Some of Minnesota’s richest farmland lies in Blue Earth County, and the white settlers of Mankato wanted it. There was just one problem. The Ho-Chunk people already lived there.

The year was 1863, just shy of the U.S.-Dakota War, and although the Ho-Chunk Nation remained neutral, it gave settlers the perfect excuse.

To execute their plan, they formed the Knights of the Forest, a secret society with one goal: “To banish forever from our beautiful State every Indian who now desecrates our soil.” What followed was one of the most grisly forced removals in the nation’s history.

Cathy Coats, a metadata specialist at the University of Minnesota Libraries, has spent the last 10 years researching this genocide. Her book “To Banish Forever: A Secret Society, the Ho-Chunk, and Ethnic Cleansing in Minnesota,” recently published by the Minnesota Historical Society, documents this history, but Coats hopes this work is just the start.

“This book is really meant to be about justice work for Ho-Chunk people,” Coats said. “There’s a lot of Ho-Chunk people living in Minnesota, hundreds of Ho-Chunk people living in Minnesota, and they’ve always lived here. They have trust lands in Minnesota. They’re part of the state.”

‘There are many Trails of Tears’

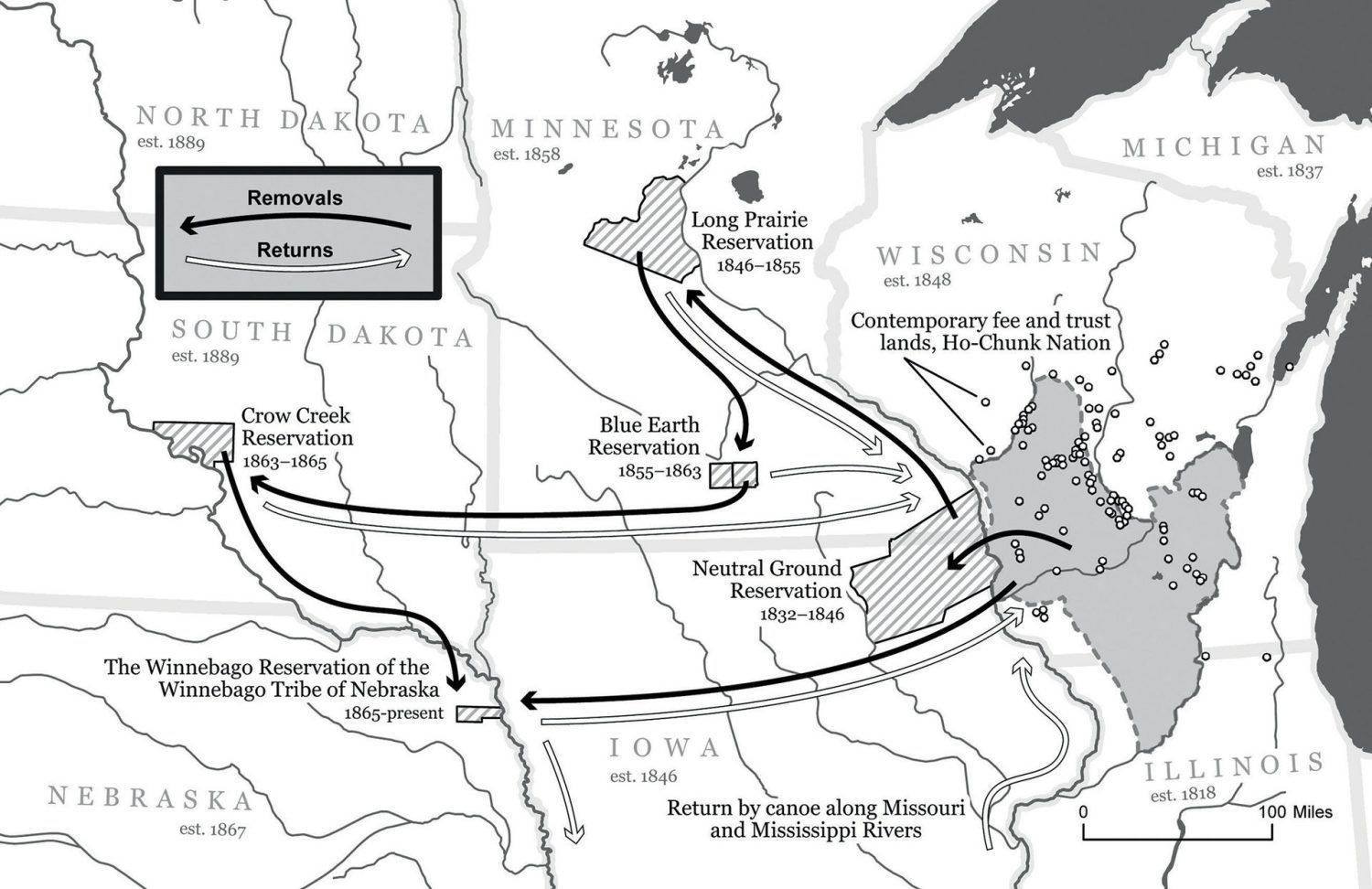

This removal wasn’t the first in the Ho-Chunk Nation’s history. The nation originated near Green Bay, Wisconsin, and occupied lands from there down to Northern Illinois. But between 1825 and 1837, the U.S. government and white colonizers coerced Ho-Chunk leaders into ceding their Wisconsin lands.

Over the next few decades, the U.S. military would round up Ho-Chunk people and force them from their homes. Amy Lonetree, a professor at University of California, Santa Cruz in the History Department and member of the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin, said that to understand their story of survival, people have to understand the reality of removals and the violence of settler colonialism.

She shared the testimony of John Blackhawk, the grandson of Chief Winneshiek, who lived through the removals and saw its horrors first-hand.

“Women and girls raped, men murdered, and all subjected to every insult and indignity that brutal men could invent. These outrageous things were inflicted upon the helpless victims for no other crime whatever, except that they had been unfortunate enough to be born Indians,” he said.

“That’s what happened to my ancestors. That’s what happened to my community,” Lontree said. “And that’s devastating as a scholar when you find those quotes. But it also inspires you. It obviously inspires you to make sure that this history is no longer ignored.”

The dominant narrative from the treaty and removal period is the Trail of Tears, when 60,000 people from the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from the southeastern United States, resulting in the deaths of 13,200 to 16,700 people.

“What the American public needs to understand is that there are many Trails of Tears. And for a nation like my own, the Ho-Chunk Nation, we were removed multiple times in the late 19th century, which resulted in great suffering and death,” Lonetree said.

The ethnic cleansing of Blue Earth County

The Ho-Chunk people were moved to the Blue Earth Reservation in 1855, but it was an unwelcome arrival for most white settlers in the county, who resisted the reservation at every turn.

Then came the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. The Ho-Chunk Nation was not involved in the war, but that didn’t curb colonizers’ anti-Indian sentiment and blood-lust. In January 1863, a group of men in Mankato created the Knights of the Forest, a hate group that sought to commit widespread ethnic cleansing by capitalizing on settler’s rampant racism and fear.

The members of this secret society were not vigilantes born from the fringes of Mankato. They were leading members of the community: bankers, politicians, lawyers, etc. Several would later become representatives in Minnesota’s state legislature.

“If you see anything about these men, it’s generally something positive and something about them being the town fathers. The Blue Earth County Historical Society, a decade ago, described them as rabble-rousers,” Coats said. “I don’t see them quite like that. I’d see them more as a hate group, and they really cost lives. Hundreds and hundreds of people died because of the Knights of the Forest.”

The Knights pressured the state and federal governments to carry out the removal, and during the winter of 1862 and 1863, they surrounded the reservation and threatened to shoot anyone who crossed over the reservation lines.

And their tactics worked. After the U.S.-Dakota War, Congress revoked all treaties with the Dakota, and in May of 1863, they were loaded onto steamboats and shipped to the Crow Creek Reservation in South Dakota. And alongside them were the Ho-Chunk people.

“Of all the removals that the Ho-Chunk went through, this one was the really the worst and the darkest one. The other removals were done by treaty. During this removal, they were ordered to leave by an act of Congress,” Coats explained. “There was no treaty, there were no negotiations. The Ho-Chunk people did not get a chance to speak on their own behalf during this removal. They were just ordered to leave, and then they were forced to leave at gunpoint.”

The Knights fizzled out after achieving their mission, but members still communicated and could recognize each other with a hand sign. Despite their secrecy, the group often bragged about their accomplishments.

“There’s a couple articles that were in the Mankato papers decades later, and they were kind of proud of it actually. They were like, ‘If it wasn’t for us, the Ho-Chunk people might still be here. We saved the town,’” Coats said. “A lot of people wanted to compare them to the Ku Klux Klan, which is a fair comparison in some ways. But as a historian, I saw a lot more parallels with the Holocaust, really. The putting them on boxcar trains, and the complete disregard for them as human beings.”

Reckoning with history

Coats first heard about the Knights of the Forest as an undergraduate history major at Minnesota State University Moorhead, while reading Winona LaDuke’s book, “Last Standing Woman,” which references the group.

“I was shocked that this happened, and that I grew up in Minnesota and had never learned about this history,” she said. “I had never even learned about the Dakota War until I was in college.”

And she’s not alone. When Amy Lonetree was a doctoral student in the early 1990s, she worked with the Minnesota Historical Society to research Ho-Chunk history for a Minnesota Communities exhibit. Prior to that moment, she didn’t know the history of Ho-Chunk reservations in the state or the forced removal in 1863.

“It is a very painful topic, and it is a topic that I don’t think the state has really reckoned with,” she said. “It is a story that needs to be told for our future generations as well, reminding us of the strength of our ancestors and the sacrifices that they made for us.”

Lonetree thinks people still aren’t familiar with Ho-Chunk history and their ties to Minnesota. Today, the state government formally recognizes 11 tribes in Minnesota, seven are Anishinaabe and four are Dakota.

Minnesota hasn’t acknowledged the deep and longstanding connection the Ho-Chunk people have with the state. Just in the Twin Cities, there are close to 1,000 Ho-Chunk people, and the nation has land trusts in southern Minnesota near La Crescent.

“I really hope that the book will inspire people to learn more about the history of Ho-Chunk people in Minnesota,” Lonetree said. “I hope in particular that the City of Mankato and people near Blue Earth County reckon with their history and understand that the dispossession of Ho-Chunk people, and the violence committed against Ho-Chunk people, made their world possible. And I think that that history needs to be examined and explored by the people of the state of Minnesota.”

Mankato has acknowledged its history with the U.S.-Dakota War. For the 150th anniversary of the war, the city planned plenty of commemorations, exhibits, and marches. But as Coats points out, there was no fighting in Mankato during the war. And throughout the anniversary, there was almost no mention of the Ho-Chunk people and their removal from the region.

“Mankato has done a lot for reconciliation with Dakota people over the war, but they have not done much for reconciliation with Ho-Chunk people or the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska,” Coats said.

‘It was genocide’

“It made the Knights of the Forest real. It wasn’t some guy telling stories in a newspaper.”

— Cathy Coats

Coats started researching the topic for her thesis as a graduate student at St. Cloud State University, under the guidance of her advisors Mary Lethert Wingerd and Iyekiyapiwin Darlene St. Clair (Mdewakanton Sioux Dakota), as well as Ho-Chunk historians and archivists.

The Minnesota Historical Society heard about her research from St. Clair, who had been working with the nonprofit on plans for the 150th anniversary of the U.S.-Dakota War. The organization reached out to Coats about turning her thesis into a book.

The process was long – about five years of thesis research and five years of pure book work – and heavy. Once she started working with Ho-Chunk people, the topic weighed on her. Reading about it in the library was hard, but hearing it from their descendants was harder.

“This is where being a white person, we can be allies, and we can carry some of the baggage,” Coats said. “I can help make an argument to the general public that this happened, that it was ethnic cleansing, that it was genocide, and that the Knights of the Forest was a hate group. This wasn’t just a war against Dakota people. There was more going on there.”

Researching a secret society meant relying on scant slivers of historical records, but Coats found her smoking gun document in the archives of the Minnesota State University, Mankato: the Knights of the Forest’s “Ritual,” a four-page pamphlet read aloud at meetings, containing the group’s initiation rites and oath.

The document had been sealed in a time capsule inside the cornerstone of the Old Main Building at the Mankato Normal School in 1869. Over a hundred years later, the Mankato State College Archives added the capsule to its collection, and in 2004, the university listed the capsule’s contents online.

No other copies of the ritual document are known to exist, and for Coats, seeing it in-person was a shocking moment.

“It made the Knights of the Forest real. It wasn’t some guy telling stories in a newspaper,” she said.

The Ho-Chunk people are part of Minnesota

Coats hopes this book will help Ho-Chunk people as they petition the state government for official recognition. And for the broader public, she wants people to learn about the still relatively unknown history of the U.S.-Dakota War and forced removals.

For Lonetree, “To Banish Forever” is unique in that it emphasized Ho-Chunk experiences and perspectives, but in the context of U.S. colonization, Manifest Destiny, and the forced removals of indigenous peoples across the continent, this history is painfully common.

People need to recognize that the privilege and generational wealth they enjoy today is a direct result of settler colonialism, which came at the expense and detriment of indigenous peoples, Lonetree said. And they must also realize that “we are nations, not minorities,” and that each nation has its own distinct culture and history, each deserving of careful and rigorous attention.

“The first step is to acknowledge it. So that’s why this text is so important,” said Lonetree, who reviewed the manuscript for the Minnesota Historical Society.

Especially with campaigns like Land Back and Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, as well as ongoing conversations about police brutality and environmental rights, Coats’ book is more relevant than ever.

Some members of the Minnesota Legislature are seeking to recognize the Ho-Chunk Nation as indigenous to the state. The Ho-Chunk people were here, Coats said. They’re still here, they’ve always been here, they are part of Minnesota.

“They just really want to be recognized in the state,” Coats said. “Institutional recognition matters.”

Several Ho-Chunk tribes are looking to distribute copies of the book throughout their communities, and elders are using the book to advocate for themselves before state and federal governments.

“This book needs to be in their hands, along with many other people from across Minnesota and beyond,” Lonetree said at the book’s launch. “I have not received a manuscript in recent memory that has the same level of relevance, necessity, and uniqueness as this one.”