“History isn’t just about facts — at the college level, it’s about understanding how [historical narratives] are made,” said Dr. Katharine Gerbner, Associate Professor of History at the University of Minnesota and Faculty Coordinator for the University’s College in the Schools (CIS) partnership program.

Dr. Gerbner was addressing an audience of over 300 high school students gathered in Willey Hall on the University’s Twin Cities campus earlier this month. The students were all participants in the CIS program, which enables academically prepared juniors and seniors to earn college credits by taking U of M courses at their own high schools.

The CIS students traveled from across the state of Minnesota to the U of M campus for a day of immersive learning, including presentations on the role of primary sources in historical research, followed by visits to various archives and collections at the U of M Libraries for hands-on group activities.

Fittingly, the theme for the day’s events was “History and Archives.”

Dr. Katharine Gerbner provides opening remarks at the March 2024 College in the Schools event. (Photo/Carl Stover)

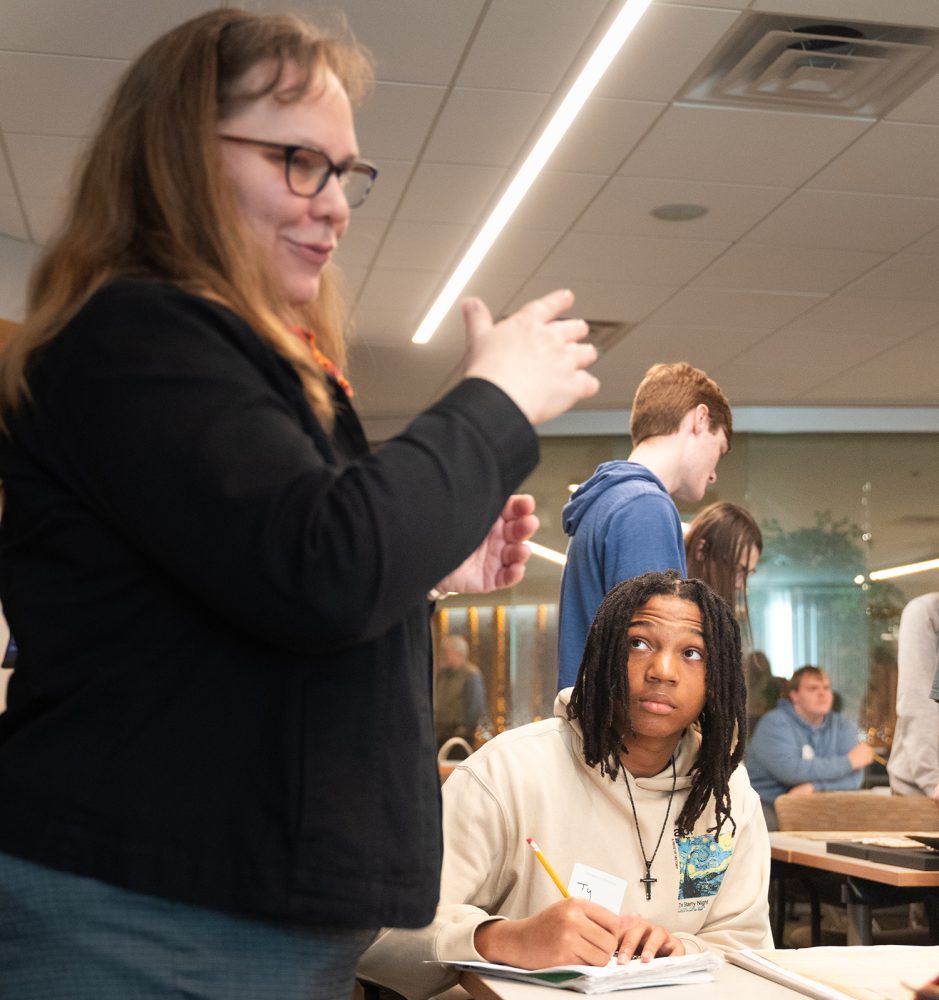

Jessica (left) and Elijah (right) from Richfield High School listen to the opening presentations at the March 2024 College in the Schools event. (Photo/Carl Stover)

Looking to the past in order to understand the present

Kirsten Delegard, Project Director for the Mapping Prejudice Project, kicked the morning off with a presentation on her team’s use of primary source materials in their historical research, including racial covenants found in property deeds across the state that prevented people who were not white from buying or occupying land.

Delegard emphasized the significance of not only tracking these historical materials, but interacting with them first hand.

“We want people to read these primary sources,” she said, “and to think about connections between past and present.”

In the Twin Cities today, for example, 75 percent of white families own their homes, compared to just 33% of Black families. For Mapping Prejudice, then, historical materials aren’t just tools for understanding the past — they also offer a critical framework for understanding the “intergenerational consequences” of systemic racism.

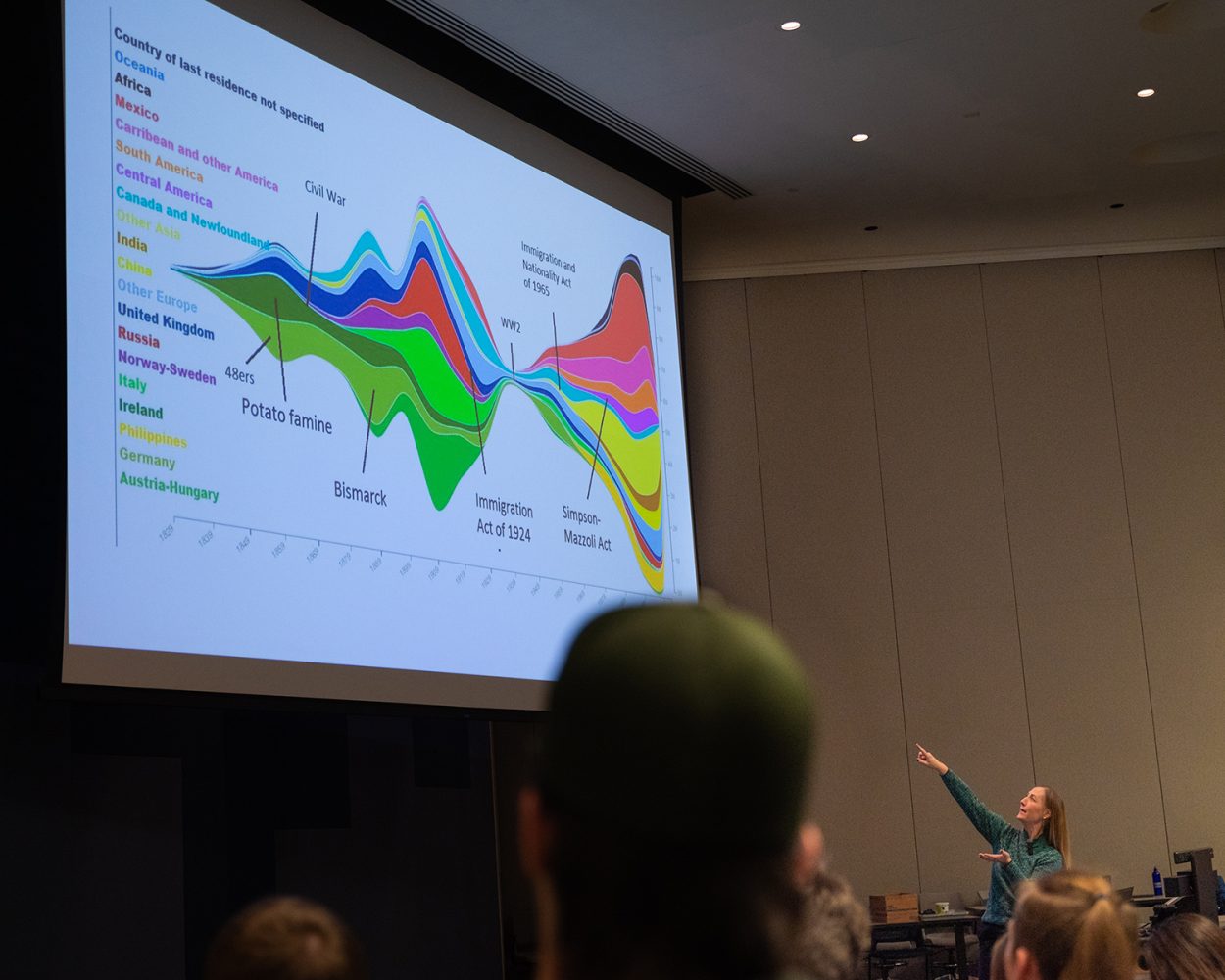

Michele Waslin, Interim Director of the Immigration History Research Center (IHRC), similarly challenged students to think critically about the role that history and historical research can play in understanding the present, as well as in making informed decisions about complex topics like immigration.

Waslin showed students primary source materials — including 19th century chromolithographs and advertisements — that reflected the nation’s conflicted attitudes towards immigrants throughout history. She also introduced students to the Immigrant Stories project, a digital archive of firsthand narratives from immigrants (and families of immigrants) from over 50 ethnic groups and 40 countries.

Kirsten Delegard, Project Director for the Mapping Prejudice Project, gives a talk at the March 2024 College in the Schools event. (Photo/Carl Stover)

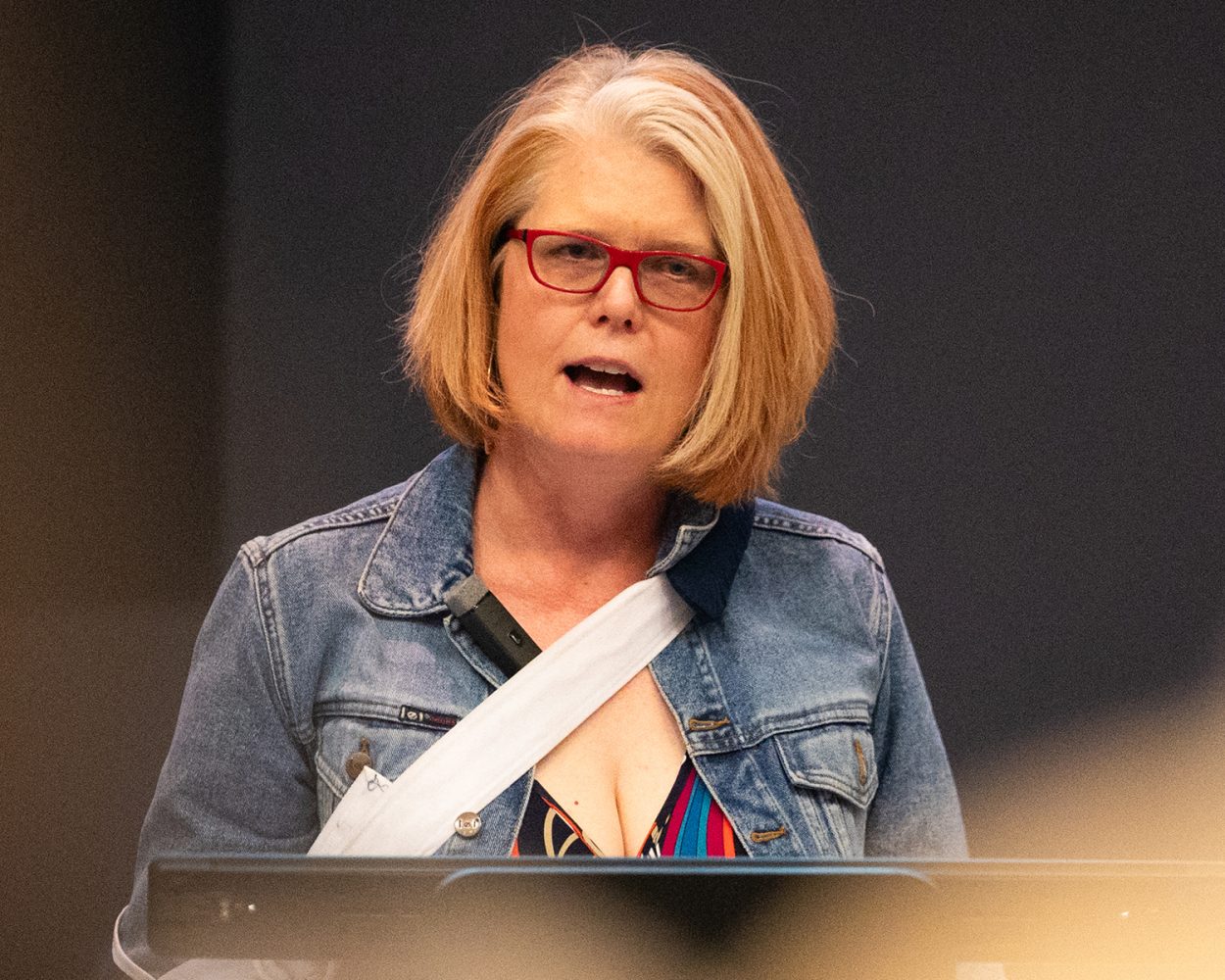

Michele Waslin, Interim Director of the Immigration History Research Center (IHRC), gives a talk at the March 2024 College in the Schools event. (Photo/Carl Stover)

Makenzie from Richfield High School studies archival materials from the Social Welfare History Archives. (Photo/Carl Stover)

Historians for a day

After the presentations, students split off into smaller groups to visit different archives and collections across the Libraries, including the Upper Midwest Jewish Archives, the University Archives, the Social Welfare History Archives, the Tretter Collection, the James Ford Bell Library, the Immigration History Research Center Archives, the Wilson Library General Collection, the Borchert Map Library, the Music Library, and the Wangensteen Historical Library.

“Archives and Special Collections routinely uses our collection materials for teaching classes,” noted Kris Kiesling, Director of Archives and Special Collections at the Libraries. “It’s a great experience for students of all ages to be able to see and handle rare and unique materials, but it’s especially true for high school students. We try to make history relevant to their own experiences.”

At Wilson Library, for example, students were exposed to six themed stations featuring everything from historic newspapers to enslaved people narratives to art and architecture catalogs. Paloma Barraza, History, Iberian, and Latin American Studies Librarian, created the stations and helped Dr. Gerbner to coordinate the event.

“The students learned about how scholars use primary source materials and had a chance to be historians for a day,” she explained.

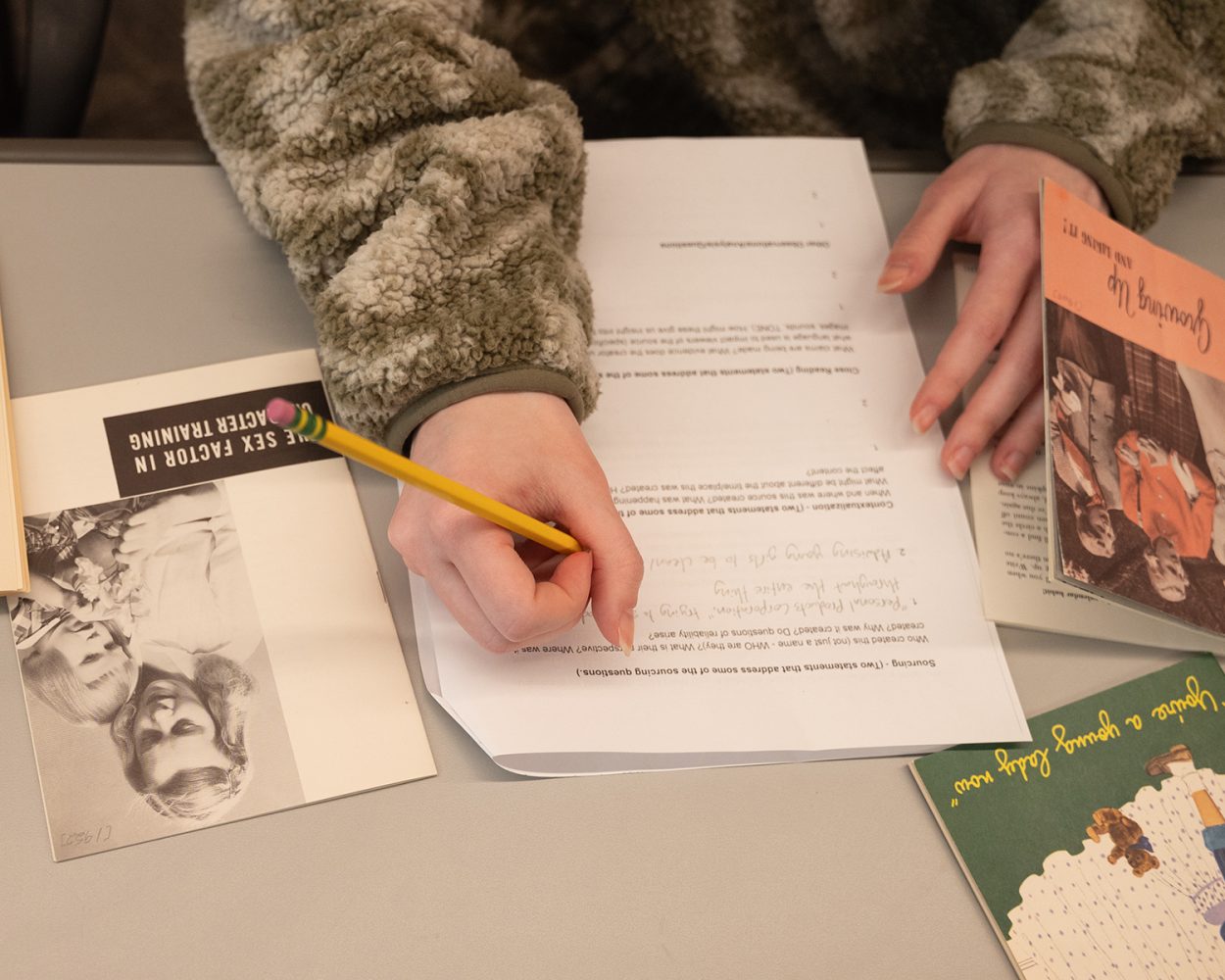

A student completes a source material activity, using resources from the Social Welfare History Archives. (Photo/Carl Stover)

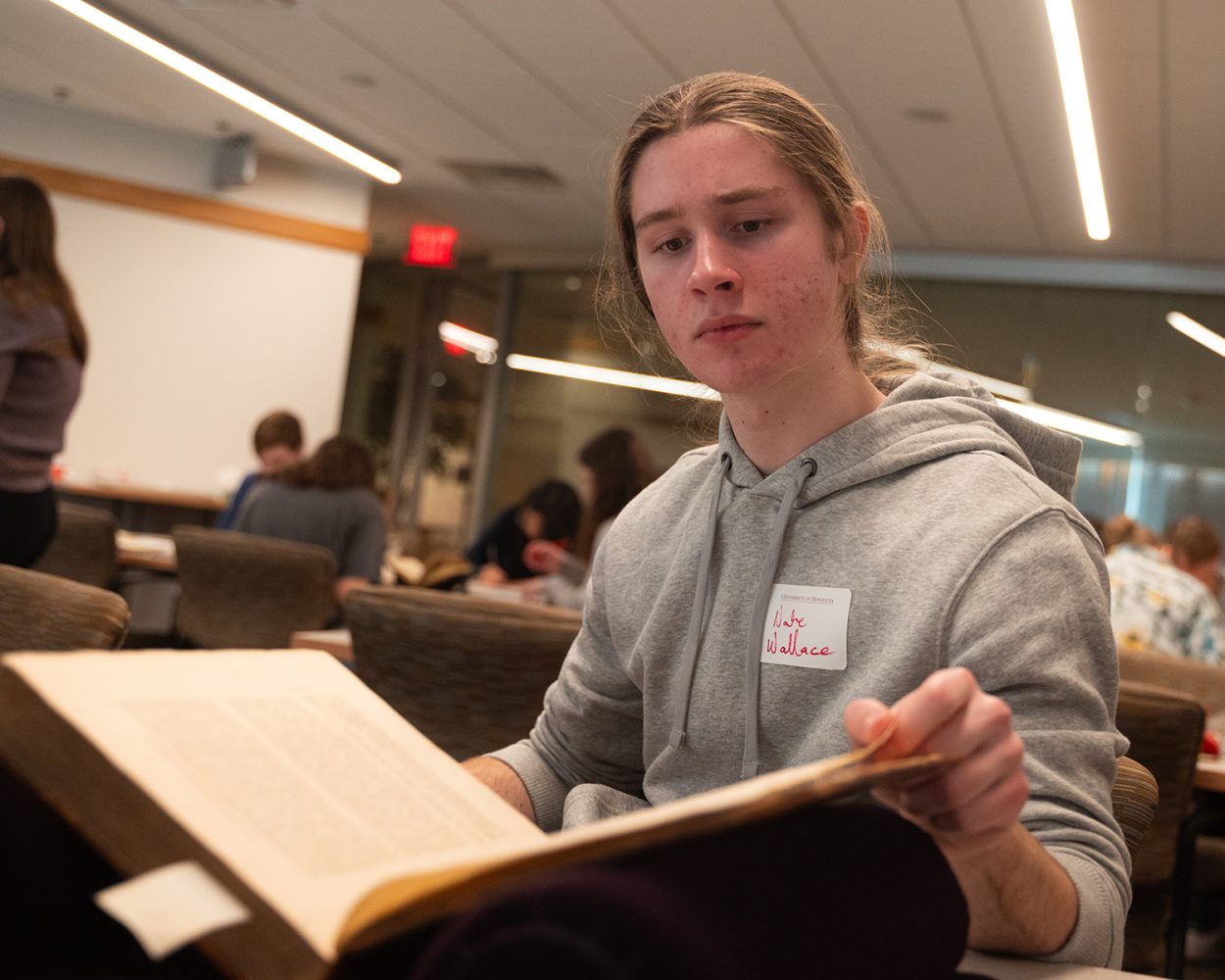

Nate Wallace, a student from Richfield High School, student studies archival materials from the James Ford Bell Library. (Photo/Carl Stover)

Jordan, a student at North Community High School, was one of them.

“I feel like a historian decoding things and trying to figure out what was going on,” he remarked while poring over 17th and 18th century trade materials from the James Ford Bell Library.

“It’s been really interesting,” said Shahnaz, a student from Burnsville Senior High School. “These [materials] are so old. They’re not just photos you take on your phone. They’re here. They’re hand-written, hand-drawn.”

“My hope is that this type of immersive experience will change the way students think about the past, and make history feel more alive,” said Dr. Gerbner. “History can help us answer questions we have about the world today, and the archives are one place we can go to investigate answers to our questions.”

Shahnaz, a student from Burnsville Senior High School, completes a source material activity using resources from the James Ford Bell Library. (Photo/Carl Stover)

Anne Good, Assistant Curator of the James Ford Bell Library, talks to students about archival materials. (Photo/Carl Stover)