By Allison Campbell-Jensen

Student Darby Ronning was immediately fascinated by the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine. “She’d first learned about the Wangensteen when she visited during a prospective student weekend,” says Assistant Curator Emily Beck, “and couldn’t wait to find an opportunity to come back and spend more time in the collection.”

During that 2019 tour sponsored by the University Society of Women Engineers, Ronning was excited to see historic books on women in science and medicine — and to be able to leaf through the pages of these old books.

“The library just seemed like a great place for education, showing aspects of history and getting to be hands-on with it, too,” she says. After Beck and Curator Lois Hendrickson presented remotely to her Age of Curiosity class in fall 2020, Ronning decided to pursue her fascination and emailed them.

“I know everything is weird right now with coronavirus, but I would be super interested in working with the rare books archive.”

Says Beck: “We love having students work with us and the Wangensteen collections to create amazing online exhibitions using StoryMaps.” Ronning is a dual history and statistics major, Beck notes, so she “brought a ton of useful experience and lots of curiosity and willingness to dig into our collection materials.”

Beck and Hendrickson agreed to do a directed study with Ronning. Her unusual double major coincides with a surge in computational history scholarship, Hendrickson says, and “we wanted to see if we could find a project that would allow her to develop skills in that arena — i.e., how to use statistics for a public audience that would tell a story.”

They considered research on a 1790 plague in France, Hendrickson says, because the library has a good collection and Ronning reads French, or perhaps a project on plagues in England. But ultimately, they chose the letters of James H. Stuart, a young physician on the North Pacific Exploration Expedition. The letters are digitized, so the project could pivot to remote access, if needed due to COVID.

Sailing into the letters

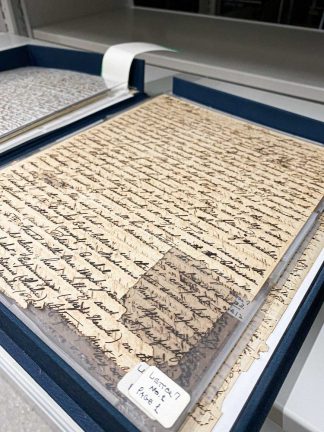

letters of James H. One of the letters of James H. Stuart, a young physician on the North Pacific Exploration Expedition.

Stuart, born in 1828, started writing to his mother while in medical school in Pennsylvania. When he began the position as Assistant Surgeon on the ship Porpoise in 1853, he had to keep journals on board for his duties as physician, naturalist, and meteorologist. But he was forbidden to keep a personal journal, so letters to his mother served in its place. He was able to send letters from ports where the ship docked on its way east from New York around the Cape of Good Hope and to the Pacific.

Initially, Ronning was a bit overwhelmed by 49 letters held by Wangensteen.

“I just started reading the letters, not really knowing where I was going with it,” she says. As she read, she saw a possible research focus examining what Stuart wrote about his medical practices. Analyzing his network of interpersonal relationships also could be interesting. And pirates threatening the expedition near Hong Kong were intriguing to Ronning — although Stuart was ultimately disappointed. Assigned to lead a crew, he wrote: “I very much fear we will see no pirates & have no action.”

On the voyage from Cape Town to Hong Kong, bird enthusiast Stuart did see plenty of birds, however, and his sightings could be matched with navigational coordinates. “I thought that was a really interesting way to bring a bit of statistics and numbers into that,” Ronning says, “and also attach it to something a little more interesting to the general public, like looking at the locations of these birds.”

Discoveries at sea

“To see the points mapped out — to see that it made a cohesive line that you could really tell this was the route that the ship took — it made the project so much more real to me.”

—Darby Ronning

Ronning was excited to handle the actual 32-page letter that Stuart wrote during that portion of the trip. She was able to take the minutes and seconds figures used in the 19th century to describe position at sea, put them into a spreadsheet, and did the math to convert them into decimal degrees.

“Then I was able to put them into our GIS story map,” she says. “To see the points mapped out — to see that it made a cohesive line that you could really tell this was the route that the ship took — it made the project so much more real to me.”

Then she had the challenge of identifying the birds that he saw.

“Finding the resources initially was a little tricky because I didn’t have a ton of background,” says Ronning, who is not a birdwatcher. In addition, species names have changed over time. She used books from around 1900 on birds of the area and a contemporary article cataloging finds from the expedition — as well as comparing the places where they were sighted to habitats described in today’s IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Along with tracking down the Brown-browed Albatross by comparing name changes over time, she noted the Olive Bush-Shrike in southern Africa, and the “Leach’s Storm Petrel,” now known scientifically as Hydrobates leucorhous. “The location that James witnessed this bird is on the very edge of its habitat, so perhaps its habitat has shrunk since 1853,” Ronning wrote in her online exhibit Birds of the North Pacific Exploration Expedition

She was not able to pin down the modern bird that corresponds to Stuart’s Violet-headed Creeper. Still, the overall project is worthwhile, says Beck: “The result is a really interesting case study on how scholars can use historical data to study the history of ecologies and climate change.”

For her work on the online exhibit, Ronning received a 2021 U-Spatial Mapping Prize for Undergraduate Student — Best Representation of Research, from the University of Minnesota.

Ronning did encounter challenges reading letters from the 1850s.

“It’s so cool that we have them at all but some of them are in really sorry shape,” she says. “Sometimes, I was trying to read through but there’s a whole chunk missing from the paper. I can tell he’s going to say something interesting or he’s about to talk about another bird — but the paper has deteriorated. We can’t read it and that’s always a little disappointing.”

Lost at sea

Other ships of the expedition continued on but, following their stop in Hong Kong, the Porpoise was lost at sea and the crew, including James Stuart, presumed dead. Still, Ronning primarily used one very long letter for her research, so there are more to explore.

And there’s more to explore at the Wangensteen Library, too, once it re-opens in mid-August. “If I hadn’t gone to the Wangensteen when I toured, I probably wouldn’t have known about it at all,” Ronning says. “I just want to encourage everyone with the slightest interest in history or medicine or biology to stop by. They have a lot of cool texts and artifacts.”

Sidebar:

This summer, the Wangensteen Historical Library of Biology and Medicine is closed while completing its move to a new space in the Phillips-Wangensteen Building. It is slated to re-open on Aug. 16.