By Sommer Wagen

On Mon., Sept. 29, the University Libraries hosted members of the Minnesota Public Health Association (MPHA) and other guests at Andersen Library for a Taste of Public Health Archives in Minnesota, along with a tour of its subterranean caverns that house 93,000 cubic feet of archival material.

Since 1907, MPHA has brought together public health professionals and interested citizens across the state dedicated to creating a healthier Minnesota, according to its website.

The goal of this event, explained MPHA History Committee co-chairs Donna Anderson and Kathleen Norlien, was to make members more aware of its records, which are housed within the University’s Social Welfare History Archives.

MPHA Executive Director Merry Grande said, “This is a first-time event for our public health audience. It was the resource [of the archives], I think, that’s attracting people.”

Social Welfare History Archivist Linnea Anderson speaks to attendees during A Taste of Public Health Archives in Minnesota on Sept. 29, 2025. (Photo/Sommer Wagen)

Grande added that the timing of the event also considered the influx of public health graduate students at the beginning of the school year to show the archives as an academic resource.

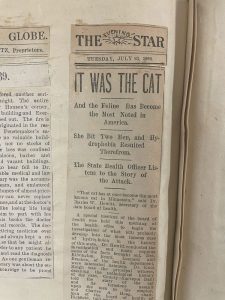

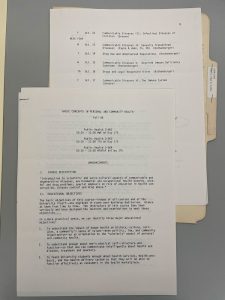

Selected materials from MPHA records were on display alongside artifacts from the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine and the School of Public Health records within the University Archives. An 1889 newspaper clipping declaring “It Was The Cat” that gave two people rabies (or “hydrophobia,” as it was known then) was on view alongside 1950s MPHA conference agendas and the first UMN class syllabus to include AIDS from 1986.

- Archival newspaper clipping from 1889. (Photo/Sommer Wagen)

- Syllabus for Basic Concepts in Personal and Community Health, taught at the UMN in 1986. (Photo/Sommer Wagen)

- Mid-century sign used to designate houses infected with contagious diseases. (Photo/Sommer Wagen)

Anderson said she hoped the combined showcase of the three archives would “spawn some interest and some things that we can discover and follow up on as lovers of history and public health work.”

Indeed, the archival materials prompted discussions of our current times. Emily Beck, assistant curator of the Wangensteen, compared the social effects of bright yellow mid-century signs used to designate houses infected with contagious diseases with masks worn by people recovering from COVID-19.

“History guides why you’re doing a project today,” Anderson said.

The event also helped promote the Archives and Special Collections’ mission to collect historical documents, care for them, and make them available to the public.

Around 15 guests at the event, led by Social Welfare History Archivist Linnea Anderson, crowded into a normally off-limits elevator that took them eight stories underground to where University archives are stored. A noticeable chill blasts onto you upon entering, thanks to the climate control system created to preserve the archival materials. A viewing window looks out onto the striated river bluff limestone shell encasing the facility. The smell of rock and old paper permeates the two-football-field-long space.

Attendees explore the caverns under Elmer L. Andersen Library during A Taste of Public Health Archives in Minnesota on Sept. 29, 2025. (Photo/Sommer Wagen)

Residing in the caverns are shelves towering 23 feet high, filled with boxes upon boxes of archival material, from professors’ papers to children’s books. Even more materials sit in boxes on rolling carts and in flat files lined up against the walls.

“Wasted space is not our friend,” Linnea joked. Guests raved about how exciting it was to get to see where history is stored, and there were no shortage of questions as the tour progressed.

Linnea spoke to the many things the archives offer. They provide an engaging way to learn at both the undergraduate and graduate levels and promote education for everyone. They provide records of real people’s lives and communities like MPHA, as well as a way to learn about the past firsthand.

Norlien added that, as a visual learner, being able to look at and handle artifacts directly helped her more fully understand how things were done in the past.

Grande pointed out the collaborative potential of the archives to bring people together across a range of interests.

“There are lots of different directions that people get pulled in. If you’re interested in research, you not only have the archives, you have other people that may be interested in that topic, too,” she said.

Crucially, Linnea also highlighted how the archives dispel the idea of history as being made up of isolated events by directly showing how present innovation and dysfunction alike were created. She particularly emphasized the timeliness of public health and social work history, particularly in the age of COVID-19.

“History isn’t just sitting there back in the past. It’s happening now.”

And while the caverns aren’t open to the public, Archives and Special Collections is a resource that’s available to everyone.

“I can’t tell you how often, as I’m driving to work or streaming the news, that I think ‘Oh we have something about that. And that, too. That’s documented in the archives,’” Linnea said. “History isn’t just sitting there back in the past. It’s happening now.”

About Sommer Wagen

Sommer Wagen is a freelance journalist based in the Twin Cities, the traditional and contemporary lands of the Dakota and Ojibwe peoples. They graduated from the University of Minnesota in spring 2025 with their bachelor’s degree in journalism.

Sommer Wagen is a freelance journalist based in the Twin Cities, the traditional and contemporary lands of the Dakota and Ojibwe peoples. They graduated from the University of Minnesota in spring 2025 with their bachelor’s degree in journalism.