Louise A. Merriam

Archivist, YMCA of Greater New York

In the 19th century, the CEO of the New York City YMCA, then called a secretary, spent many hours answering the mail. Robert R. McBurney, the “first paid secretary” of the YMCA, was a prolific letter writer. His correspondence and other letters in the collections at the Kautz Family YMCA archives reveal a long-vanished aspect of the “Y.”

The letters show that the YMCA was a social welfare agency in the middle years of the 19th century. It located missing persons, offered advice and assistance on a wide range of topics, and took seriously the many requests to call on or invite a particular young man into the welcoming rooms of the YMCA.

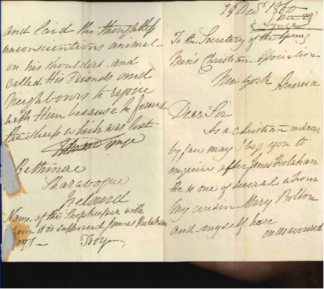

The letters show that people viewed the YMCA as a source of trusted information. The blue letter, from a Philadelphia man in 1864, described a letter he had received asking for money because of the writer’s dire situation. The letter writer, one William Sharpe, wanted to know whether the cry for help was genuine. Another letter, from a man in Portland, Maine in 1865, asked whether an advertised patent medicine cure for masturbation really worked (see below).

The 1860 letter, from a worried relative in East Syracuse, New York, asked the YMCA to find out whether a cousin had been associating with Catholics, reflecting a common fear among the Protestant majority.

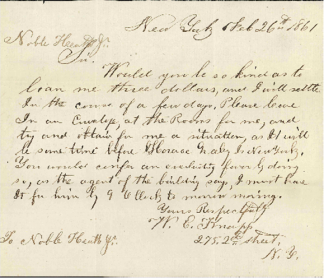

One 1860 New York City letter writer asked the YMCA to loan him some money (see below). He further asked for help getting a job, implying that only then would he be able to repay the loan.

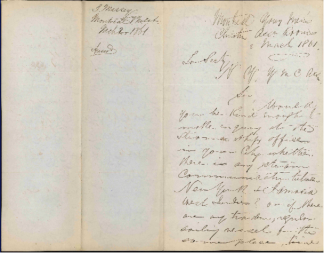

A letter written from Montreal in 1861, sought information about the schedules and fares of steamship lines traveling to Jamaica (see below). The writer added that if there were no steamships, a sailing ship would also be acceptable.

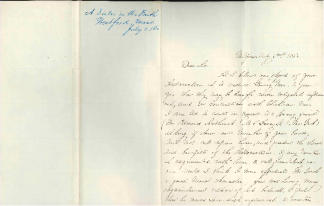

Letter from Jefferson City, Missouri in 1866, begging the YMCA to call upon a young man new to the city to “counterbalance the basest temptations of city life.”

This letter, from Jefferson City, Missouri in 1866, begged the YMCA to call upon a young man new to the city to “counterbalance the basest temptations of city life.” The writer did not want the young man to know about the request, and the signature is “A Sister in the Faith.”

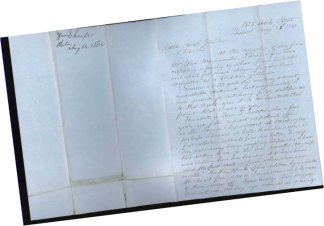

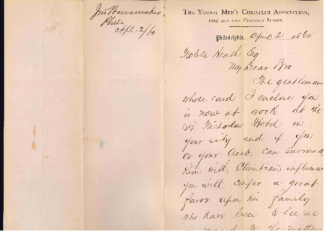

Some of the letters were from well-known people. An 1860 letter from John Wanamaker, founder of the famed Philadelphia department store, asked the New York “Y” to call upon a young man and “surround him with Christian influences.” Like the previous letter writer, Mr. Wanamaker preferred to be anonymous. “Of course, you will not let it be known that his family or our association has been instrumental in placing him under your fatherly care.”

Letter from John Wanamaker, founder of the famed Philadelphia department store, asking the New York Y to call upon a young man and “surround him with Christian influences.”

These letters are just the tip of the iceberg. Annual reports from the period summarize the many hundreds of letters received and the actions taken. Among these actions were tracking down a relative who gave a false name; advertising in the New York papers about the death of a member so that his family would know he had a Christian burial; and finding a young man through his resemblance to his sister. The reports also excerpted letters of thanks, which served as a 19th century version of Google reviews.

In those years, the YMCA in New York City was much more than a gym or a safe, inexpensive place to stay. It offered sanctuary from the perils of the big city. Providing these services required the YMCA to minister to the whole person as well as to his family and friends, providing assistance with matters that today are the responsibility of social workers, teachers, doctors, police agencies and librarians. The actions of the YMCA in response to letters now in the collection show an organization with a very broad mission indeed.

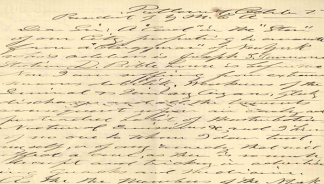

From a man in Portland, Maine in 1865, asking whether an advertised patent medicine cure for masturbation really worked.

This post is an adaptation of a presentation given at Anderson Library’s First Friday series on November 4, 2016.