I have been reading The Swerve: How the World Became Modern by Stephen Greenblatt (New York & London: W. W. Norton & Co., 2011) and enjoyed some of his invocations of the bookworm as one of the ultimate, slow and steady destroyers of material joy.

The first reference to these tiny creatures is part of a curse written in a medieval book found in a Barcelona monastery and aimed at the one who fails to return the book to its owner:

“let it [the book] change into a serpent in his hand and rend him. Let him be struck with palsy, and all his members blasted. Let him languish in pain crying aloud for mercy, and let there be no surcease to his agony till he sing in dissolution. Let bookworms gnaw his entrails in token of the Worm that dieth not, and when at last he goeth to his final punishment, let the flames of Hell consume him forever” (p. 30).

Wow! Let me assure you that we don’t curse people like this anymore in the libraries. Many academic libraries don’t collect overdue fines at all; and in fact, a public library in Worcester, Mass. has been gaining some fame lately by accepting cat pictures as a form of payment for library fines. In this spirit, I offer a picture of my most beautiful cat!

A more substantial meditation on the bookworm comes later in the text, when Greenblatt discusses what happened to the thousands of books that were produced in the ancient world. As he notes, apart from a small number of fragments, no manuscripts from the Greek and Roman world have survived. Everything we have is a copy, and thousands of works have been completely lost due to overuse, war, weather, changes in culture – and bookworms.

Greenblatt quotes the Greek poet Evenus, for whom “the bookworm was the symbolic enemy of human culture: ‘Page-eater, the Muses’ bitterest foe, lurking destroyer, ever feeding on thy thefts from learning, why, black bookworm, dost thou lie concealed among the sacred utterances, producing the image of envy?'” (p.84).

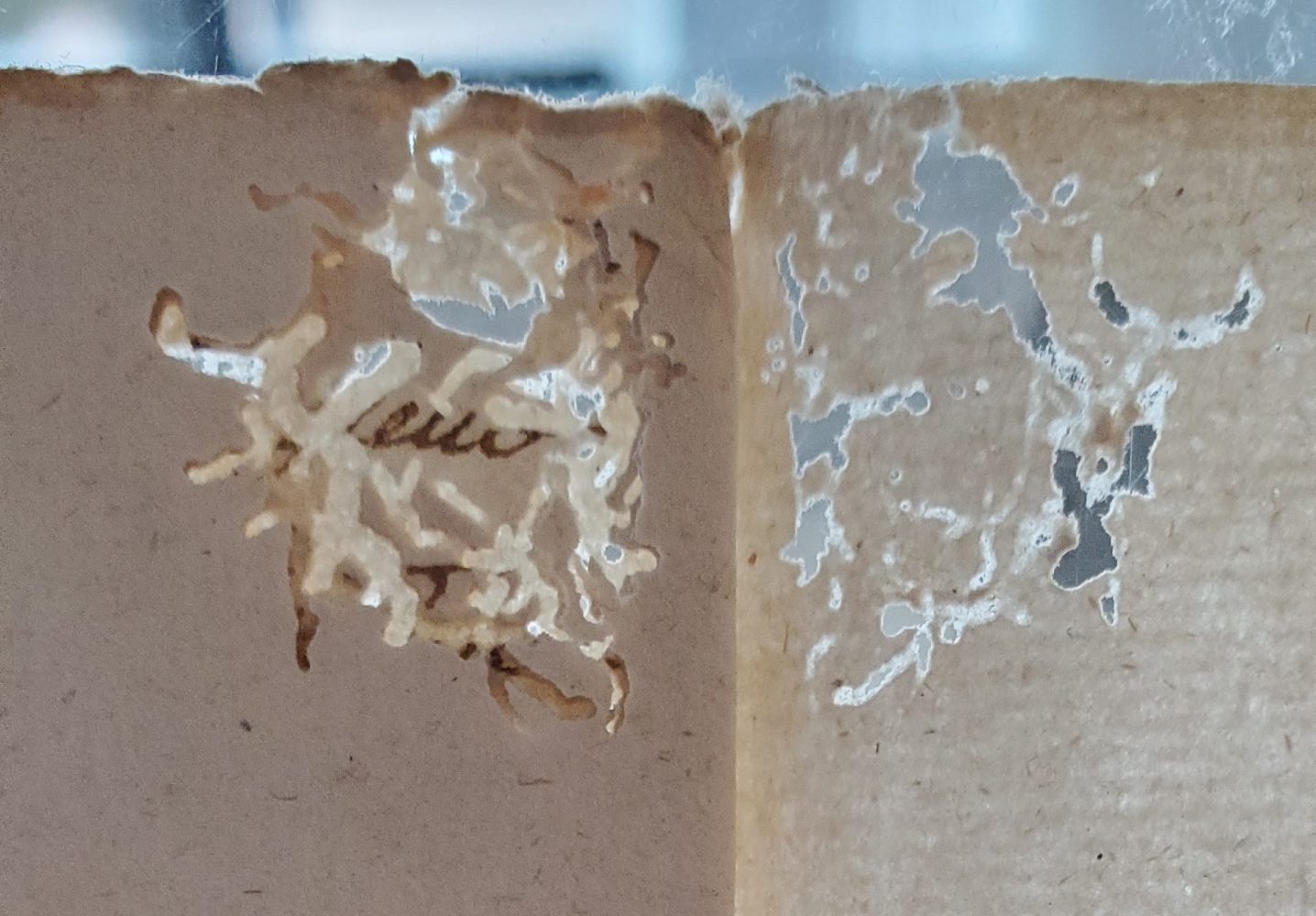

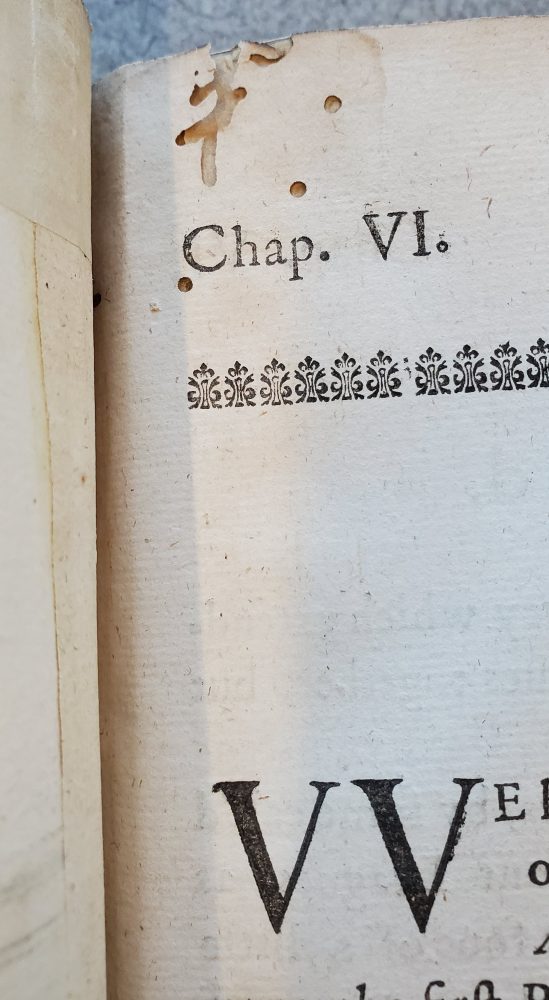

Bookworm damage from long ago in Reizen van Cornelis de Bruyn, door de vermaardste deelen van Klein Asia, de eylanden Scio, Rhodus, Cyprus, Metelino, Stanchio, &c. (Delft, 1698). Bell Call # 1698 fBr.

In the ancient world, the only known protective remedy was to sprinkle pages with cedar oil. Now, clean, climate-controlled vaults protect vulnerable materials. We obviously have no active infestations in the Bell Library, or in the Archives and Special Collections (ASC) at the U of MN in general. New collections that come to ASC from musty basements, humid attics, or sketchy garages are always quarantined and thoroughly checked for insects before any kind of processing is done. But, we do come across bookworm damage from time to time – from at least decades, but probably centuries ago. The traces of these tiny insects can be very artful.

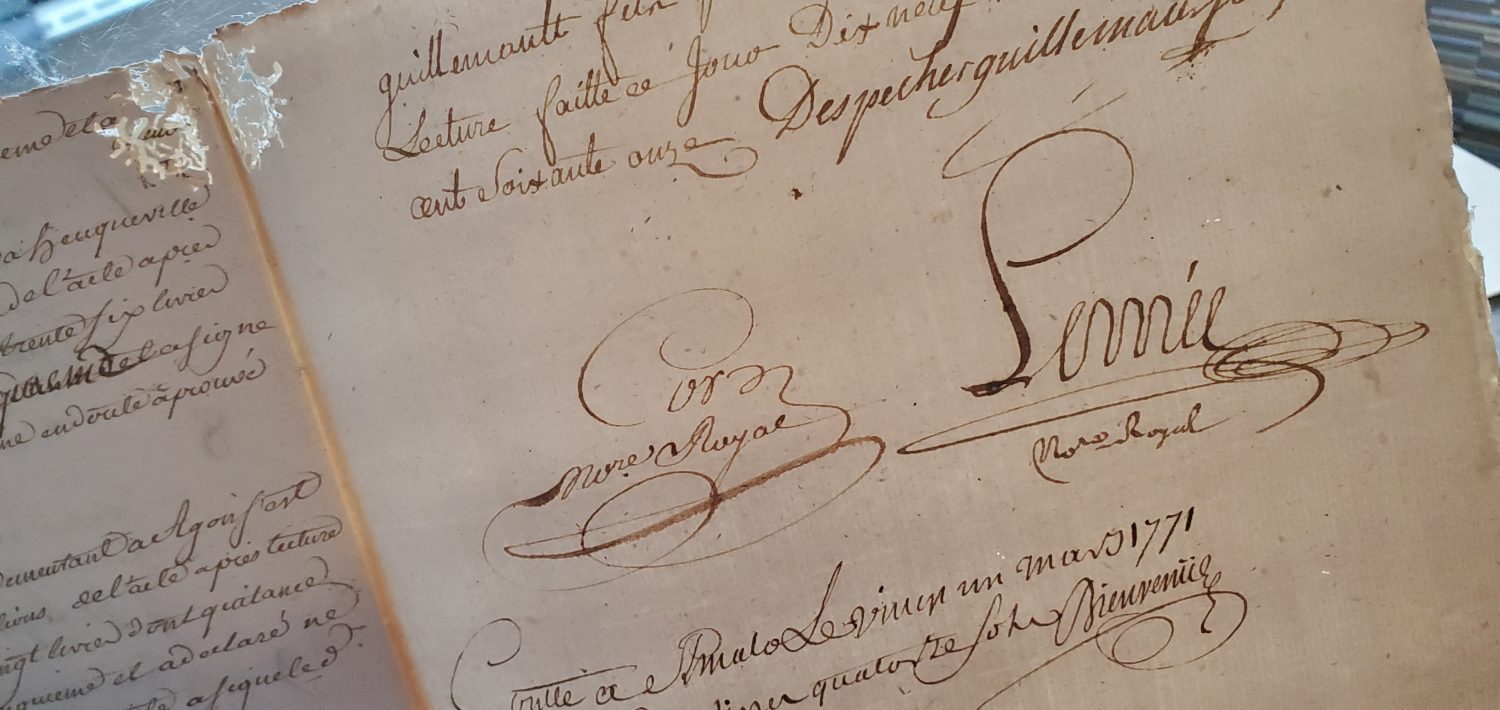

Contract for a fishing vessel, signed at Saint Malo, France, March 1771. Bell Call # 1771 De. The full document may be viewed here on the UMedia platform.

In the interest of science, I should note that “bookworms” are not actually a species of worm, but could be a variety of different insects, including various beetles or their larvae, lice, termites, moths, and, my least favorite, cockroaches. Most of these are less interested in the paper as such, and more interested in consuming microscopic fungi and molds, as well as the glue, cloth, and leather that hold books together.

The Swerve celebrates “De rerum natura” (“On the Nature of Things”) by the Roman poet, Lucretius (ca. 99-55 BCE), which was rediscovered in a medieval manuscript copy in a German monastery by the Italian humanist, Poggio Bracciolini (1380-1459 CE), in the early 15th century. The poem is in the Epicurean tradition and is an exposition of materialist philosophy. Greenblatt argues that the rediscovery of “On the Nature of Things” had a profound affect on the whole course of the modern world, and thus, though books and people pass away, ideas go on.