Underneath the Washington Avenue Bridge, carved into the bluffs of the Mississippi River, are four pale yellow doors. The concrete entrance, nearly four stories high and overrun with ivy and foliage, leads through layers of limestone and shale.

The tunnel is dark and damp. Spiders have made their home around the floodlights and industrial piping overhead. The space eventually opens into the caverns, an archival space 82-feet beneath Andersen Library, and home to over 1.5 million books, manuscripts, artifacts, and more.

- The entrance to the Archives and Special Collections, overrun by ivy and plants, photographed on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

- The tunnel leading into the Archives and Special Collection underneath Andersen Library, photographed on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

The University of Minnesota’s Archives and Special Collections (ASC) alone contributes over 130,000 feet of materials, which when laid end-to-end would almost stretch the distance of a marathon. And amidst the pyramids of cardboard boxes, plywood, and metal shelves, is Micah Janette.

Growing up in Arizona, Janette dreamed of becoming a detective. They would watch the show “History Detectives,” about researchers who investigate the historicity of family heirlooms, historical structures and other artifacts.

“That’s how I learned about archives and what archivists do,” Janette said. “It put together what I liked about problem solving and putting pieces together, all the detective-like work that I was really interested in, and my love of history.”

Processing is a long process

For the past 10 years, Janette has been the head of archival processing at ASC. Before coming to Minneapolis, they worked for the Black Metropolis Research Consortium in Chicago, describing and discovering local Black history.

Janette hasn’t actually processed that many collections in their 16-year career. They focus more on management, keeping the team on-track, the individual collections organized, and the big picture clear and comprehensible.

It’s not as easy as it sounds. Accepting new material into the archives is a lengthy and laborious process. A small collection could be processed in a matter of days, while others could take years or even decades. From start to finish, it takes on average about two years to process new collections, they said.

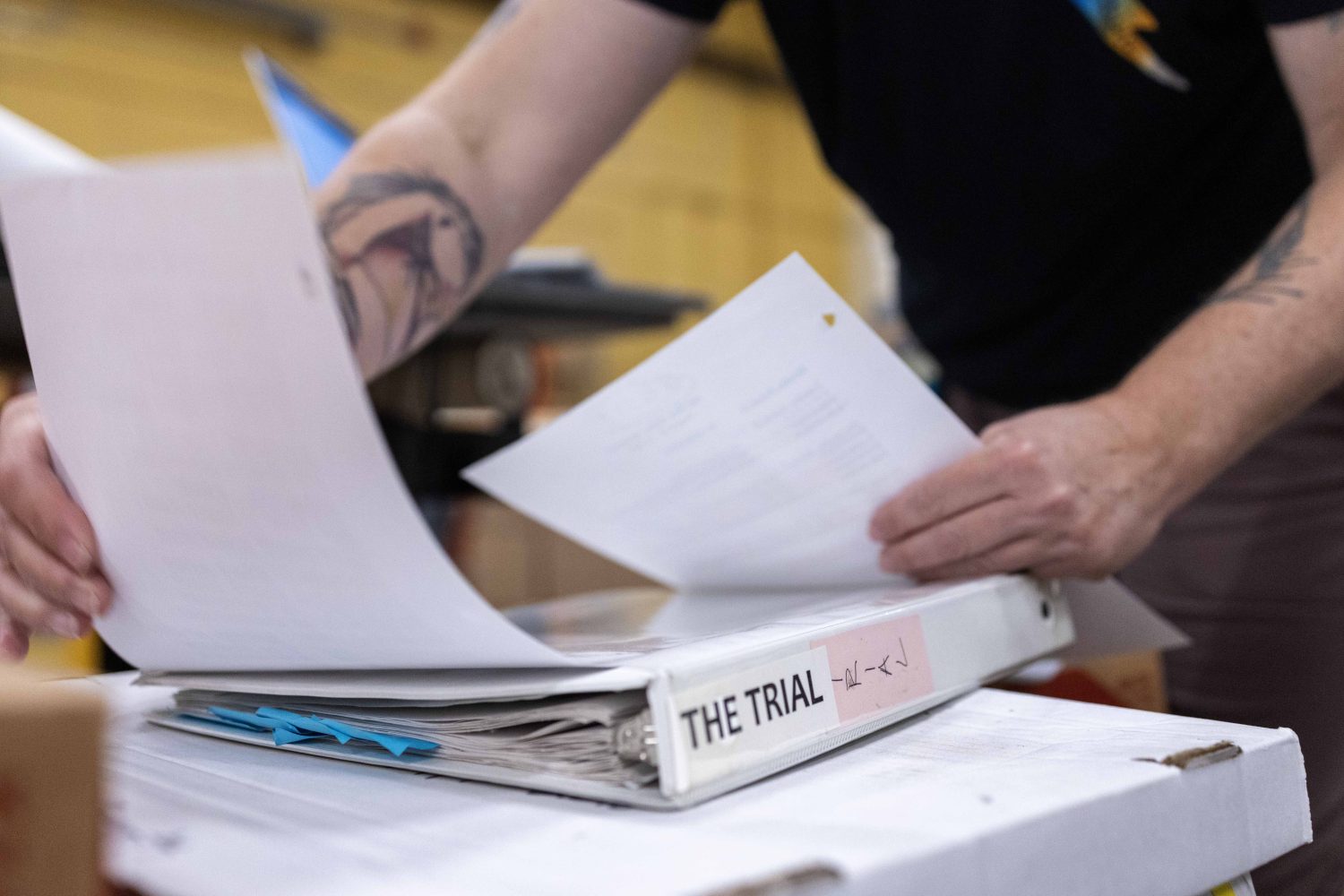

Micah Janette, head of archival processing at the University of Minnesota Libraries, works through the accessioning process of materials for the Performing Arts Archives, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

And the stack of new materials never seems to get any smaller. Around 40 percent of materials haven’t been fully processed yet, Janette estimates, though they are publicly available through collection finding aids, which are published online. It’s a squishy workaround dubbed the “more product, less process” method of making collections accessible with the least amount of effort.

Janette is the only permanently-funded, full-time staff member in Central Processing, and there’s strong pressure to make collections available as soon as possible. But that can come at the expense of giving the collections the time they deserve to adequately describe, highlight, and organize them. Janette estimates that less than a third of materials are not available to the public.

No surprises

Before new materials land in the loading dock, it all starts with a conversation. Archivists and curators spend a long time, sometimes years, talking with potential donors about their materials, the subject area it spans, the amount of boxes, the condition and potential preservation issues, and so on.

“It’s a long process of building that relationship and just mutual understanding that once the creator is done with the material, then there will be a future donation,” Janette said.

Every collection has their own scope of materials, but the most common type in the caverns are personal papers and records of organizations. Organizational records typically include correspondence, financial records, and photographs, while personal papers also include biographical information.

Micah Janette, head of archival processing at the University of Minnesota Libraries, works through the accessioning process of materials for the Performing Arts Archives, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

When possible, before a collection arrives at Andersen Library, staff will visit the potential acquisition on-site to verify the contents and conditions, identify immediate preservation concerns, and avoid “any surprises.” From there, the material is either shipped to the Libraries or moved by staff members.

When there are substantial preservation issues, staff tries to rebox the materials on-site before they come to the loading dock so they’ll arrive in clean boxes, but it depends on staff resources and the timeframe that the materials will arrive.

Before coming to the Archives, materials aren’t usually stored in highly-controlled environments, so Janette expects some preservation issues, mainly from mold or water damage, and pest damage from bugs, mice, squirrels, and chipmunks.

“It’s a nice surprise when things come in, and they don’t have preservation issues,” they said.

If you want to properly preserve your own materials and family records, keep them in a cool, dry place. Janette keeps their records in the basement in archival boxes (plastic boxes are a good alternative) to protect from dust, sunlight, and potential pests. They also store them off the ground, to prevent water damage from mild flooding.

The jack of all archives, master of none

Once new materials finally come to Andersen, Janette begins the “accessioning process,” which is how donations are formally accepted into the archives. This involves reboxing the materials, allowing them to inspect every single item and create an inventory, which gives staff more control and understanding of the collection.

If there are preservation issues like pests or mold, Janette hands the materials off to preservation staff. The sterilization process can be as simple as vacuuming everything. But for complex cleaning, Janette seals the materials tightly in a garbage bag – “It’s very technical,” they joked – and sends it to the Minnesota Historical Society’s conservation department. From there, it’s frozen until any infestation has been killed. Afterwards it’s vacuumed and reboxed.

Micah Janette, head of archival processing at the University of Minnesota Libraries, works through the accessioning process of materials for the Performing Arts Archives, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

Most documents are salvageable. It’s rare for mold to completely eat through materials, or for water damage to turn stacks of paper into a brick of mush and pulp. And if a document is too fragile to be handled, staff will create a digital copy and a high-quality photocopy.

Depending on the size of the collection, it can take four weeks to multiple years to physically rehouse the materials, and longer to create an inventory and finding aid, Janette said. There aren’t staff members who solely work on accessioning, and the stream of new materials exceeds the time and resources available to process them. But if a collection already has an inventory, the process is much faster.

“The hardest part is going through and identifying all of the stuff,” Janette said.

But it’s also their favorite part. They enjoy learning about the collections, reboxing the new files and documents, uncovering the history behind each piece, and understanding why it’s worth preserving.

Micah Janette, head of archival processing at the University of Minnesota Libraries, works through the accessioning process of materials for the Performing Arts Archives, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

“I really love my position because I get to see little bits and pieces of what all of the collections are. So I’m a master of nothing, but I know a lot about a lot of little things,” they said.

Janette remembers working on one donation from the Tretter Collection, a selection of personal papers from a lesbian woman who struggled with addiction and trauma in her family. Usually materials are self-curated by the donor, and emotional items are left out, but this collection was “incredibly raw.”

“I’ve still never come across a collection like this,” Janette said. “It really left an impression on me, partially because there was no attempt to hide the hard stuff.”

The ‘more product, less process’ process

Once accessioning is complete and staff have an overarching idea of what the materials are and how much material exists, they move onto “processing,” or describing the collection in detail.

This starts with a “processing plan” which outlines the high-level points of the collection: it’s title, the timespan of the materials, the total number of boxes, preservation issues that have been solved or will be eventually (non-urgent issues like rusty staples or paperclips, loose newspaper clippings, dirt and cobwebs), and finally a timeline for processing completion.

At this stage, archivists and curators can either publish the finding aid online and provide public access, or move the materials off-site where it won’t be accessible, either because there isn’t an immediate research demand, or because the collection is too complex to provide access before processing is complete.

Micah Janette, head of archival processing at the University of Minnesota Libraries, works through the accessioning process of materials for the Performing Arts Archives, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

Having consistent resources for processing “really makes a difference,” Janette explained. While some collecting units handle accessioning, inventory, and processing internally, other collections don’t have that capacity, which is where Janette comes in. Central processing fills these labor gaps, especially for collections that are larger, high priority, or have many preservation issues.

It’s helpful to have funds to process a specific collection, they said, but it also makes the process complicated. It takes time to hire and train temporary staff whose contract only lasts from a few months to a few years.

“If we don’t have consistent funding coming in, then we’re constantly training,” they said.

“We’re conducting exploitive hiring practices essentially, where we’re constantly depending on underpaid temporary staff.”

Micah Janette, head of archival processing at the University of Minnesota Libraries, works through the accessioning process of materials for the Performing Arts Archives, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

Currently the process heavily leans on student workers. In addition to accessioning, students also inventory the documents, labeling each folder, identifying the box and folder number it belongs to, placing them in archival folders if necessary, adding them to ASC’s content management system ArchivesSpace, and more.

Staff also work in tandem with student workers to review the inventory, organize the collection, create collection outlines, write biographical or historical notes about the individual donor or organization, and write a “scope and content” note, an overview of the collection that eventually becomes the collection guide and finding aid.

Once all these tasks have been completed, the processing process is done, and Janette can finally and permanently move new materials into the caverns.

A great archivist can come from anywhere

Janette would prefer to have dedicated departmental funds to support hiring more full-time staff members, and not necessarily those with a degree in library science or prior experience. There’s an over-reliance on professionalism in the archives, which “does a great disservice to our ability to think more inclusively about how collections are described, used, and who has access to them.”

For example, when Janette processed the Josie Johnson Papers from the Givens Collection, it challenged their perspective as a white archivist, and they had to reconsider which materials are typically considered important and worth preserving.

Johnson is a veteran of the Civil Rights Movement, advocate for fair housing and employment, and the first African-American regent at the University of Minnesota. ASC wouldn’t typically keep credit card statements as part of an archival collection, but in this case, it demonstrated how much Johnson traveled and how much of her personal finances she invested in her advocacy.

- Micah Janette, head of archival processing at the University of Minnesota Libraries, works through the accessioning process of materials for the Performing Arts Archives, on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

- Stacks of cardboard boxes in the loading area of the caverns, photographed on Monday, July 15, 2024, in the Archives and Special Collections. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

“There’s no other financial evidence of the burden and the cost that that type of activism has on the individuals and community,” Janette said. “So just being able to really have to think outside of my lived experiences as a white person.”

Archives have historically been structured for white audiences, and Janette worries about how to change that culture. Removing barriers to accessing the archives, like having more off-campus community engagement, is a first step. But archives should also change their hiring practices and find candidates outside the traditional academic pathway.

“Anybody can do the work that we do,” they said.