My previous post, “The teeth of time,” drew inspiration from one of the brief tangents in Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (London & New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2011). The digression on bookworms allowed Greenblatt to explore the reality of what happened to books produced in Antiquity, and, poetically, to evoke the idea of impermanence and the disintegration of all things. The Swerve is not, of course, about bookworms, but rather, it celebrates the 7,400-line Latin poem De rerum natura (“On the Nature of Things”) by the Roman Epicurean, Lucretius (ca. 99-55 BCE). This poem was rediscovered in a medieval manuscript copy in a German monastery by the Italian humanist, Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459 CE) in 1417. In The Swerve, a book intended for a popular audience, Greenblatt guides readers between Antiquity and the Renaissance; then into the future, as he argues that “On the Nature of Things” had a profound effect on the way that culture shifted during the Renaissance: “This is the story then of how the world swerved in a new direction” (11).

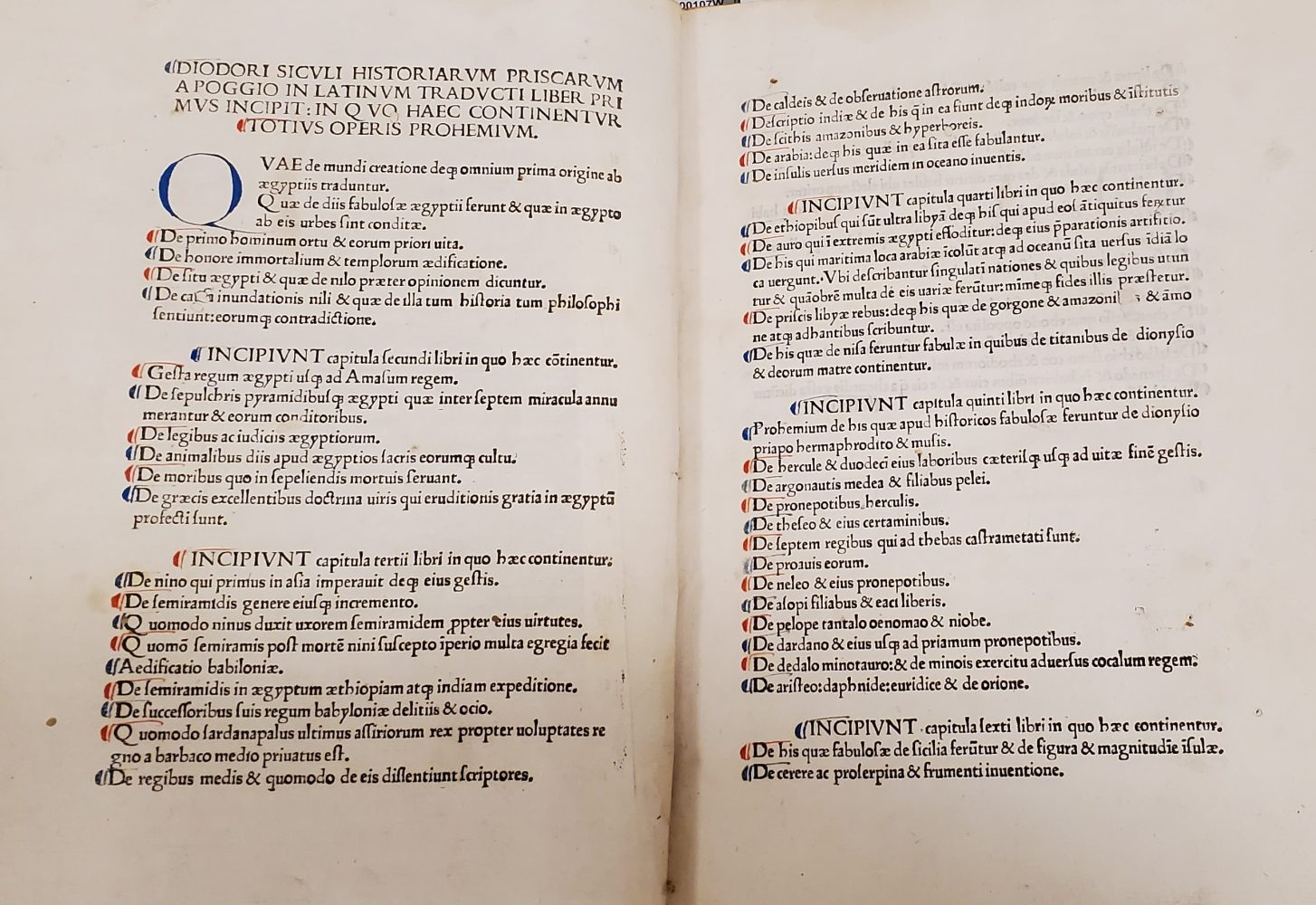

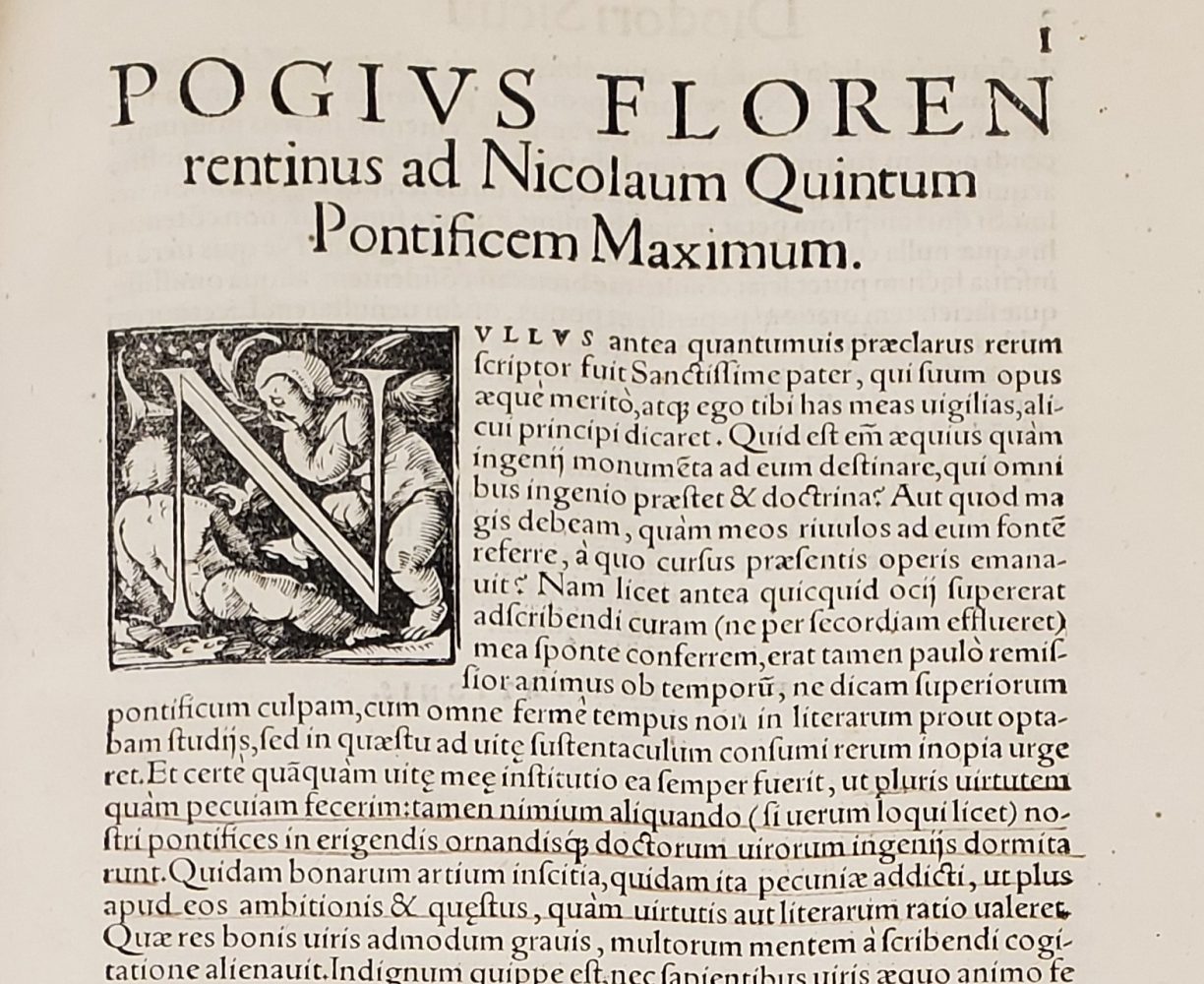

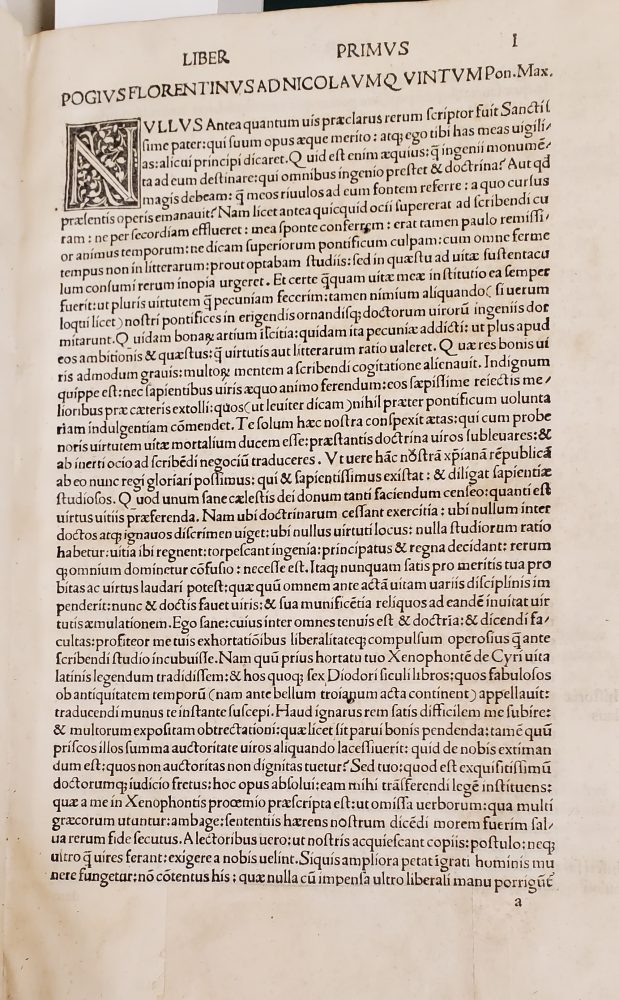

“Pogius Florentinus ad Nicolaum Quintum Pontificem Maximum” – Poggio the Florentine to Nicolas V, Pope. Bell Call # 1559 fDi. This is the first page of a mid-16th century edition of Poggio’s translation of the work of the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus. Poggio had married into a Florentine noble family in 1436 and held the post of Chancellor of that city from 1453 to 1458, the year before he died. Nicolas V was the last pope Poggio served as Apostolic Secretary.

Poggio was an interesting character – most likely from a lower status Florentine family, but well-educated and therefore situated to do well for himself. He was also not an ordained cleric, but nevertheless, became the scribe and secretary who held the closest position to the Pope as the secretarius domesticus or apostolic secretary. The first pope he served, however, was John XXIII, Baldassare Cossa, one of the most corrupt of the Renaissance popes, who, accused of heinous crimes, was forced to abdicate at the Council of Constance in 1414. Though Poggio himself was not touched by the scandal, Greenblatt shows that he was thoroughly capable of playing the games of intrigue and influence typical of Renaissance courts.

Poggio was also a scholar with a deep love of books, and the most sympathetic aspect of his character, particularly for a librarian, is that he was a book hunter. Whenever he was without work (for example, when his pope was deposed) he travelled, searching for the intellectual treasures of the Greek and Roman past. He usually targeted monasteries, since these were the places where books were copied in the Middle Ages. De rerum natura was certainly Poggio’s most significant discovery, but over the course of his life he recovered several other manuscripts, as well as authoring a number of significant works.

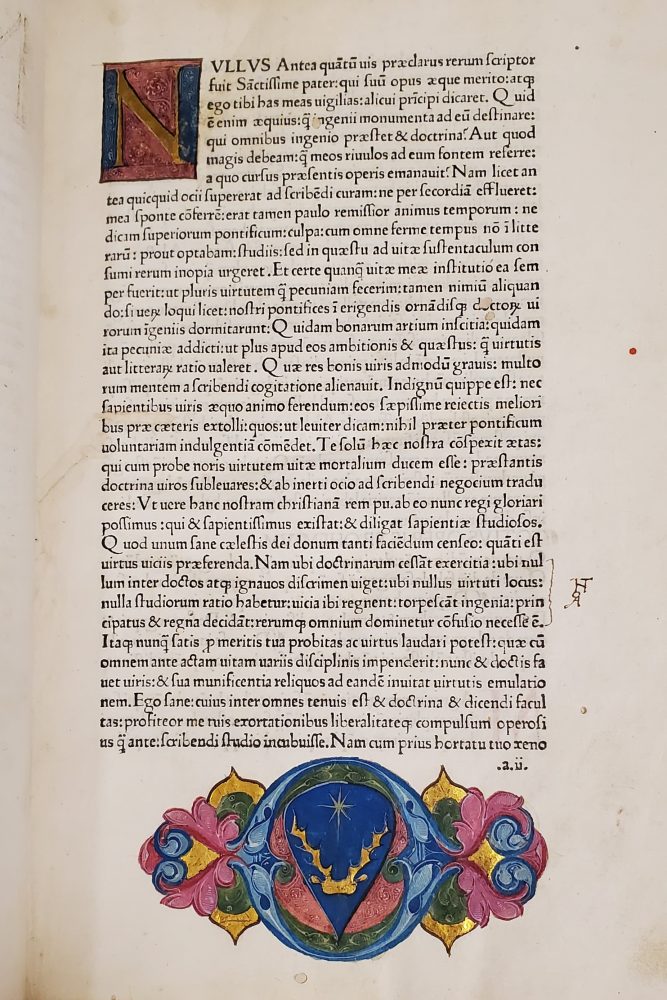

This is the first page of Poggio’s translation of the historical works of Diodorus Siculus. This book is an incunable, one of the earliest printed books. The page was decorated to make it look like a manuscript page. Bibliothecae historicae libri VI, (Venice, 1476). Bell Call # 1476 Di.

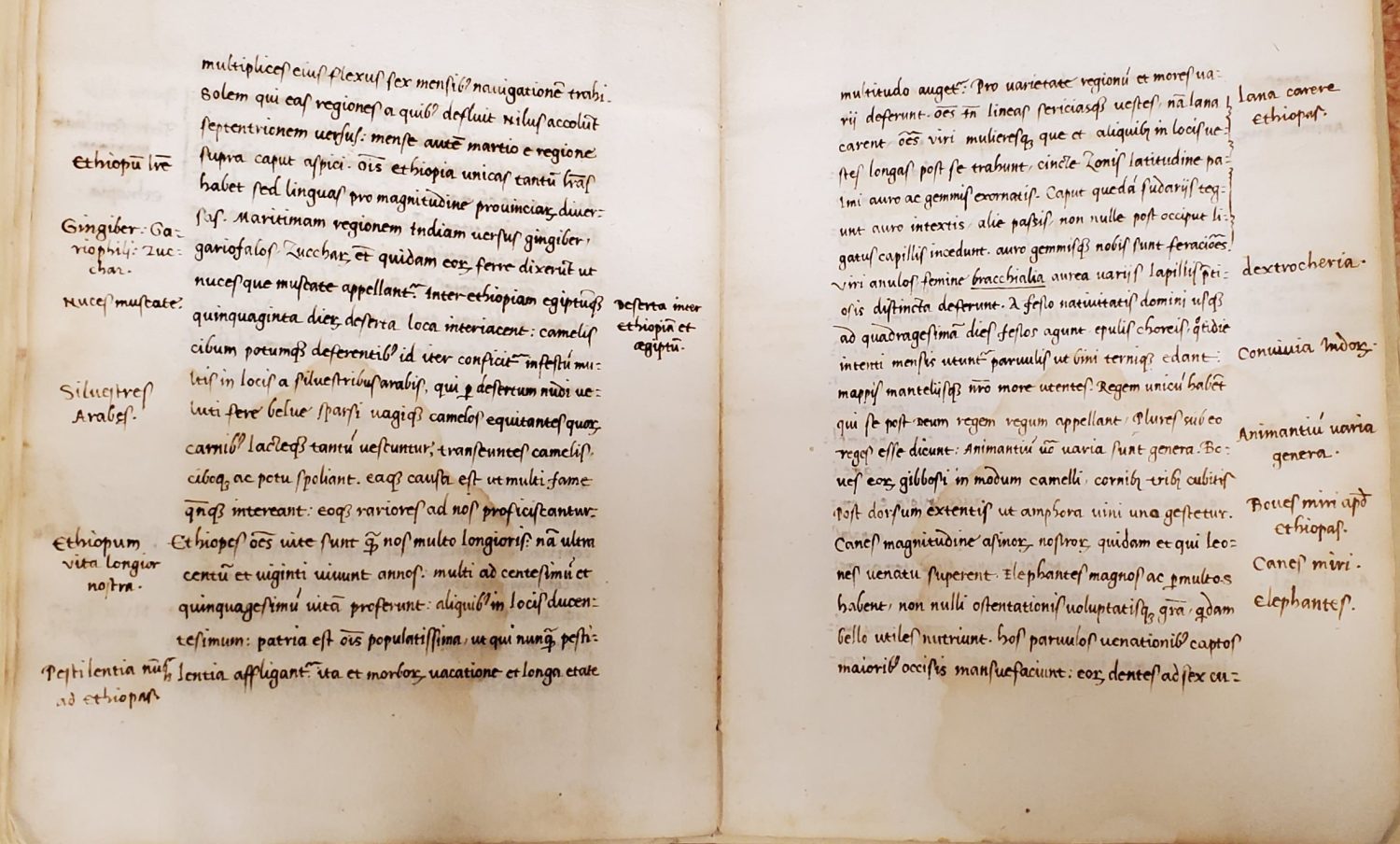

Greenblatt’s book sent me off in search of Lucretian material and traces of Poggio Bracciolini in the Bell Library and the Rare Books collection at the University of Minnesota. The Bell Library does not have a copy of De rerum natura, but it does have several other works by Poggio. The manuscript De varietate fortunae liber IV, ca. 1500 [Book Four of On the Vicissitudes of Fortune] is quite remarkable. The beautiful handwriting made me think, at first, that this was a manuscript written by Poggio himself. However, we are quite certain that it was written after Poggio’s death (1459), and indeed after 1492, because this manuscript mentions discoveries in the New World.

Manuscript copy of Book Four of Poggio Bracciolini’s “On the vicissitudes of fortune,” which includes an account of Nicoló Conti’s journey to the East. De varietate fortunae liber IV, ca. 1500. Bell Call # 1500 Br.

Greenblatt notes that the script developed by Poggio and a few other collaborators was the basis for the typeface we call “Roman”: “perfectly beautiful script, almost magical in its regularity and fineness” (116). Greenblatt argues that the creation of this new, legible script, was emblematic of the larger humanist project, “a project that linked the creation of something new with the search for something ancient” (116).

On the Vicissitudes of Fortune is a moralistic work overall, and the Bell collection only has this manuscript version of Book Four, which is an account of one of the earliest journeys from Europe, through the Middle East, across Iran and India, all the way to Indonesia (mostly over land), by the Venetian adventurer, Nicoló Conti (1395 -1469). Conti recounted his 25 years of travels to Poggio, and this is one of just 31 extant manuscript copies. The person who copied the original manuscript thought that the newly reported Caribbean islands might be connected to the Indonesian archipelago that Conti described, and this is how we know that our manuscript must be dated after 1492.

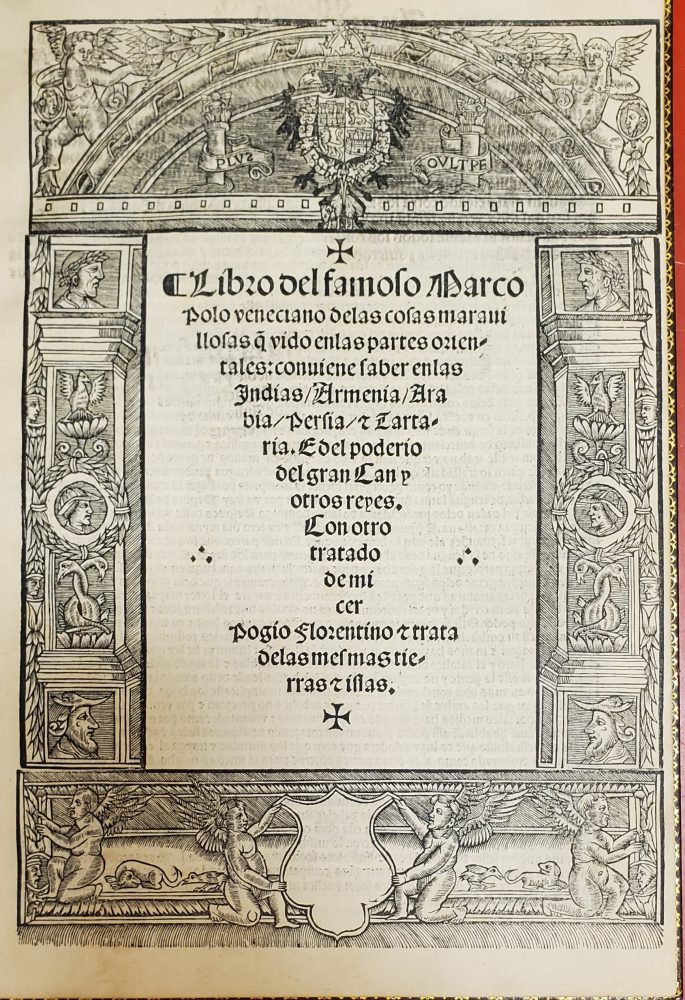

Libro del famoso Marco Polo veneciano de las cosas marauillosas q[ue] vido en las partes orientales (Logroño, 1529). Bell Call # 1529 Po. A Spanish translation of the journeys of Marco Polo, together with Poggio’s recounting of Conti’s travels.

Additionally, the Bell has copies of Poggio’s translations out of Greek of parts of the geographical-historical works of Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE), as well as Poggio’s continuation of Leonardo Bruni’s “History of Florence” [Historie Fiorentine]. All of these are incunabula, or books printed before 1500, using the very new technology of the printing press.

A version from 1496 of Poggio’s translation, from Greek to Latin, of the work of Diodorus Siculus: Bibliothecae historicae libri VI (Venice, 1496). Bell # 1496 fDi.

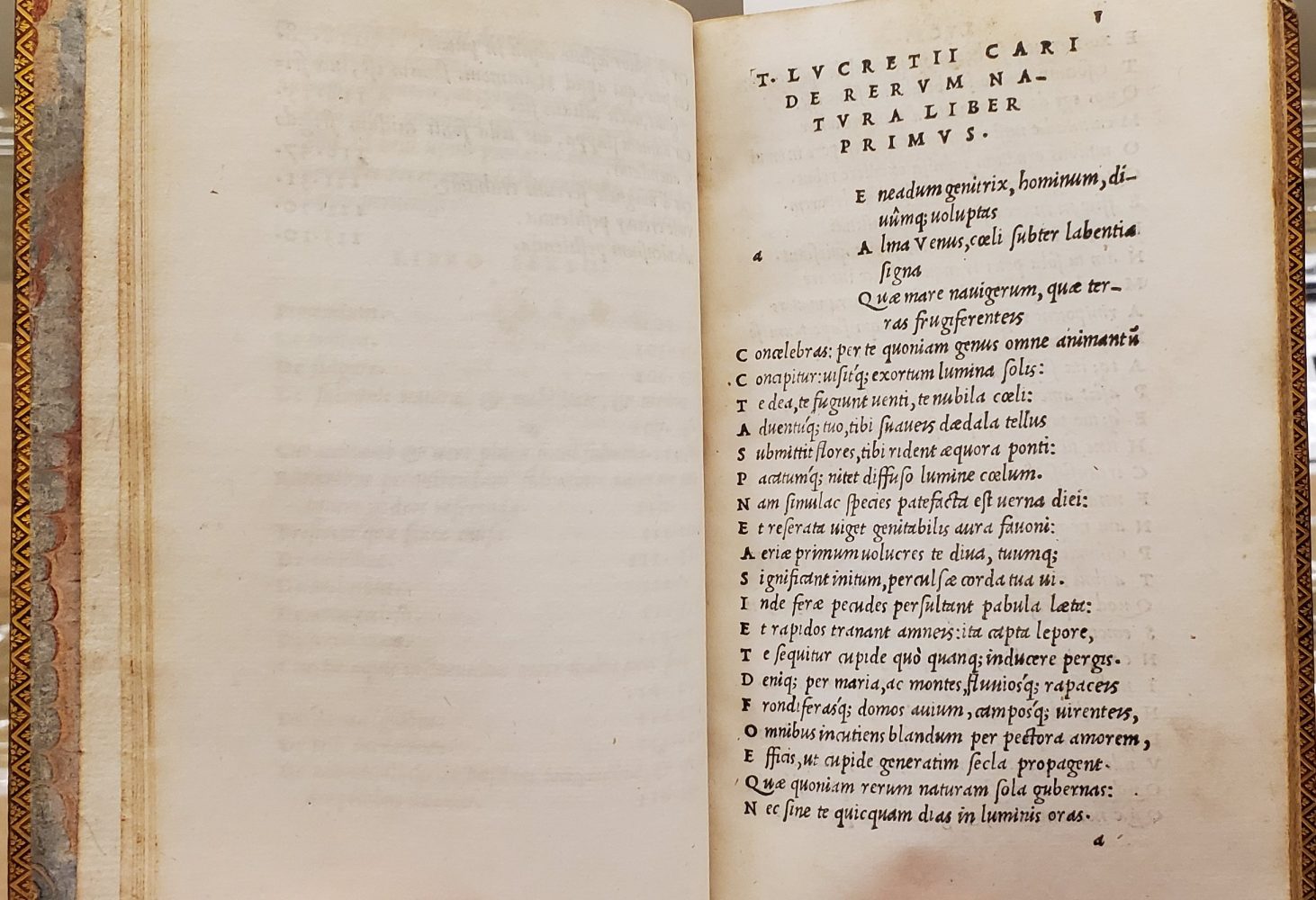

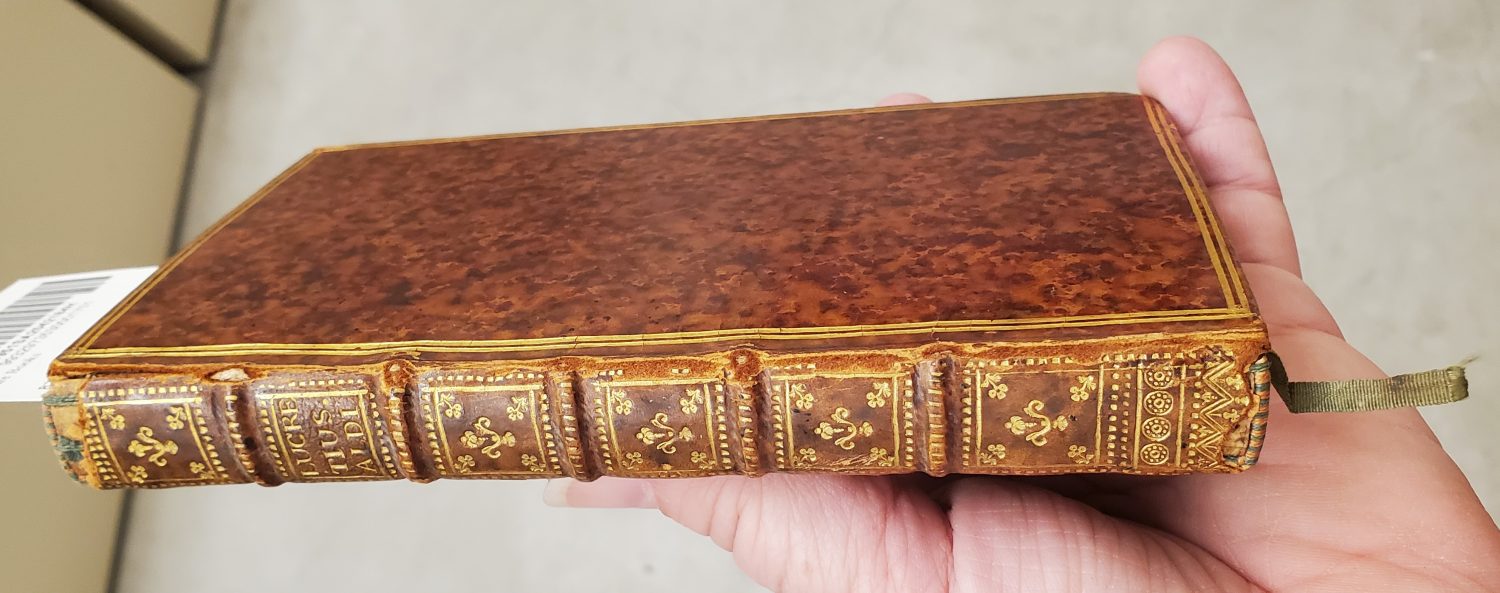

To find editions of De rerum natura, I had to search in the Rare Books collection. Although 50 Renaissance manuscript copies of De rerum natura are extant, unfortunately, none of them is in Minnesota. We do, however, have several of the earliest printings of this work, including that done by Aldus Manutius in 1515, most likely utilizing the copy of the manuscript made by Poggio’s close friend Niccolo Niccoli.

Aldus published small, elegant books for individual readers, and thus helped to start a reading revolution.

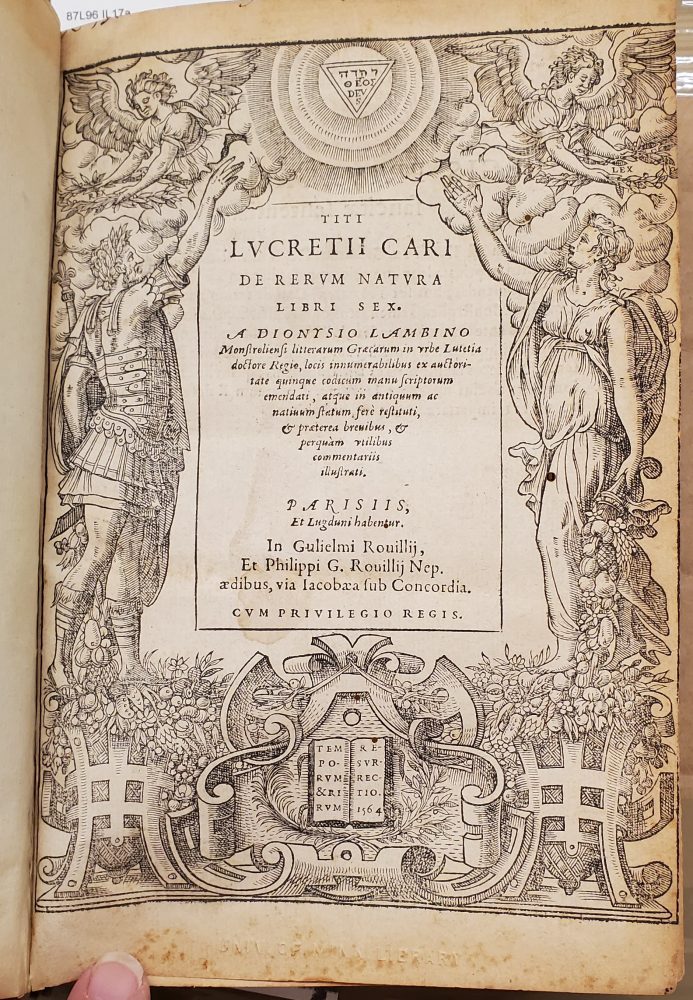

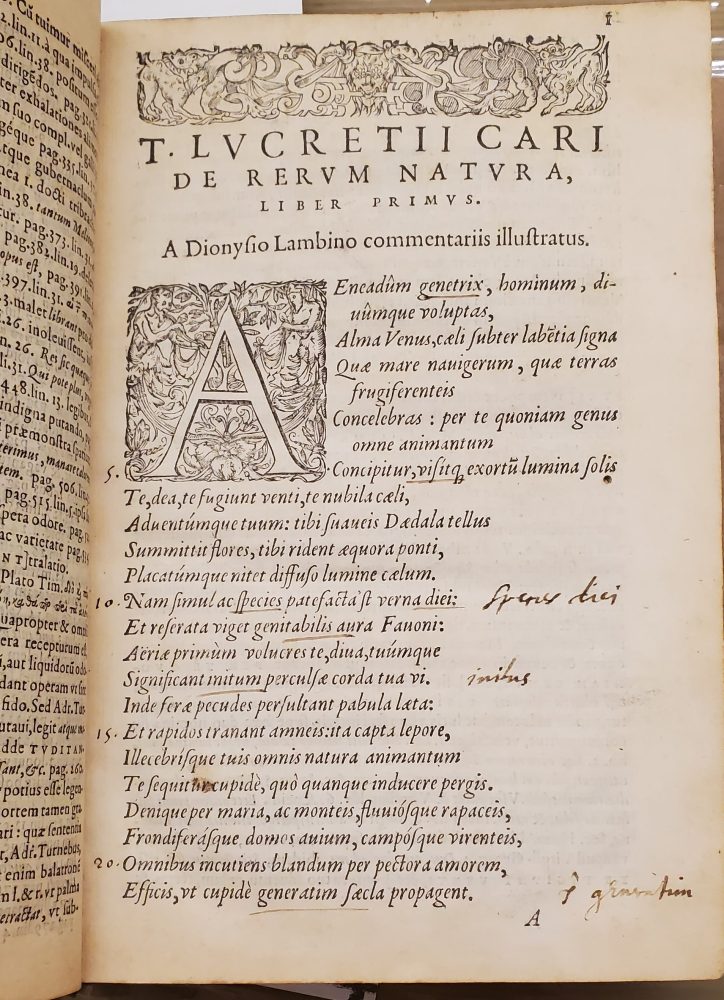

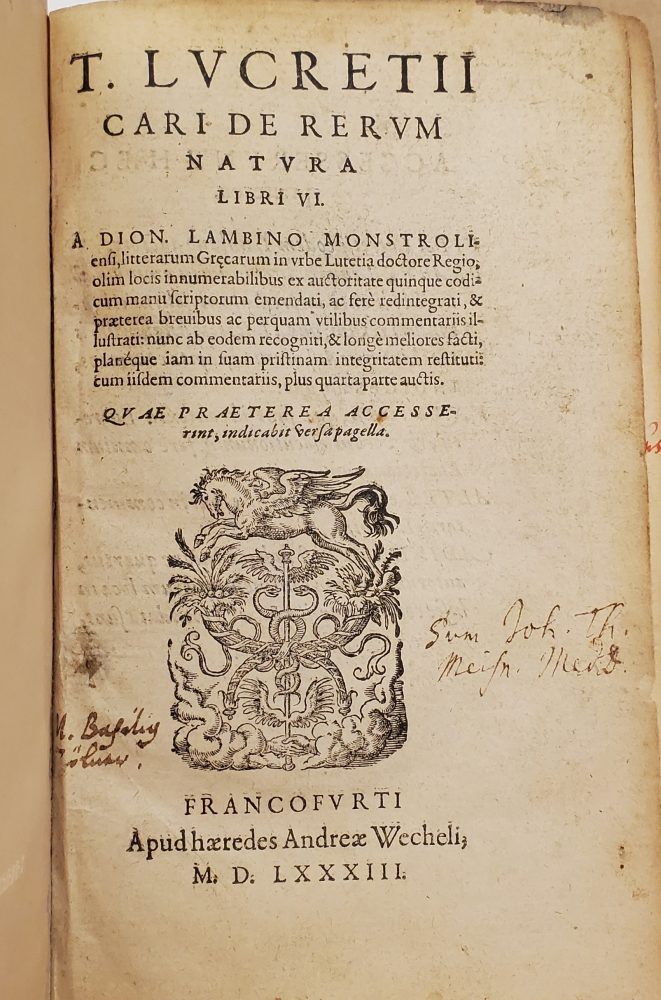

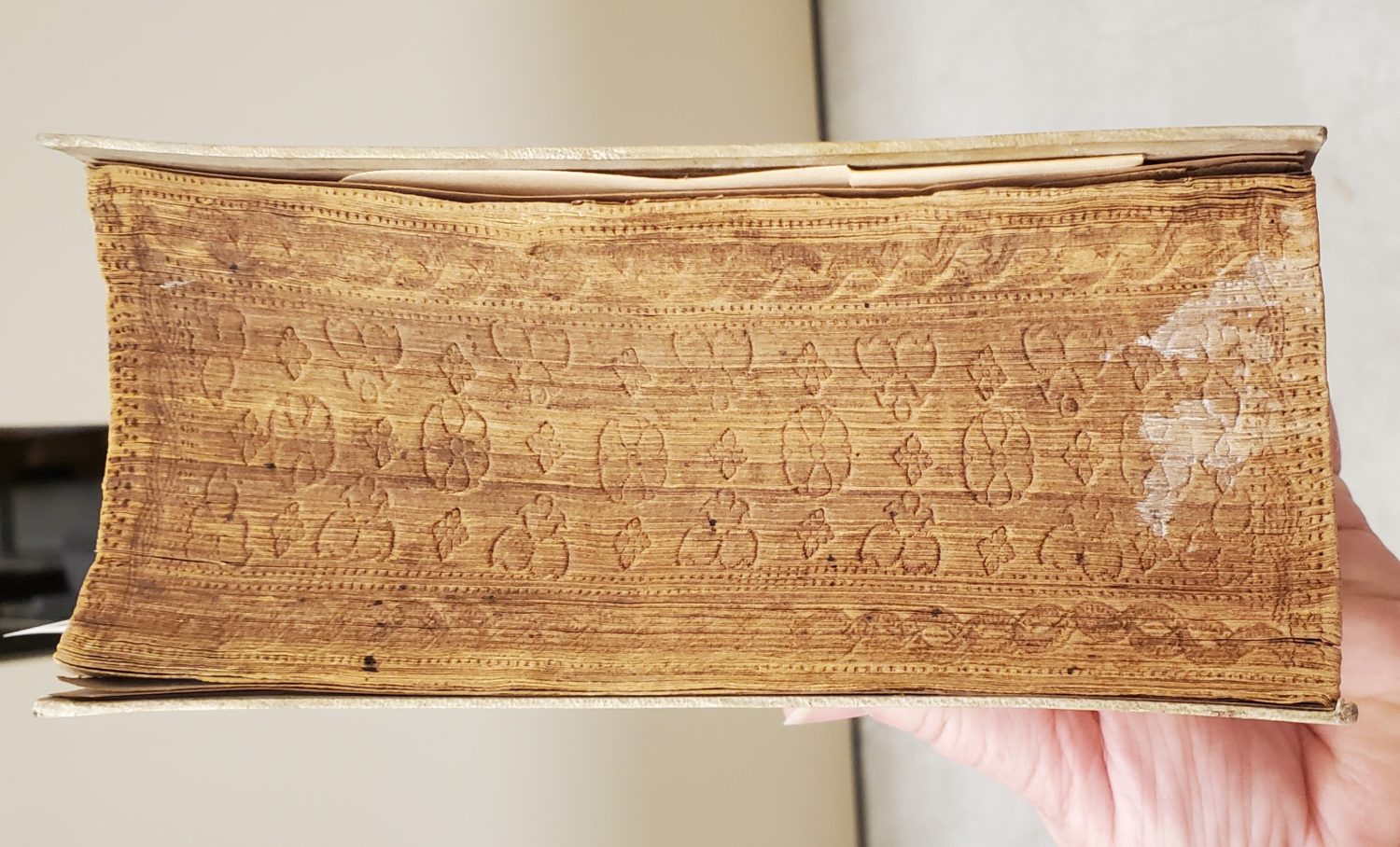

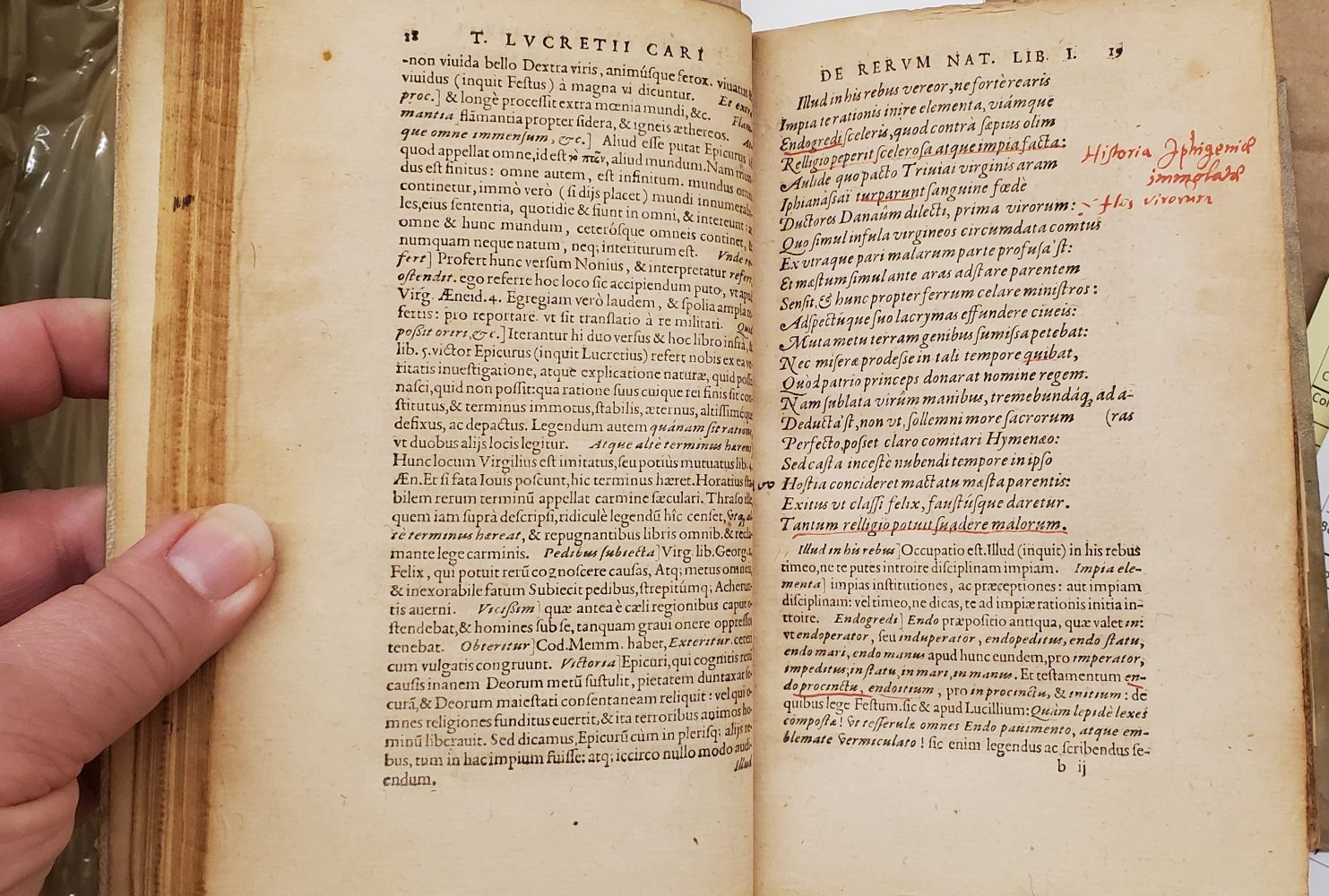

Further copies include two editions by the French classical scholar Dionisius Lambinus (1520-1572) (aka Denys Lambin). Since the poem was so opposite to the prevailing Christian worldview, Lambinus distanced himself from the import of the text, only pointing out its poetic merits. Exemplars in the Rare Books collection include editions from presses in both Paris and Frankfurt. These copies also show how the poem gained more and more commentary over time.

Densely printed poetry and commentary, with reader’s notes in red, in the early Frankfurt edition of De rerum natura.

Lucretius’s poem, as noted earlier, is in the Epicurean tradition and is an exposition of materialist philosophy. Greenblatt argues that the rediscovery of “On the Nature of Things” had a profound influence (the swerve effect) on the whole course of the modern world. Some of the ideas found in the poem include the concept that all things are made up of invisible particles or “atoms” that are constantly in motion, coming apart, and then recombining to make new forms, but at the same time never ending. The “atoms” have no Creator or Mover, and thus human beings are not unique or specially privileged as living beings in the world. Their souls are not immortal, there is no afterlife, and all religion is essentially cruel and delusional. Rather than finding this profoundly depressing, Greenblatt perceives this philosophy as being the basis for freeing human minds, allowing humankind to break confidently into the modern era – creating something new from something ancient. Thus, says Greenblatt, paraphrasing Lucretius, “Life should be organized to serve the pursuit of happiness” (195), and it’s pretty easy to guess the path through history that he follows after this.

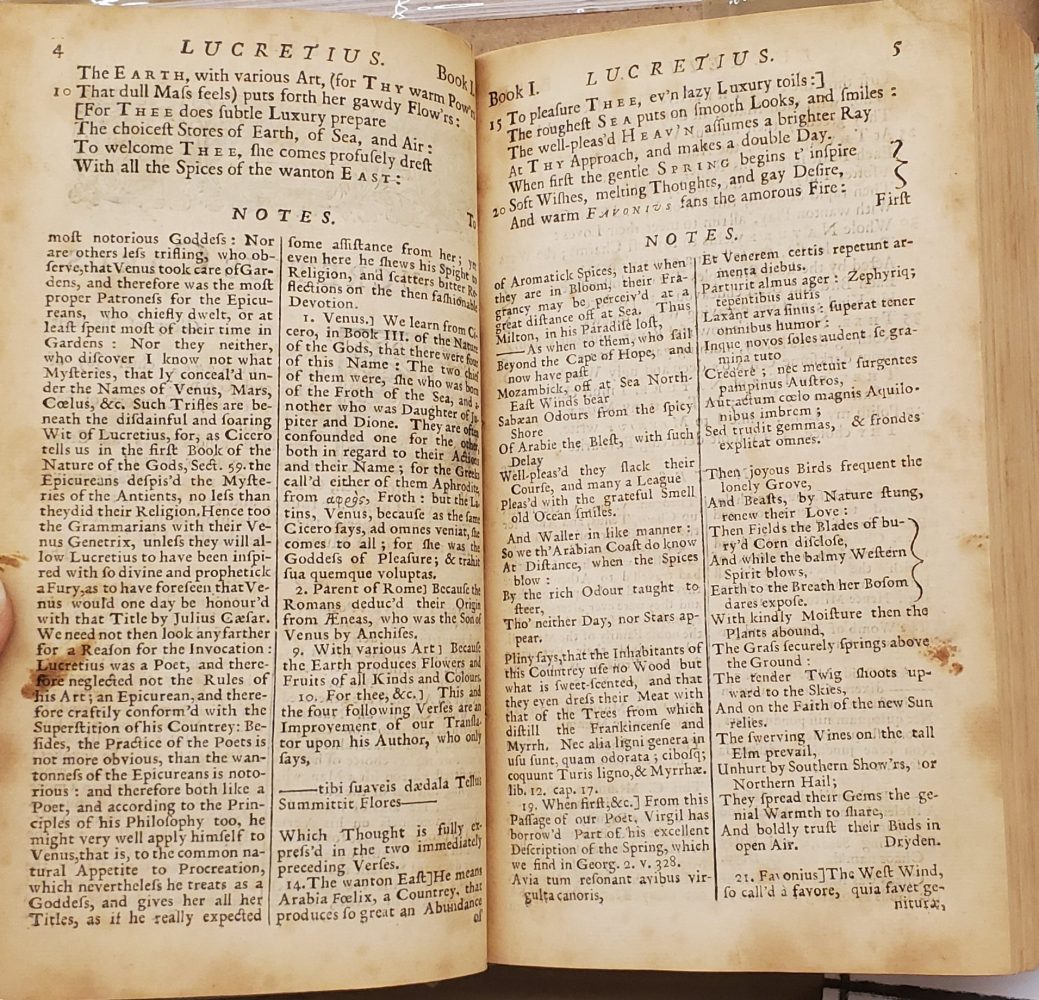

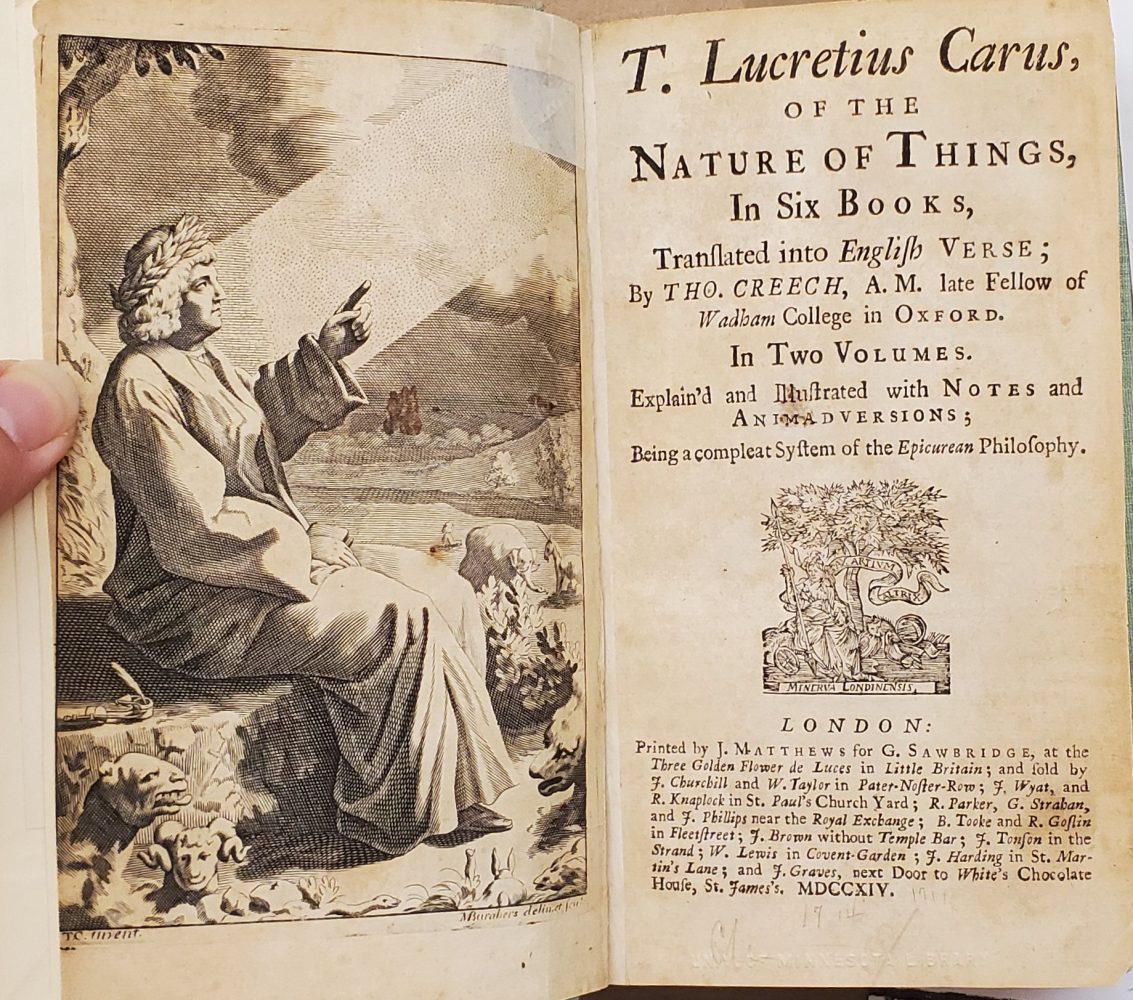

The first published English translation of the whole of De rerum natura was made in 1682 by Thomas Creech (1659-1700), an Anglican cleric, and well-regarded translator of classical works. I have included images from a 1714 edition of this work, which added yet more notes and commentary, mostly likely by a different author, as well as large portions of rewritten verse.

T. Lucretius Carus, Of the nature of things : in six books; 2 vols. (London, 1714). Call # 87L96 JC86a

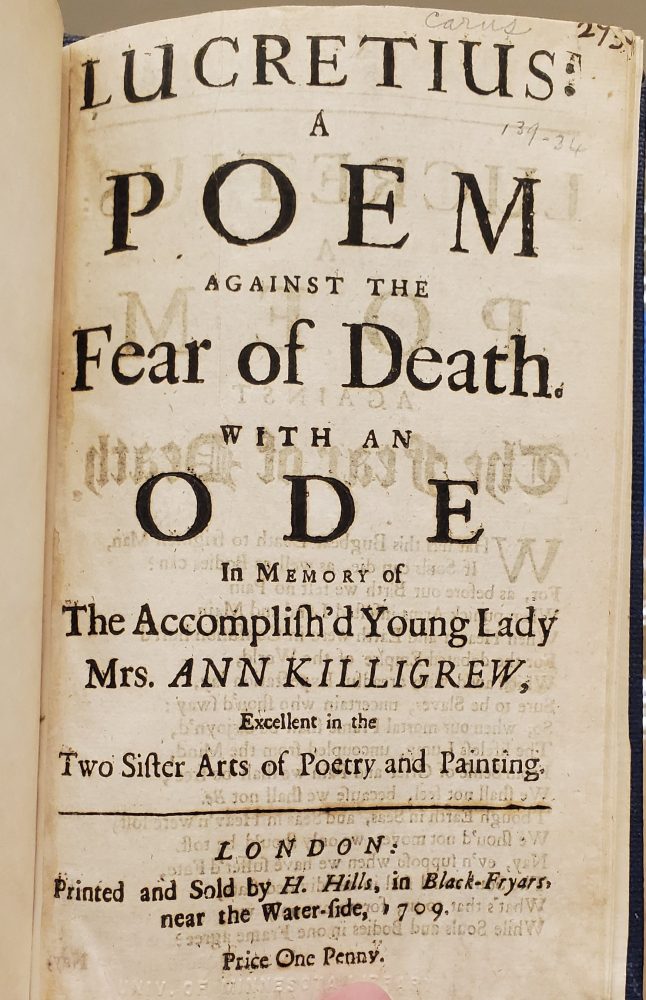

Most often Greenblatt quotes translations by the great English poet John Dryden (1631-1700), who only translated a short portion of De rerum natura to mourn the death by smallpox of a young friend, Anne Killigrew (1660-1685), a promising poet and painter. As is the case with so many of those who we know encountered this poem, we don’t really know what Dryden, a high church Anglican, thought of it. We just know that he, like the others, found the poetry and imagery compellingly beautiful. Greenblatt would add: though books and people pass away, ideas go on.

Lucretius : a poem against the fear of death : with an ode in memory of the accomplish’d young lady Mrs. Ann Killigrew, excellent in the two sister arts of poetry and painting. (London, 1709). Call # 87L96 JD84

I actually disagree with a number of Greenblatt’s historical arguments, and I don’t feel buoyed by his vision of what makes the world modern – but The Swerve is a very interesting book, and I can see why it won the Pulitzer prize.