As premodern voyagers returned from overseas expeditions, bringing strange tales from strange lands, their perspectives changed how Europeans viewed the world and their relationship to it.

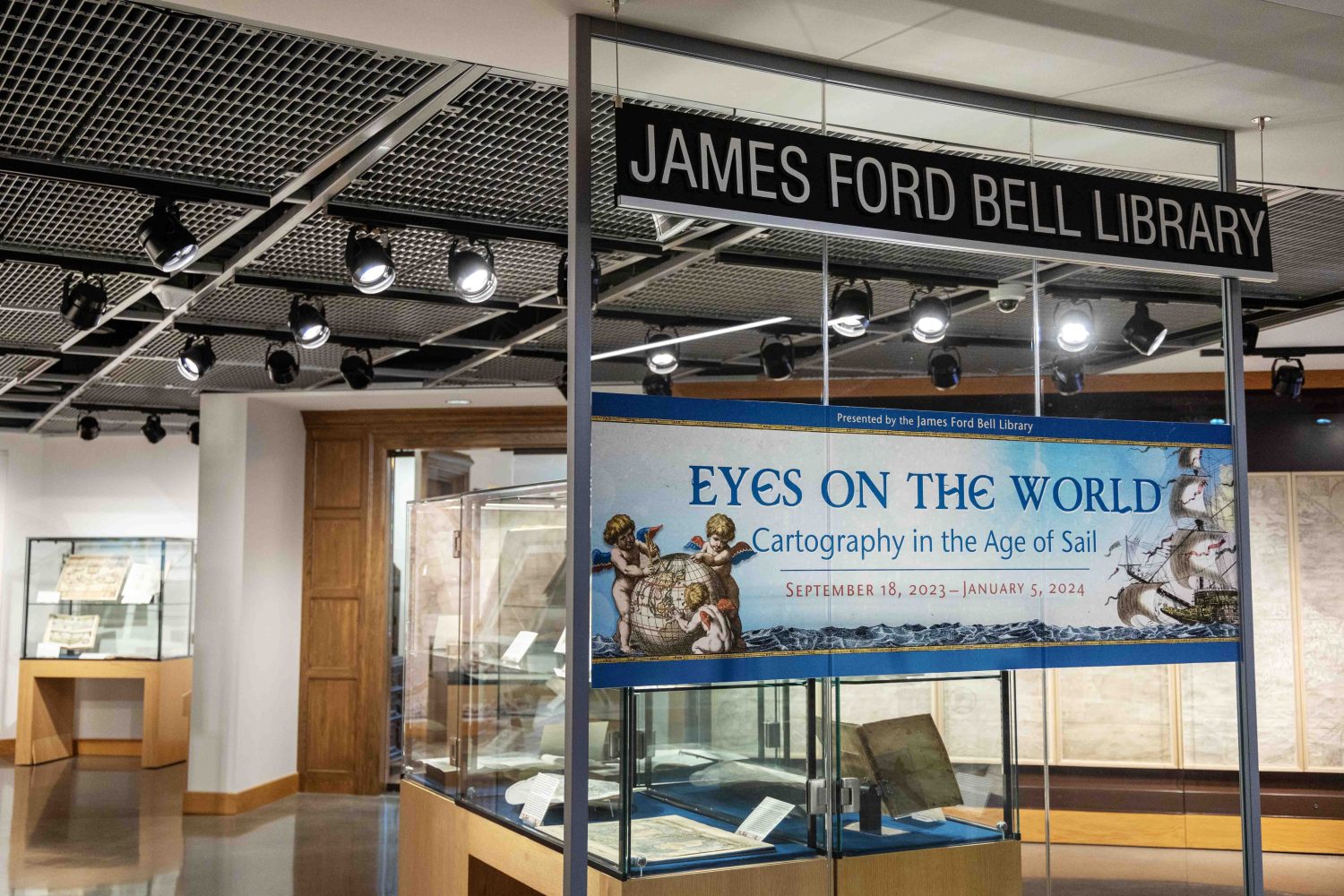

The James Ford Bell Library’s newest exhibit — “Eyes on the World: Cartography in the Age of Sail” — reveals the ever-shifting outlooks on the globe throughout the 15th and 18th centuries.

“World maps, more than anything else, are reflecting how people’s ideas about the world are changing over time,” said Marguerite Ragnow, curator of the Bell Library.

Ragnow and Assistant Curator Anne Good were inspired by the Bell’s collection of pre-modern atlases, which have never been showcased in an exhibit before. With more than 22,000 maps in the collection, Ragnow and Good struggled to choose which ones to display. But after a year of planning and three weeks of preparation — working alongside Exhibit Designer and Project Specialist Darren Terpstra — the team narrowed it down.

“We have way more materials than we could show. We could do this same theme and have the cases full of different things,” she said.

“A New and Correct Map of the World, Laid Down According to the Newest Discoveries and from the most Exact Observations,” by Herman Moll, photographed on Friday, October 6, 2023. Exhibit designed by Darren Terpstra, exhibit designer and project specialist. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

While many of the atlases were simply too large for the exhibit’s display cases, the smaller books and maps feature famous names in the history of cartography, like Claudius Ptolemy, the father of modern geography, or Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit priest and creator of the earliest known, European-style world map written in Chinese.

The exhibit features a mix of black-and-white and hand-colored maps. Each display case is built around a particular theme, like maps of islands, travelers who circumnavigated the world, Jesuit cartography, etc.

One of Ragnow’s favorite items is a hand-colored, manuscript map of Siberia, created by Danish explorer Vitus Bering in 1729. Bering sought to map the extent of the Russian empire, and to learn how close Russia was to North America.

“It has ethnographic drawings in the center of it, and the whole thing is colored. It’s just a very lovely map that represents a very important expedition,” she said.

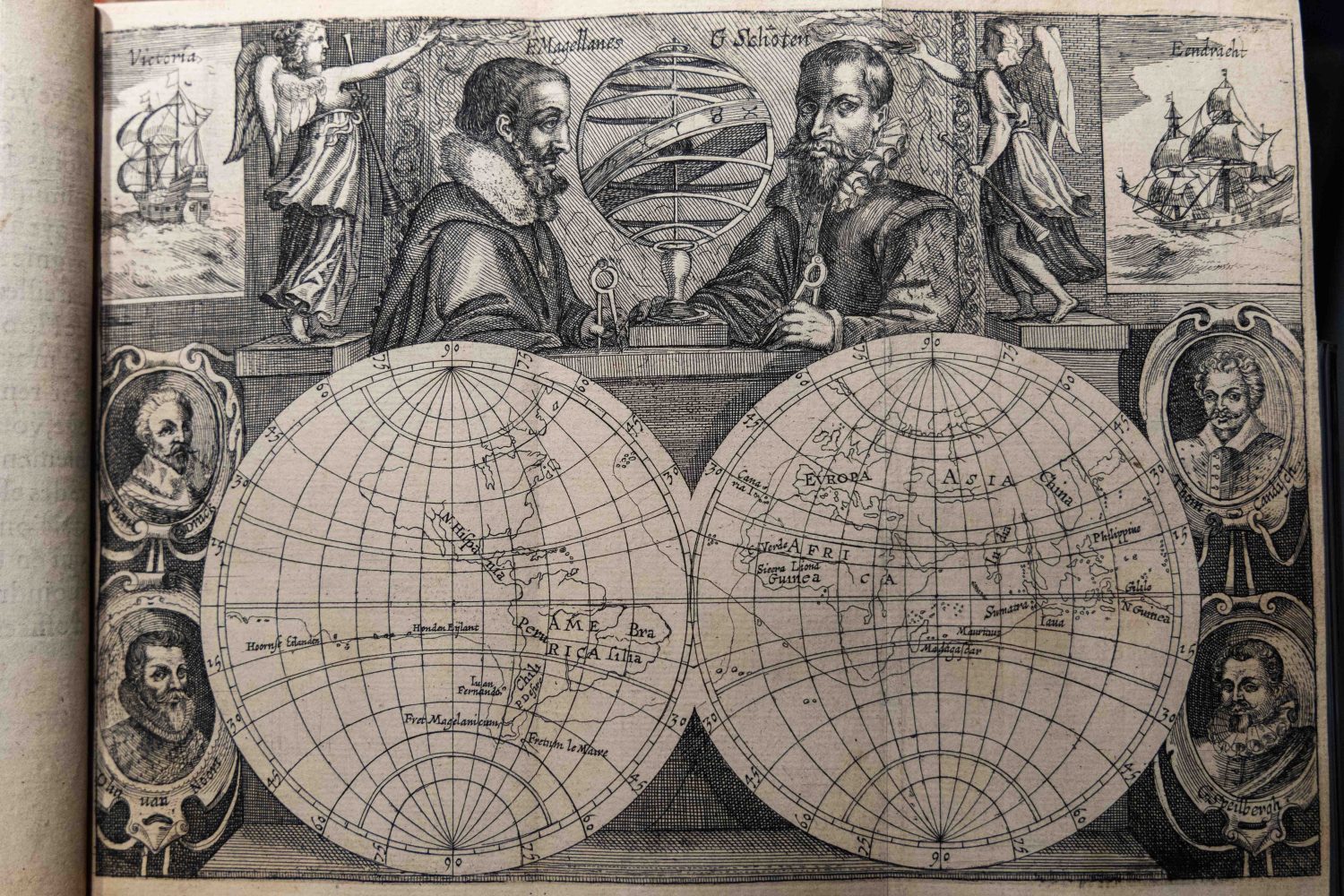

Meanwhile, Good particularly enjoys the cases highlighting the voyages of circumnavigators from 16th to the late 18th centuries.

“I love the maps that show the tracks of these expeditions like small threads of discovery wending their way across vast oceans,” Good said.

Hendrick Doncker’s “De zee-atlas ofte water-waereld, vertoonende alle de zee-kusten van het bekende deel des aerd-bodems, met een beschrijvinge der selve : seer dienstigh voor alle schippers en stuerlieden, mitsgaders Kooplieden om op ‘t kantoor gebruyckt te werden : nieuwelijcks aldus uytgegeven,” photographed on Friday, October 6, 2023. Exhibit designed by Darren Terpstra, exhibit designer and project specialist. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

While some maps will look familiar to modern viewers, others will look a little strange. For example, one 18th-century map depicts California as an island.

This illustrates a common misconception people have about premodern maps, Ragnow said. People assume that maps chronologically improve over time, that examining maps from different eras will show a progression of geographic understanding.

But maps from this period are highly subjective. They’re dependent on the individual cartographer and printer, the precedents on which they relied, and the available knowledge they had. Maps are also shaped by people who commissioned them, and their personal motives.

Jesuit missionaries commissioned and created maps to serve their mission to Christianize the world. Wealthy people often bought maps and atlases as status symbols. Universities bought large, expensive sets for scholars and students, while smaller volumes circulated for general populations. Still other maps were printed and distributed to attract investors for expeditions.

“In many cases, you’re getting one person’s geographic perspective transferred onto a map,” Ragnow said.

Gerhard Mercator’s “Gerardi Mercatoris atlas sive cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura,” photographed on Friday, October 6, 2023. Exhibit designed by Darren Terpstra, exhibit designer and project specialist. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

Typically, voyages would employ a few draftsmen to create sketches and rough maps. These were subsequently sent to a publisher or printer, who assembled that information from three or four different maps. Occasionally, the printer would edit the maps, depending on their preferences or experiences.

So like the California map, some representations are less accurate than those from two centuries prior. And other publications, like the Ptolemy atlases which started being printed in the 15th century, displayed outdated maps alongside updated maps.

“So they don’t let go of the classical information even if they now have new information,” she said. “It’s a different way of looking at the world. It’s not perceived as static.”

As geographic information became more universal, the maps became more standardized, but that process took hundreds of years.

“A New and Correct Map of the World, Laid Down According to the Newest Discoveries and from the most Exact Observations,” by Herman Moll, photographed on Friday, October 6, 2023. Exhibit designed by Darren Terpstra, exhibit designer and project specialist. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

Subjectivity of early mapmakers

Today’s maps are designed to get us from point A to point B, and are more mathematically accurate thanks to new technology and GIS data. But premodern maps, by contrast, weren’t necessarily created for accuracy or travel. They represent the creators’ and viewers’ relationship to the rest of the world.

“It’s the subjectivity of maps during this period that really gets the modern viewer, because we’re not used to thinking of maps as subjective objects,” Ragnow said. “Early modern maps only show the extent of geographic knowledge accessible to the person who made the map.”

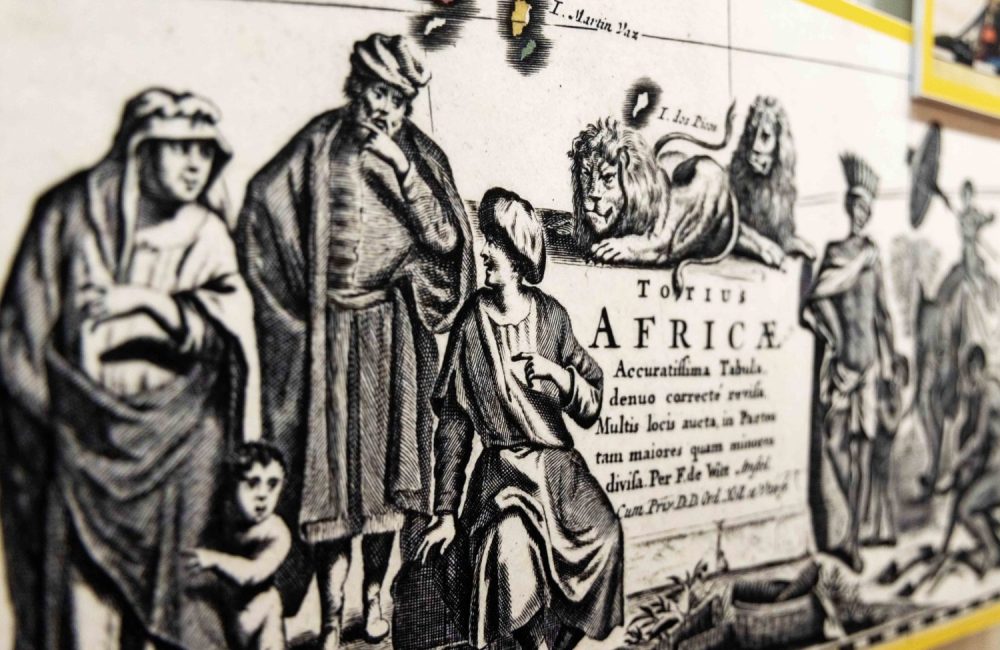

The companion exhibit, “Curious Strangers,” on display in the Bell Room, further illustrates the subjectivity of mapmakers. The exhibit creates collages of different peoples and cultures, as depicted in early modern maps.

“During this period, everybody who wasn’t related to you, or wasn’t in your neighborhood or your town, was a stranger,” she said. “Your own personal universe was very small.”

For people who lived in Italy, people from Norway were as strange and exotic as people from South America. So people learned about other cultures from maps and travel narratives, which were often exaggerated and sometimes fabricated.

Jacques Le Maire’s “Spieghel der australische Navigatie” from 1622, photographed on Friday, October 6, 2023. Exhibit designed by Darren Terpstra, exhibit designer and project specialist. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

Ragnow also admires how beautiful these maps are as displays of art and printing technology. Many of the exhibited materials are engravings, which were created from sketches that are cut backwards onto the surface of a plate. And color maps were painted by hand.

“It takes many people to actually produce an atlas, but even quite a few people to produce a single flat map,” she said. “These people have a lot of skills for which we now rely on technology, and that’s amazing.”

Where and when to see the exhibit

“Eyes on the World” will run through Jan. 30, 2024, in the Bell Gallery on the ground floor of Elmer L. Andersen Library. The exhibit is open during normal library hours (9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Monday, Tuesday, and Friday; and 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. on Wednesday and Thursday). After Thursday, Nov. 23, the library will close at 6 p.m. on Wednesdays and Thursdays.

Scenes from the James Ford Bell Library’s latest exhibit, Eyes on the World, featuring maps and atlases produced by cartographers and printers from the 15th to 18th centuries, photographed on Friday, October 6, 2023. Exhibit designed by Darren Terpstra, exhibit designer and project specialist. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)