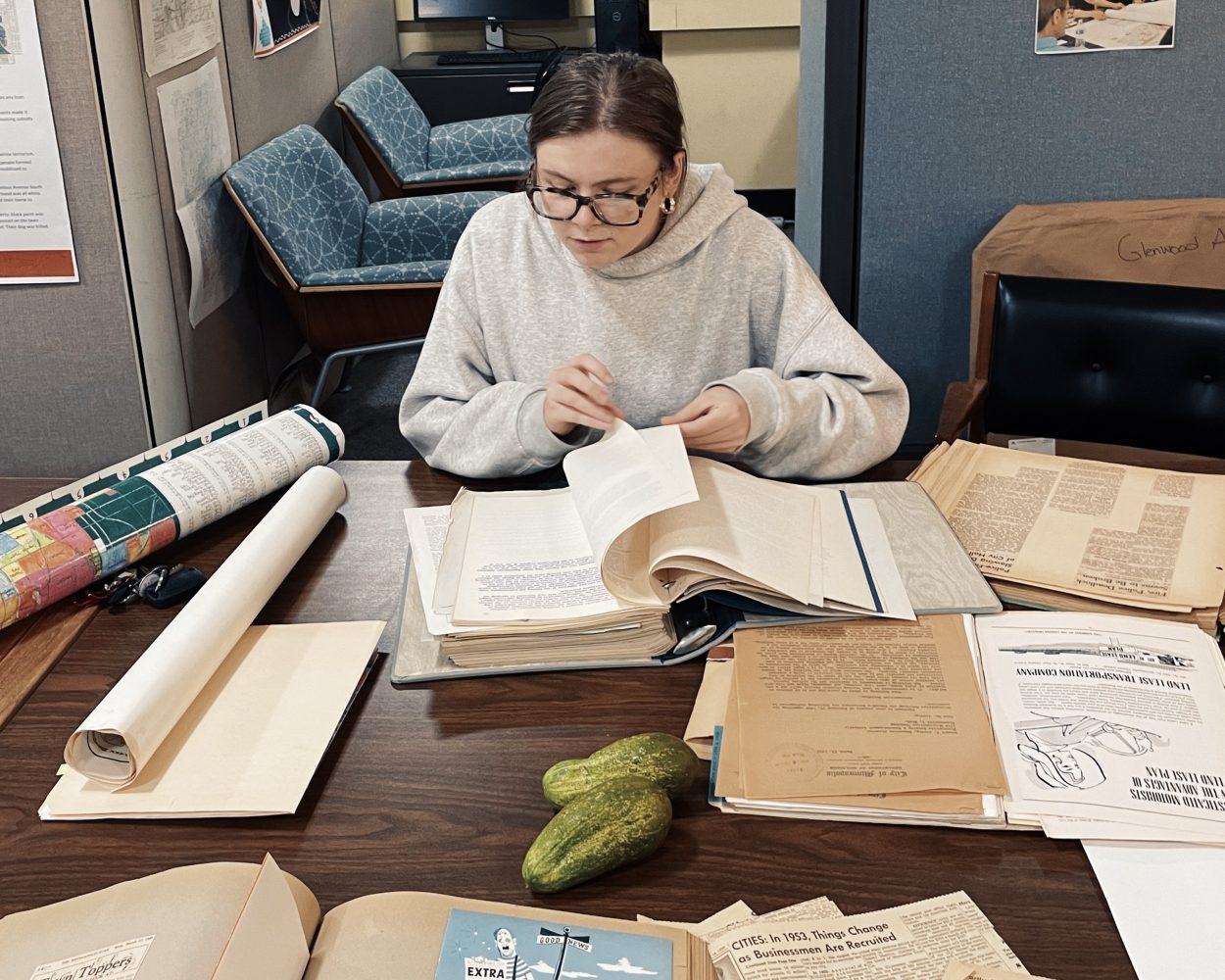

Kelly Rogers

In June, she joined the team as the communications manager, where she creates materials for social media (like infographics and calls-to-action), helps manage the Mapping Prejudice website, and edits the team’s writings. She makes their information and resources accessible, shareable, and approachable for everyone in the community.

Rogers loves Mapping Prejudice’s interdisciplinary, “Swiss Army Knife” approach. The team’s talents and interests aren’t confined to a single box. And the same is true for the urban studies department, she said.

“You can get the job done and have everyone contributing in a way that they are the most qualified to do. It makes the work so much more fun. It makes the work better too,” Rogers said. “At Mapping Prejudice, we get the chance to work with historians and geographers and cartographers and lawyers. It’s just such an intersection of really talented people.”

Alongside her coworker, Hannah Belyn, Rogers is currently working on a podcast, tentatively titled “Stories from the Map,” which will relay personal stories that were excavated by the team during the process of mapping racial covenants.

“For the people that are here, I think it’ll be really interesting because a lot of the stories take place in neighborhoods that obviously still exist,” she said. “But it’s also just trying to widen that reach again, and make sure that there’s as many modalities available to people that are interested in the work as possible.”

It’s marathons all the way down

Rogers likes to keep busy. Between classes, she’s an opinions columnist for The Minnesota Daily, where she writes about transportation and housing, of course. But she’s also covered campus communist organizations, literacy and writing in prisons, and whether the government is hiding the existence of aliens.

“I’m 24, so I feel ancient compared to a lot of the kids in my classes. I think [writing has] connected me to the university in a really unique way that I was sort of missing when I first started here,” Rogers said.

The publishing grind has pushed her to write precisely, actively, and intentionally, but it comes with its own stressors. Before every article hits the web, she feels an inherent panic and regret.

“And just the paralyzing knowledge that you’re being perceived. Oh my God, I’m not used to that for sure. When people will tell you they read you, and I’m like, “Ahh, don’t tell me that!’” she said. “I definitely invite the chaos, but I’m really not used to having my government name attached to it.”