“I was arrested for taking this railway scene. Starved peasants wait weeklong for trains to some objective they vainly imagine is the Promised Land where they may find enough food to keep alive,” wrote photographer James Abbe. Image reproduced courtesy of The James Abbe Archive.

Zina Poletz Gutmanis grew up in the Twin Cities’ active Ukrainian community, attending St. Michael’s and St. George’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church with her family. But as a child she’d never heard about the Holodomor, a man-made famine in Soviet-occupied Ukraine that killed millions of people.

When she saw the 1985 documentary “Harvest of Despair,” she was left stunned and speechless. But it still felt disconnected from her life, and the lives of the people around her.

“Just a few years ago, I was talking to my mom, and she was like, ‘You know that your grandparents lived through the Holodomor, right?’” she said.

Gutmanis was close with her grandmother but hadn’t heard the stories. In 1932, her grandmother, then 11 years old, quit school to work in a sugar beet processing factory to help her parents, who were struggling under the Soviet Union’s collective farming policy, which seized land and livestock from farmers and imposed unreasonably high taxes and grain quotas. Gutmanis thinks her grandmother was trying to protect her by staying silent.

That experience planted the seed for Gutmanis’ new documentary, “Holodomor: Minnesota Memories of Genocide in Ukraine,” which was screened at Andersen Library last month, alongside a panel presentation about the Ukranian holdings in the Immigration History Research Center Archives (IHRCA).

The documentary asks, how is the memory of collective trauma transmitted, and how is it concealed?

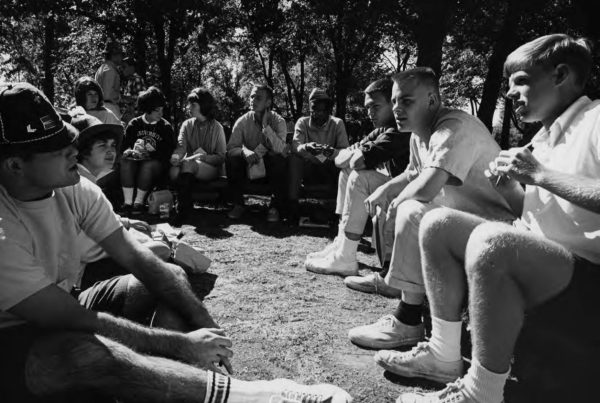

- Zina Gutmanis holds a screening of her new documentary short, “Holodomor: Minnesota Memories of Genocide in Ukraine,” at Andersen Library on Tuesday, March 19, 2024. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

- Attendees clap at a screening for the documentary short, “Holodomor: Minnesota Memories of Genocide in Ukraine,” at Andersen Library on Tuesday, March 19, 2024. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

Death by hunger

For much of its modern history, Russia and the Romanov Tsars occupied Ukraine, annexing land, imposing serfdom on its citizenry, and implementing Russification policies, which restricted Ukrainian language and culture in an attempt to suppress their emerging national identity.

Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, Ukrainian leaders quickly established a new independent government in Kyiv, the Ukrainian People’s Republic, but it was soon defeated by the Bolshevik Red Army.

Chairman Vladimir Lenin implemented two policies, the New Economic Policy and Indigenization, designed to aid independent farms and businesses and promote Ukrainian national and cultural liberalization.

- Queue for milk, which in 1933 was only available by medical prescription for children and for the sick. (Photo/Alexander Wienerberger)

- A group of homeless children on a rock pile in Kharkiv, summer 1933. (Photo/Alexander Wienerberger)

But when Joseph Stalin assumed control of the Soviet Union, he tightened his grip on Ukraine, undermining its economic and cultural independence. The Soviet Union arrested and executed Ukrainian intellectual leaders – artists, educators, religious leaders, etc. – and instituted agricultural collectivization

State police and brigades went door-to-door, confiscating any food they could find. Those who couldn’t meet the grain quotas were forced to turn over their livestock. Collective farms that failed their quotas were blacklisted and had to surrender 15 times their quota.

Anyone caught taking food from collective farms could be imprisoned or executed. The Soviet Union closed Ukraine’s borders, and started an internal passport system, preventing anyone from leaving the country, or even their village, in search of food.

Victim of starvation lies dead against the side of a building in Kharkiv, spring-summer 1933. (Photo/Alexander Wienerberger)

In June of 1933, at the peak of Holodomor (which means “murder or torture by hunger” in Ukrainian), around 28,000 people died every day, according to the University of Minnesota’s Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

The Soviet leadership seized 4.27 million tons of grain from Ukraine in 1932, enough to feed 12 million people for at least a year and exported much of it. Soviet leaders denied foreign aid, filled mass graves across the countryside, and buried the cause of death in their official records.

“The resilience of the Ukrainian spirit amazes me. After centuries of oppression, repression, conquest, and genocide, it’s amazing to me that Ukraine and its people are still here,” Gutmanis said.

Overcoming the silence

Gutmanis wanted the documentary to stay rooted in the Twin Cities, and to explore not just the Holodomor, but how people coped with, commemorated, discussed, or taught the Holodomor.

From the 1930s onward, Ukrainians in Minnesota organized to bring attention to the Holodomor, holding awareness events and petitioning the local, state, and federal governments to provide relief.

“In the 1930s, Ukrainian Americans used all means at their disposal to call attention to the famine. They were putting on concerts and performing all over the place, at Northrop Auditorium, at any organization that would invite them,” she explained. “They were appealing to lawmakers to alert the American public and politicians to Soviet crimes.

- In all stages of starvation, spring-summer 1933. (Photo/Alexander Wienerberger)

- A young girl wearing a traditional white head scarf lies dead and alone on a set of stairs near one of the rivers that intersect Kharkiv, spring-summer 1933. (Photo/Alexander Wienerberger)

Two Minnesotans were among the first to document this genocide. In 1953, Dmytro Solovey, who immigrated to St. Paul after World War II, published “The Golgotha of Ukraine,” the first English-language compilation of Holodomor survivor stories. Then in 1985, Slavko Nowytski, who also lived in St. Paul, directed “Harvest of Despair,” the first documentary about the Holodomor.

Gutmanis sought to create a space for compassionate conversations about this grim chapter in Ukraine’s history. The Soviet Union denied the genocide and any mention of the Holodomor could result in arrest, so many survivors kept silent, or talked in secret.

In the United States, for example, when the U.S. Commission on the Ukraine Famine collected survivor testimony, most agreed to share their stories only under a pseudonym, fearing retaliation either against them or family members who still lived in Ukraine.

Lastly, Gutmanis drew historical parallels between the Holodomor and the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, showing a pattern of Russian aggression, occupation, and desire to erase the Ukrainian national identity.

Researching in the archives

Gutmanis was inspired to work on the documentary after completing an oral history project with local Holodomor survivors, as well as their children and grandchildren, in 2019. The project, funded by the Minnesota Historical Society, is currently housed in the Immigration History Research Center Archives (IHRCA).

“Here were these people that I had known who they were all my life, but I had never had this kind of in-depth kind conversation about their past. And I learned so much that I didn’t know, and it really sparked this interest for me,” Gutmanis said. “And I was just doing all this research during the pandemic, and I just decided to go for it and make a film.”

With a grant from the Minnesota Arts and Culture Legacy Fund, Gutmanis began working on the film. “Holodomor: Minnesota Memories of Genocide in Ukraine” is her debut as a filmmaker, and while the nearly three-year production was slowed by trial-and-error, she’s happy with the finished product.

Gutmanis spent over a year, relying heavily on the IHRCA. In addition to interviewing Holodomor survivors and descendants, she also interviewed several historians, including Halyna Myroniuk, a retired IHRCA curator.

- Halyna Myroniuk, a retired assistant curator for the Immigration History Research Center Archives, speaks at a screening for “Holodomor: Minnesota Memories of Genocide in Ukraine,” at Andersen Library on Tuesday, March 19, 2024. Myroniuk was a research consultant for the film. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

- Daniel Necas, archivist at the Immigration History Research Center Archives, speaks at a screening for “Holodomor: Minnesota Memories of Genocide in Ukraine,” at Andersen Library on Tuesday, March 19, 2024. (Photo/Adria Carpenter)

“The IHRCA was hugely responsible for our success,” she said. “It was very research heavy, and they really made that research possible.”

Similar to working on the oral history project, Gutmanis encountered familiar names and faces in the archives, people she knew as a child. But now as an adult, she could understand and relate to her community on a more profound level.

“I just never thought I would have such an opportunity to research the world that I grew up in,” she said. “There were some really dynamic people that were trying to do serious things. It was a privilege to get to know them better in the archives.”

Following the research phase, Gutmanis wrote and directed the film, partnering with St. Michael’s and St. George’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church, St. Constantine Ukrainian Catholic Church and St. Katherine Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

After a private screening for the film’s supporters last year, Gutmanis is now working through the legal and administrative groundwork for distribution. So far, the reception to the film has been positive.

“It’s a critical time for Ukraine right now, and hopefully the film can help garner support by educating people and making an emotional impact,” Gutmanis said. “Now we just have to figure out the distribution.”