Portrait of Dora Zaidenweber by Spanish artist Félix de la Concha for his series “Portraying Memories: Portraits and Conversations with Survivors of the Shoah.” University of Minnesota, Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, UMedia.

April 15, 1945 was a bright and sunny day at the Bergen-Belsen concentration, which felt ironic to Dora Zaidenweber. The camp itself was desperate and hellish, on the verge of collapse from starvation and an epidemic of spotted typhus.

Zaidenweber, from Radom, Poland, was just 15 years old when Germany invaded her home country. And for the next six years, she lived under the shadow of death and uncertainty – from the Radom ghetto to Auschwitz and finally Bergen-Belsen – until that bright, sunny day in April, when the British Army liberated the camp.

Zaidenweber eventually reunited with her immediate family, and in 1950 they relocated to Minnesota. By the early ’50s, they were among some 1,300 survivors of the Holocaust who resettled in the state following the war.

Zaidenweber’s story is well-documented, but many other stories of Minnesota survivors – their lives before and during the Holocaust, the winding path of relocation, and what they faced in the state – have faded with time.

“We’re losing survivors, we’re losing that narrative, and students are increasingly unaware of the events of the Holocaust,” said Joe Eggers, interim director at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies (CHGS) at the University of Minnesota.

Zaidenweber herself passed away this past fall at age 99. To preserve these stories, the CHGS and the Upper Midwest Jewish Archives (UMJA) are working on Minnesota Shoah Stories, an interdisciplinary project that will collect materials relating to Minnesota survivors from different departments and archives on campus, and make them available in one cohesive project for educators and researchers.

Minnesota Shoah Stories

“We’re losing survivors, we’re losing that narrative, and students are increasingly unaware of the events of the Holocaust.”

— Joe Eggers, interim director at the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies (CHGS) at the University of Minnesota.

The idea for the project came when Meyer Weinshel, then the collections curation and outreach lead for CHGS, found a scrapbook in the center’s small collection which he felt belonged with UMJA instead.

Weinshel and UMJA Archivist Kate Dietrick began comparing notes to see what other overlapping materials the two collections had. They wanted to expand awareness of those connections and tell a deeper story about survivors who resettled in Minnesota, like Zaidenweber.

The project will have multiple phases, Dietrick said. Currently they’re in the collection phase, locating every scrap of information about Minnesota survivors and cataloging it into a database, and they’re planning to extend the database to include materials in other U of M archival collections in the coming months. So far, the database includes 176 survivors.

The second phase will create a digital humanities project, like mapping of every survivor, where they came from and how they came to Minnesota, or uplifting a few well-documented stories. The exact form of the project will be determined later, Dietrick said, but by this summer, they’re hoping to complete a story map about five survivors.

Eggers expects that the project will snowball to other institutions, organizations, and collections across the state.

“I don’t know if we’ll ever come up with an end date for this project, and that’s also really exciting because you’re always telling and sharing new stories,” Eggers said. “I think it’s a really incredible model of how the Libraries can work with researchers not only to support research, but also to produce really incredible work.”

What can we learn from Minnesota’s survivors?

CHGS has two primary goals, to support scholarship and to engage with K-12 educators. And very rarely do they have the opportunity to do both simultaneously. But this project will work in university lecture halls and classrooms throughout Minnesota.

“There is a real need to share these stories outside the University, but also to make it accessible for scholars and researchers,” Eggers said.

The project also coincides with a recent education mandate passed by the Minnesota Legislature, requiring schools to adopt Holocaust and genocide studies into the curricula for middle and high school students by the 2026-2027 academic year.

“There’s going to be a real push and real need for materials that students can relate to. Students will have that tangible way of seeing their history locally,” Eggers said. “We can say, ‘Look these are your neighbors, these people are here,” … and for me as an educator, that’s really what’s exciting.”

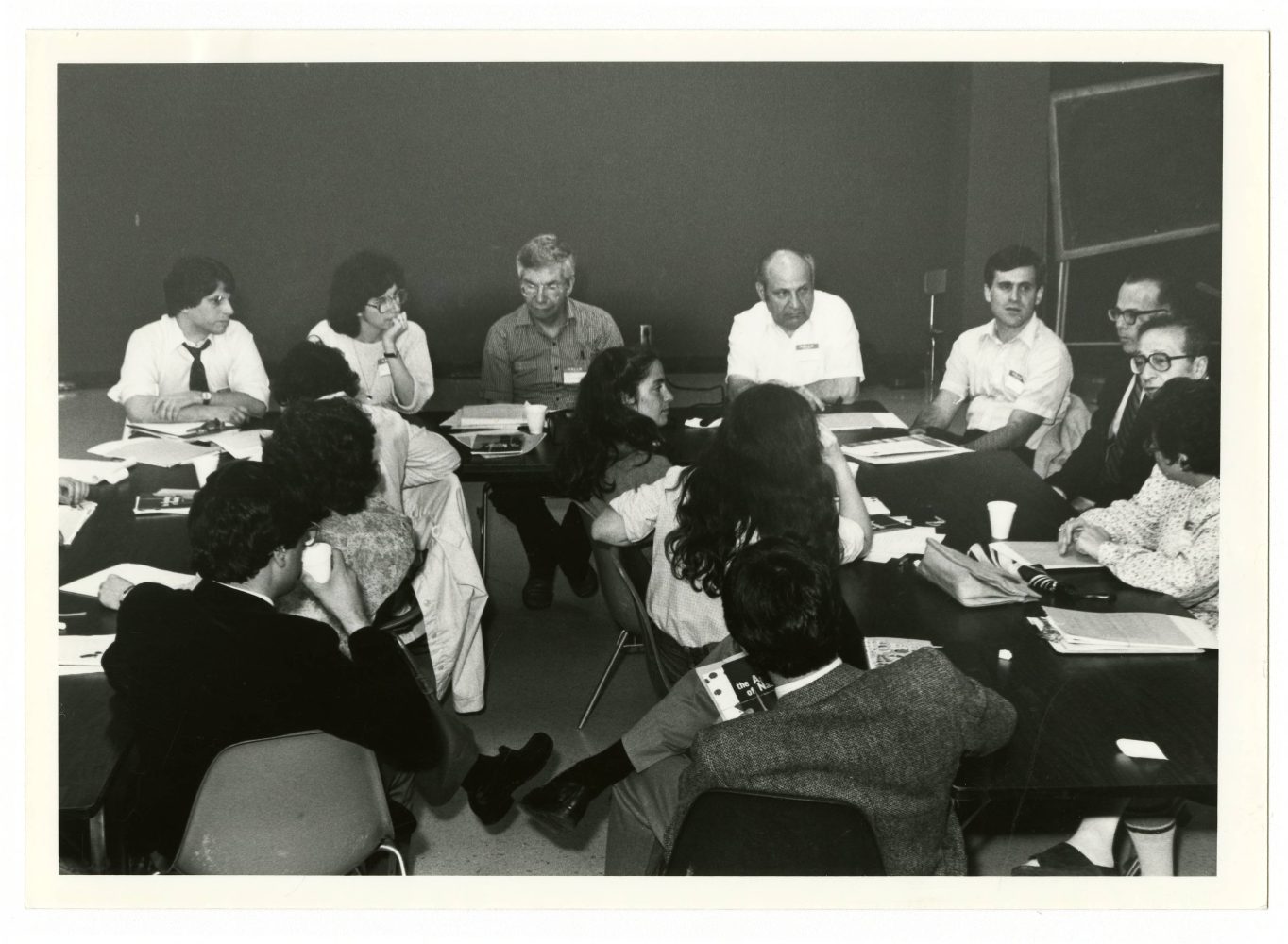

Group meeting during the Jewish Community Relations Council Holocaust Taping Project. University of Minnesota Libraries, Nathan and Theresa Berman Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, UMedia.

Dietrick believes the project will help people understand that despite happening an ocean away, the Holocaust had an impact on Minnesota history. The stories of survivors continued past 1945, through the displaced persons camps, through immigration to new countries, through the search for surviving family members, all the way here to Minnesota.

“Survivors continue to live their lives and are part of our community. And what can we learn from them?” Dietrick said.

This summer, the team is organizing a teacher’s workshop to showcase some of these materials and implement them into the classroom for students to use during research projects.

A more complete story

The project will allow the Upper Midwest Jewish Archives and the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies to provide a more in-depth look into a survivor’s story — rather than a surface level snapshot, and help researchers by gathering materials from multiple archives and collections into one place.

CHGS conducted a series of oral interviews with Zaidenweber, for example, and now the team can tether those interviews to Zaidenweber’s materials and papers housed in UMJA and the Immigration History Research Center Archives (IHRCA).

“The center has only a relatively small collection, and we can tell snippets,” Eggers said. “But working with UMJA and other archives, we can really tell a more complete story.”

Because of the forced upheaval of World War II, archives don’t often have boxes and boxes documenting the lives of survivors who resettled in America. Sometimes they only have a handful of items.

The Holocaust hasn’t historically been a collection priority for UMJA, since those materials were at times considered more suited to places like Holocaust-focused museums, but without actively searching, the archive has plenty of related materials, Dietrick said. So it’s been surprising to see what the team has uncovered in CHGS’ collection, and she expects researchers will be equally interested.

“There’s so many more names, there’s so many more pieces in there. All it takes is someone to start looking and uncovering,” Dietrick said.

Dietrick also hopes that as survivors and their loved ones pass away, the project will remind their family members to donate their materials to an archive – whether that’s UMJA, CHGS, or another archive – so those stories aren’t lost or forgotten.

After survival, there’s resilience

While many Holocaust narratives end at the liberation of the concentration camps, the story goes on.

Following World War II, hundreds of thousands of displaced persons were left without a linear path home, if home even existed. Many had no cities or countries to return to, and drifted between displaced persons camps, looking for family. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) helped administer relief and participated in repatriation efforts.

After liberation from the Bergen-Belsen camp, Zaidenweber stayed at an UNRRA camp in Heidelberg, Germany, for two weeks. She was transferred to Stuttgart and lived in a housing project until September 1950, when she emigrated to the United States with her husband, first to New York City and then to Minneapolis.

“The complexity of how people got to Minnesota is super interesting,” said Kathleen Ibe Berube, a research assistant at CHGS and doctoral student in the Department of German, Nordic, Slavic, and Dutch. “There’s also a much more complex story to tell with the antisemitism they faced in the U.S.”

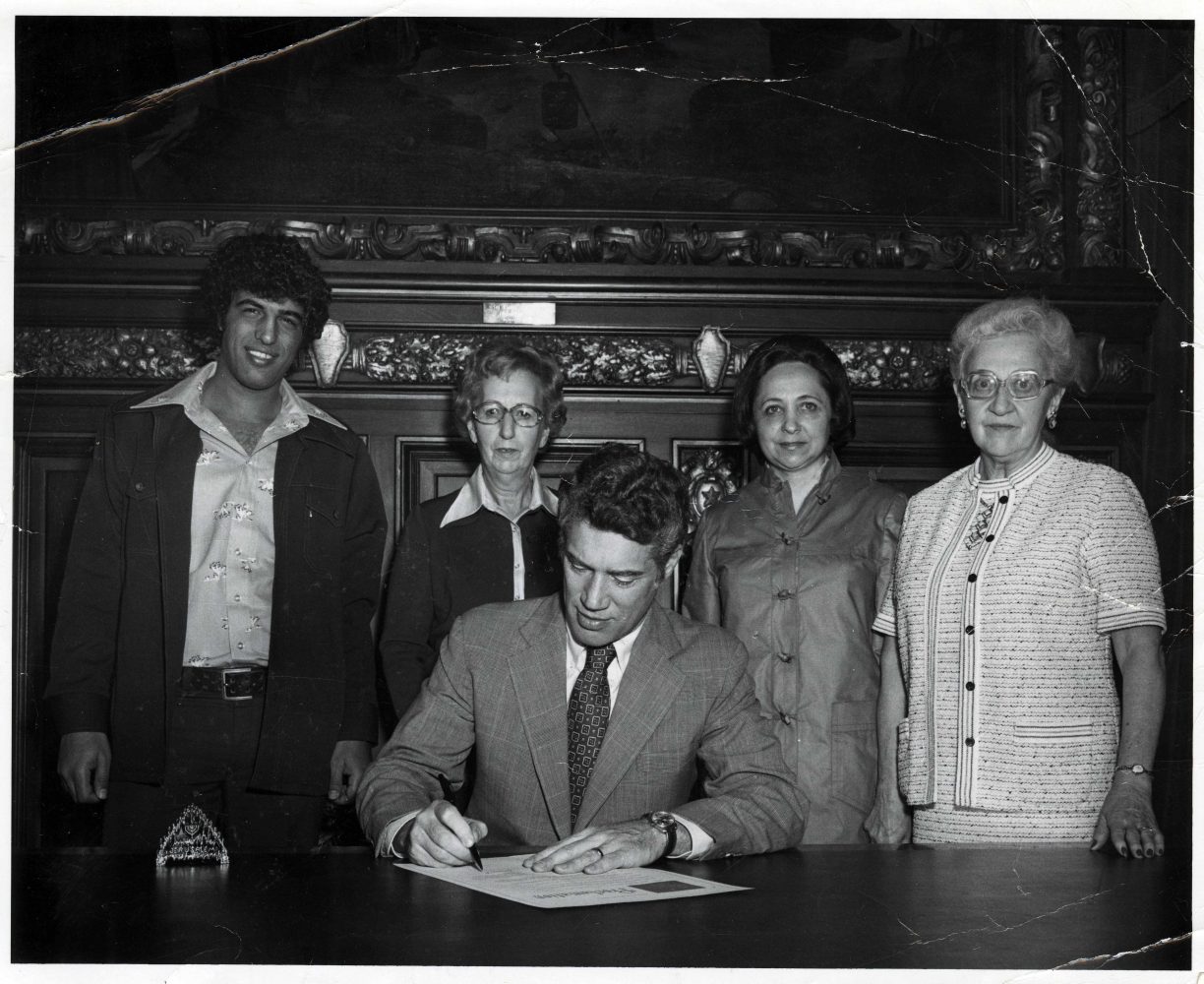

Governor Wendell Anderson signing Holocaust Day Proclamation in St. Paul, Minnesota. Included in the photograph: Ami Yemini, Ethel Levey, Felicia Weingarten, and Adeline Fremland. 1975 – 1977. University of Minnesota Libraries, Nathan and Theresa Berman Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, UMedia.

When Zaidenweber came to Minneapolis, it took at least five years before she had any American friends. Many didn’t see her as an equal, and they couldn’t comprehend her experiences in the Holocaust, or simply didn’t believe it.

Despite the antisemitism that many faced in Minnesota, many survivors found a community and home at the University of Minnesota, becoming students or professors, including Zaidenweber who studied economics.

Ibe Berube grew up in Germany and learned about the Holocaust at an early age. The project rests deep in her heart, especially now with rates of antisemitism and fascist sentiment rising in Germany and across the world, she said.

“Humanizing the Holocaust from the Minnesota perspective – and seeing the writing, the handwriting, the photographs – it’s just really deepened my understanding of all these different lives and the extent of what happened back then, but also how it continues to shape the present,” Ibe Berube said.

“Never again” means never again, and the team wants to remind people of that.

“When we’re talking about the past and especially the Holocaust, we get caught up in numbers and we really lose a sense of humanity,” Eggers said. “But these people have stories to share beyond just being a survivor of the Holocaust. And that really becomes a story of resilience.”