By Allison Campbell-Jensen

Old books attract John-Ivan Palmer, for the poetry and prose inside, and for traces left by time and previous readers, from notes in the margins to the scent and feel of 100-year-old paper and bindings.

Sometimes books contain surprises. Like that copy of “Seven Storey Mountain” he bought at a library book sale: He wasn’t sure if he would enjoy reading it but he did, keeping with the autobiography of American mystic Thomas Merton until the end. As he turned the last page, a $100 bill fell out of the book: a bonus!

Also a talented writer, Palmer (also known as John-Ivan Pyle) has unexpected gifts for the readers of his latest book, “Master of Deception: A son searches for his father in the house of illusion.” (Available as an e-book for the University community, via the Libraries.)

His nearly school-free vagaries of life on the road as a “show-business kid,” reveal a few tricks — for instance, how the author learned to write with his right and left hands, backwards and forwards, at the same time. And so much more: This compelling memoir has appeal far beyond those who are fans of magic.

Settled in the Twin Cities

Now living in Minneapolis’s Tangletown neighborhood, Palmer and his wife’s home faces the sidewalk atop a rocky bluff face seemingly lifted from the St. Croix River Valley. The creation reflects his life-long love of rocks and geology — another field in which he’s gained expertise despite never finishing high school, nor any of the three universities he attended.

Joel Van Valin, editor of the Minneapolis-based literary journal Whistling Shade, has published many of Palmer’s pieces. The works include essays about how — without microphones — Greek orators and 19th-century speakers made themselves heard by hundreds or thousands of people; the scams perpetrated by people who claim to live off only air; and first-person reportage on the dangers of Guatemala in the 1990s. Palmer also has been honored with a Pushcart Prize for fiction, and has been published internationally.

Palmer’s connection to the Libraries

As a writer and researcher, Palmer has long been a member of the Friends of the University of Minnesota Libraries, so he could have access and borrowing privileges to the University collections. He has used these materials in numerous writing projects, both fiction and non-fiction.

The Archives and Special Collections in the Elmer L. Andersen Library, he says, have “been a fruitful source of arcane information, such as details on 1950s trailer hitches or WWI Croatian draft dodgers (for my memoir, ‘Master of Deception’), works by Ronald Firbank and William Ellory Leonard for my novel ‘Motels of Burning Madness,’ and the training techniques of Greek and Roman orators for an article on the unamplified voice.”

Van Valin says: “He writes about the darker aspects of the mind,” such as the lives of male strippers (at the height of Chippendales’ popularity), and views “backstage” of massage parlors. Palmer grew up differently than most, Van Valin adds. “His people were kind of rovers,” he says. “They traveled for a living.” The nomadic lifestyle stalled for a time in New Brighton, when Palmer was a young teen and his family had their own house — of a sort and for a while.

Under the lights

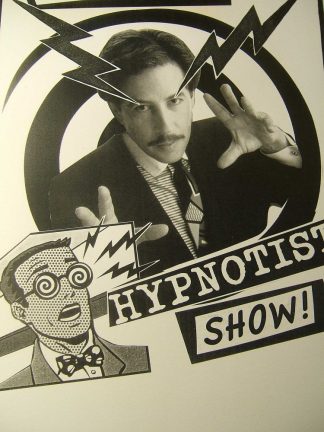

Palmer depicts in “Master of Deception” how he came to take up his father’s field — albeit as a solo operator, with no lovely assistant, nor any rabbits.

“The work he does, he travels light,” says friend Jerry Martin, who for his own magic act mastered juggling.

Palmer hypnotizes small groups of people, performs feats of memorization, and sometimes mesmerizes folks. “When I can get susceptible subjects on stage,” Palmer says, “it is the nature of consciousness that it can be manipulated to an absurd degree.”

His performances are outlined on comedypro.com: “Surprises happen quickly when John-Ivan Palmer takes control of the program. Before you know it you are in the twilight world of mental enigmas all performed through scientific means — power of suggestion, misdirection, close observation, disguised influence.”

He is disarming on stage and charming in person.

“He’s a classy guy,” Martin says. In conversation, he might seem reserved. “But he’s always listening,” Martin adds. “He’s the quiet person who has been tracking every second.”

Though his bookings for comedic mass hypnosis sank for a time during the worst of the pandemic, and the audience for live entertainment was undercut by television decades ago, Pyle has created a career as a hypnotist, a “mind reader,” and a talented writer of creative nonfiction.

‘A born archivist’

“It is a very generous gift because it gives latitude to Kris Kiesling (head of Archives and Special Collections) and other curators to think creatively about how they might support the mission of the ASC and that of the University of Minnesota Libraries.”

—Tim Johnson on John-Ivan Palmer’s bequest

Palmer also has designated his papers, posters, and photographs to be donated to the University’s Archives and Special Collections. “Since fate has placed the U of M and myself in close proximity,” he says, “it is only natural I should be a part of that symbiotic population of self-taught loners and autodidacts who have always coexisted with universities.

“Because I have enriched myself intellectually by what the University [of Minnesota] has provided outside its academic departments,” he adds, “I feel that in the end I owe back the product of that enrichment.”

Palmer is “a born archivist,” says Timothy Johnson, Curator of Rare Books at the U of M Libraries who has visited Palmer in his well-organized den. “The way he thinks about how he keeps his materials and what he decides to keep” are spot-on: He not only has copies of every contract he signed, for example, but also post-show evaluations he collected about every show that he created himself.

Palmer in his planned giving to the U of M Libraries has a twist that is unusual in Johnson’s 40+ years at the Libraries: His planned bequest includes support for his collections and also for the entire Archives and Special Collections. “It is a very generous gift,” Johnson adds, “because it gives latitude to Kris Kiesling (head of ASC) and other curators to think creatively about how they might support the mission of the ASC and that of the U of Minnesota Libraries.”

Johnson says: “He has struck a beautiful balance between the two.”

A room of his own

“Oh, so now he has an actual home,” says Van Valin during the interview about Palmer. Before Van Valin had children, he used to meet Palmer in coffee shops for conversation. “Oh, good.”

It is good. Palmer’s downstairs office — lined with bookshelves loaded with poetry, prose, philosophy, and history — seems a snug nook for deep thoughts. The shelves continue into the hallway. What does he learn from some of these tomes?

“The Romans?” Palmer says. “They pulled no punches. It was amazing what they got away with, as organizers of mass culture.

“They ripped off the Greeks anytime they could,” he adds, “at the same time as they thought they were elitist and effeminate.”

The understanding Palmer has gained of hypnotic controls of crowds — of getting people to do things they wouldn’t otherwise — informs his next book. From terrorists’ recruitment of ordinary people, to those who fall prey to Internet-fostered conspiracy theories, Palmer will go into the “mind control” techniques that began with Anton Mesmer. Much of this research, he says, was done at the U of M Libraries.

In an excerpt from his upcoming book, Palmer writes: “During the reign of King Louis XVI, it was all there: the broadcast, the set, the reception. Anton Mesmer’s proto-television was called a baquet (‘bucket’).

“As you touched the protruding metal rods (rabbit ears) of the baquet (acting as the set), waves of ‘magnetic fluid’ broadcast themselves into your head. The brain-buzz would set you laughing or massage you into lethargy, or just as likely drop you to the floor in convulsions.

“Reactions from Mesmer’s studio audience were so novel and extreme, with all the fainting and shaking and howling, that by 1784 King Louis XVI ordered a commission to investigate. The King’s commissioners questioned the magnetic fluid’s potential effects.

“Mesmer was eventually discredited and run out of town just before they wheeled in the guillotine, but it didn’t cut off the power of his baquet.” And that baquet of powerful staged influence continues to be summoned today, by Palmer, pundits, and politicians.

In the future, because of his bequest, Palmer’s drafts, papers, correspondence, and more will be accessible to the public through the U of M Libraries.

He writes: “Organized collections of one-of-a-kind documents will, sooner or later, be of great interest to a researcher seeking details on forms of life such as mine outside the usual boundaries.”

He trusts that the curators will handle them well — when that time comes.