By Anne Good, Assistant Curator

Most biologists agree that a “sixth extinction” is currently underway due to human activity in the natural environment. Just how far into it we are is a matter of debate, but the signs are alarming. Beautiful Newfoundland is one of the places we can look to for evidence of a natural world changing virtually before our eyes.

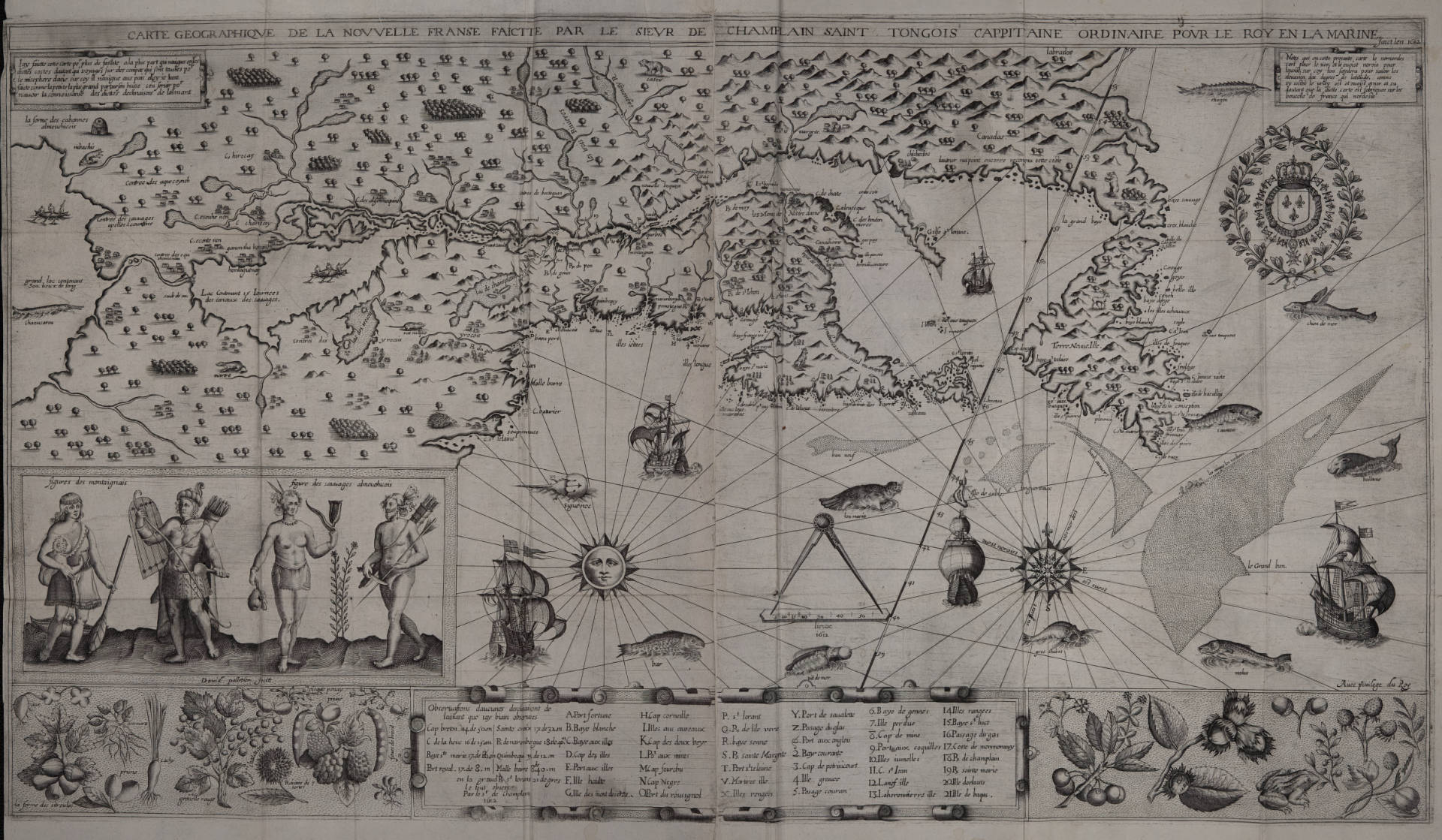

Maps of Newfoundland from the early modern era portray an abundance of nature. All kinds of interesting creatures appear on the land and in the waters. This map, by Samuel de Champlain from 1632 (Bell #1632 Ch c1), focuses on the great variety of plants that could be found on land in northeastern Canada, as well as fish in the sea. There’s even a very realistic seal in the water.

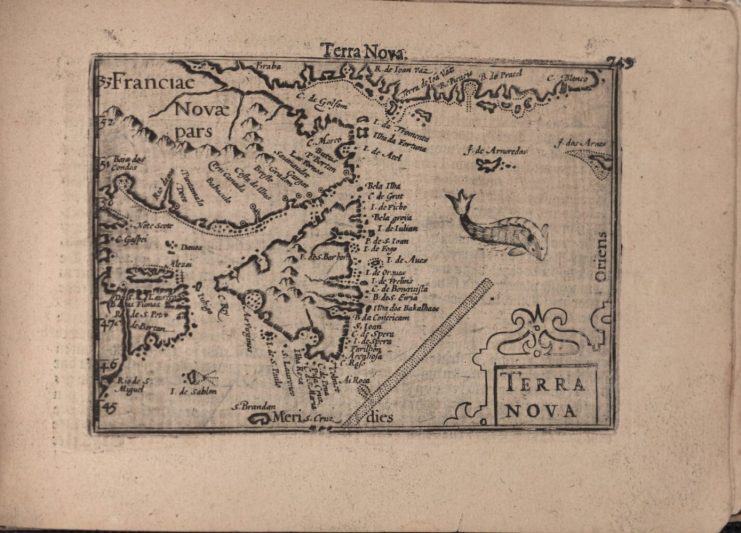

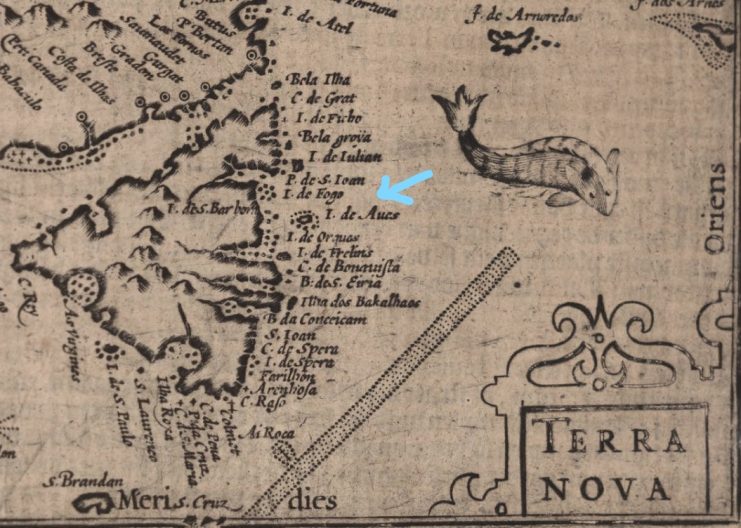

Place names on the maps make you think of loads of wildlife too. There are references to various fish (for example, Port aux Saumons) but most commonly variations on the word for cod (bacalhao, bacaillou, baccalieu, etc.) – the island’s main export. Birds too are everywhere on the maps. This blog post was originally inspired by a reference I spotted, on a very early Dutch map of Newfoundland by Jacobus Viverius (Bell #1609 sVi): “I. de Aucs.” Great Auks certainly flourished in the north Atlantic in the early modern era.

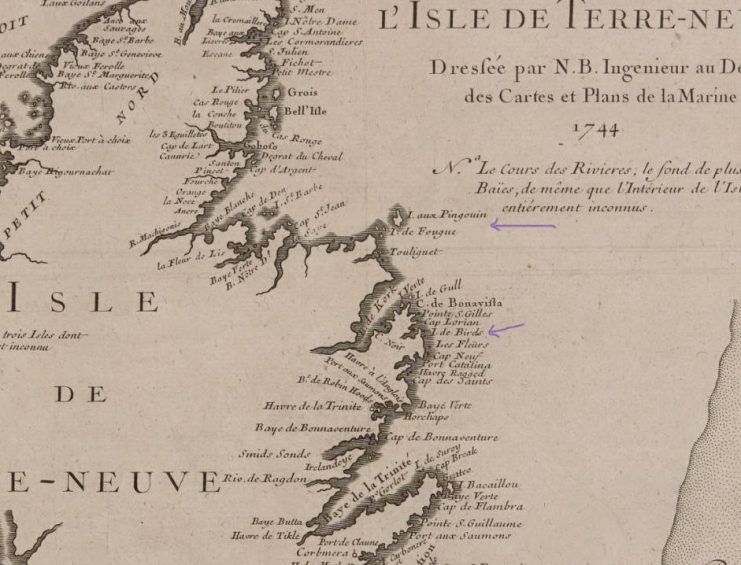

An 18th-century French map by Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix (Bell #1744 Ch v.1), also shows: “Les Cormorandieres” and “I. aux Pingouin” among others. In this case, the “penguins” are in probably Great Auks too.

There is evidence too that, further back in time, the bills of Great Auks were used by paleo-Eskimos and/or early Inuit and Innu peoples on the island for hunting, fishing and possibly as ritual objects. These beaks are on display in the Paleo-Eskimo interpretive center at Port au Choix.

“I. de Aucs” and Charlevoix’s “I. aux Pingouin” are both next to present-day Fogo Island, formerly a known nesting ground of the Great Auk. Great Auks were prized by Europeans for their large size, fatty meat, and black and white feathers. They were slow-moving and easy to catch in large numbers. Their large eggs were also consumed and chicks were used as bait for fishing. With all this unbridled consumption, sadly, the Great Auk was hunted to extinction around 1844.

This is the memorial to the Great Auk on Fogo Island.

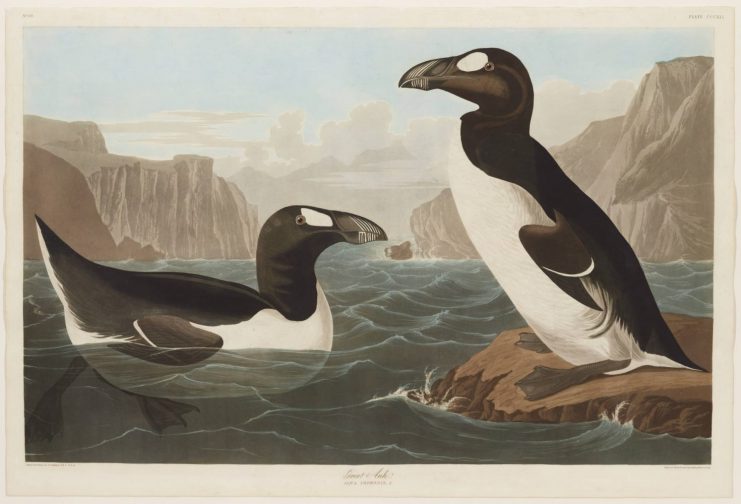

This painted image is from the Bell Museum’s Audubon album (bellmus341). Audubon never actually saw a living Great Auk, but created his painting based on a stuffed one that he was given by a friend. That stuffed bird eventually made it into the collection of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, together with a stuffed extinct Labrador Duck.

Finned sea creatures have also suffered through contact with humans. In the 18th century, whalers would still claim that there were so many whales in some northern bays that a man could run across their backs for more than a mile. Whale oil was highly prized. Among the most docile and blubber-rich species was the North Atlantic Right Whale. This species, which ranges from the Labrador Sea to the coast of Florida and Georgia is now down to a population of just 336 individuals.

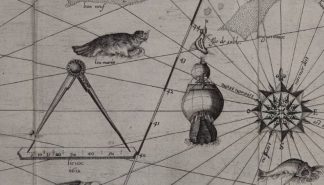

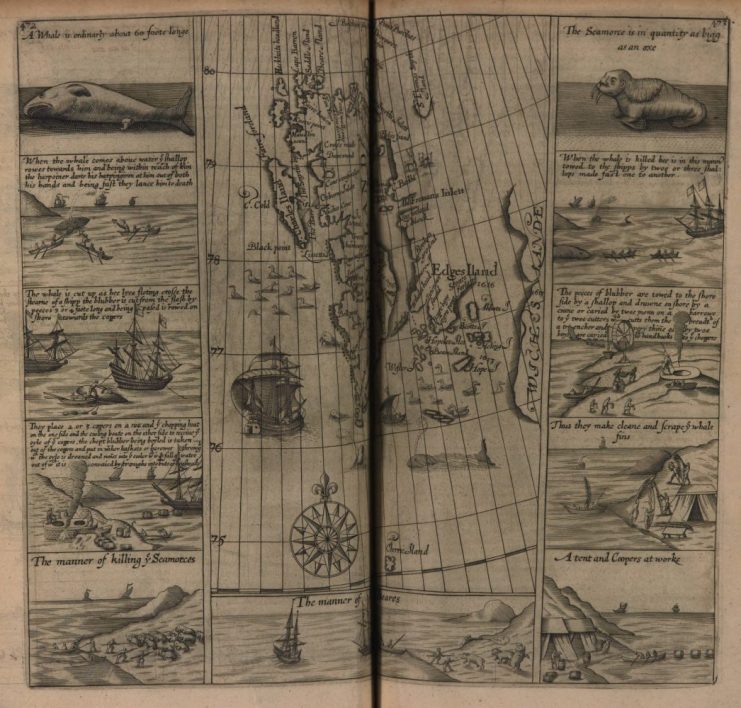

This spread of images comes from Purchase his Pilgrims (Bell Call # 1625 fPu v. 3 (p. 472-473) and depicts whaling and hunting walruses and polar bears near Greenland.

You can listen to North Atlantic Right whale calls here.

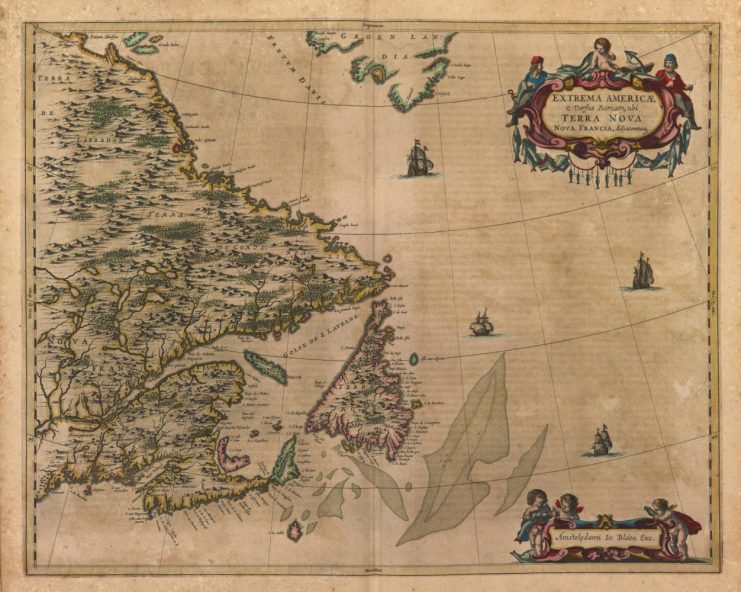

Most of all, Newfoundland was known for rich cod-fishing waters in the early modern era. The Grand Banks off the east coast of the island were known as the “mine of the sea” for waters teeming with cod. Cod was big business in the entangled Atlantic world, and a way of life for Newfoundlanders. The map below, Joan Blaeu’s, “Terra Nova” from Le Grande Atlas (Amsterdam, 1667) (Bell #1667 oBl v. 12), emphasizes the wealth of fish.

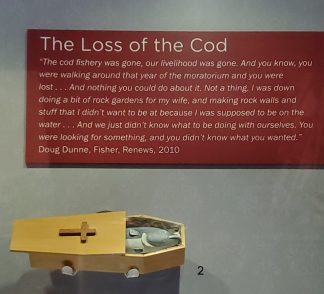

This too changed completely. Commercial over-fishing from the 1950s onward, caused the size of the fish to decrease over time, and the population of this fishery to drop dramatically from the 1970s through to a collapse in the early 1990s. The Canadian government declared a moratorium on fishing in 1992. This has been extremely painful for Newfoundland, but the cod population has not rebounded.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though. The Canadian government strongly supports conservation efforts, and Newfoundland is committed to protecting several north Atlantic bird colonies. The incredible bird rock at Cape St. Mary’s Ecological Reserve can be easily viewed by hikers.